The supply chain woes that began in 2020 because of the pandemic and America’s over-reliance on China for everything from Tylenol to those ubiquitous Covid-era face masks caused prices to spike. Inflation wasn’t pushed higher by China tariffs imposed in 2018. It was caused by record-breaking government spending during the pandemic, and supply chain snafus.

Just how much of the rally in prices came from the logistics crunch? In the case of the US, about 60% since 2021, according to a paper from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco published Tuesday.

International shipping companies also raised rates as demand for online commerce grew during lockdown periods in 2020-21, and China’s “zero Covid” policy which saw factories closed or working only one shift in the mainland. All of this put pressure on inflation, which was under 3% for at least two years following the Section 301 tariffs on some $350 billion worth of China imports.

Since June 2022, shipping bottlenecks have eased. The World Shipping Council, representing container carriers and other operators, said that freight rates are determined by supply and demand and that they were “an element” of inflationary pressure in 2022. This year, though, “this effect has already disappeared,” Bloomberg reported on Wednesday.

Import Dependence and Inflation

The recent global crisis has led to the highest rates of inflation in forty years. Persistent global trade imbalances have given rise to differences in countries’ susceptibility to inflation during supply shock periods due to pandemic or geopolitical hostilities. That is because trade surplus countries are less import-dependent and thus more resistant to supply problems abroad.

For the U.S., the long-running process of offshoring industry and jobs has effectively limited our economy’s ability to reduce supply chain shocks and subsequent higher inflation.

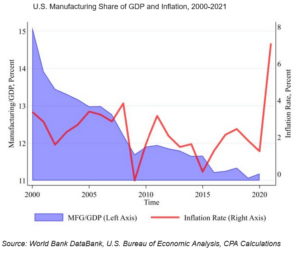

The graphic above shows the relationship between the U.S.’s declining share of manufacturing to GDP (purple) and the average annual rate of consumer price inflation (red).

Free trade and offshoring have resulted in lower prices as the overall trend in inflation has declined since the early 2000’s. The argument for importing from low-wage, low-regulation countries, with the resulting lower sticker prices, seems to work…until it doesn’t. Now facing the highest rate of inflation in decades, we have constrained our ability to mitigate supply shocks because of our decades-long process of offshoring U.S. jobs and, thus, the ability to produce the supplies we need at home rather than compete with the world for the same product all made – more often than not – in one country (China).

The above chart shows the long-running decline of the U.S. manufacturing sector since China entered the World Trade Organization and garnered Most Favored Nation status in 2001. Today, we have reached the lowest share of manufacturing to GDP while simultaneously experiencing the highest rate of inflation.

CPA’s economics team did a study on supply chains and inflation last August. They found that import dependence has been correlated with inflation across time and countries. Many countries that were import-dependent were more vulnerable to global supply shocks and as a result saw inflation spike out of control in 2021. It didn’t matter if the government stimulated the economy or not. Those that experienced the worst inflation during the pandemic were the ones who could not produce the supplies they needed at home.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has argued to remove the Section 301 tariffs against China to help fight inflation.

Those tariffs come under review this fall.

CPA chief economist Jeff Ferry calls the argument that tariffs caused inflation “the dog that didn’t bark.”

Inflation took off later, in 2021, not because of anything to do with tariffs, he said. Inflation is a macroeconomic phenomenon, caused by excessive total demand chasing inadequate total supply. In 2021, the U.S. economy was whacked from both sides, demand and supply. Excessive aggregate demand was generated by too-loose fiscal and monetary policies in late 2020 and early 2021. Restricted supply was caused by the post-pandemic supply chain snafus which began in the fall of 2020, when goods demand suddenly snapped back, surprising manufacturing companies worldwide. In the U.S., excessive concentration on foreign sources of supply that were unwilling and/or unable to increase output intensified the problem. So did the inability of the shipping industry to handle the additional import traffic.

“For sure, the 301 tariffs contributed no measurable effect on inflation,” Ferry said. “It was the supply chain-induced shortages caused by the pandemic that had a much larger effect on inflation.”

Former Treasury Secretary Ben Bernanke, in a working paper published by the Peterson Institute for International Economics, said most of the inflation surge that began in 2021 was the result of sharp increases in commodity prices and sectoral price spikes, resulting from changes in demand together with constraints on supply.

The words “tariff” or “Section 301” did not appear on any of Bernanke’s 41-page explainer on what caused inflation to rise so fast.

“The combination of globalization and financialization led the corporate sector to make the US dependent in many product areas on too few producers located too far away,” said Ferry. “An inflationary surge was almost inevitable in this dangerous situation.”