Press reports say that Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen is arguing for repealing a broad set of U.S. tariffs, allegedly as a way to fight inflation. Her argument is said to rely on a set of reports[1] published in March by the Peterson Institute that claimed that cutting tariffs would cut 1.3 percentage points off the U.S. rate of inflation. U.S. Trade Representative Katherine Tai, on the other hand, dismissed the Peterson study as “something between fiction or an interesting academic exercise.”

A close look at Peterson’s arguments show that Tai is right: Peterson’s work is based on a theoretical model that has little relationship to the real world. The Peterson economists not only use an over-generalized theoretical model; they then introduce even more unrealistic assumptions into the model such as an excessively high elasticity of demand for imports, which generate the results they want, a large and unwarranted inflation reduction from tariffs.

Peterson’s methodology reflects the general tendency of many trade economists to rely on theoretical models and their cousin, computer-driven models, which enable them to avoid looking at real-world data. To make matters worse, they routinely confuse their model results with the real world when claiming results with a wholly artificial scientific precision. The result is to create an Alice-In-Wonderland world where effects inside a theoretical model are transferred to the real world with no recognition that the model produced the results it did because it was designed specifically to produce those results. Trade models have their uses but they also have limitations. They should be used judiciously and always compared with what we observe in the real world.

In the essay that is at the heart of the Peterson (and presumably the Yellen) argument, Peterson economists Sherman Robinson and Karen Thierfelder claim that “tariffs very quickly affect the prices of imported goods in domestic markets, as importers pass on the price changes to consumers.”[2] This is a piece of standard economic theory. But what the real-world evidence shows is that the tariffs imposed by the Trump administration have had strikingly little impact on prices in the U.S. This is in fact the major learning from the Trump tariffs: just how little impact they had on U.S. inflation.

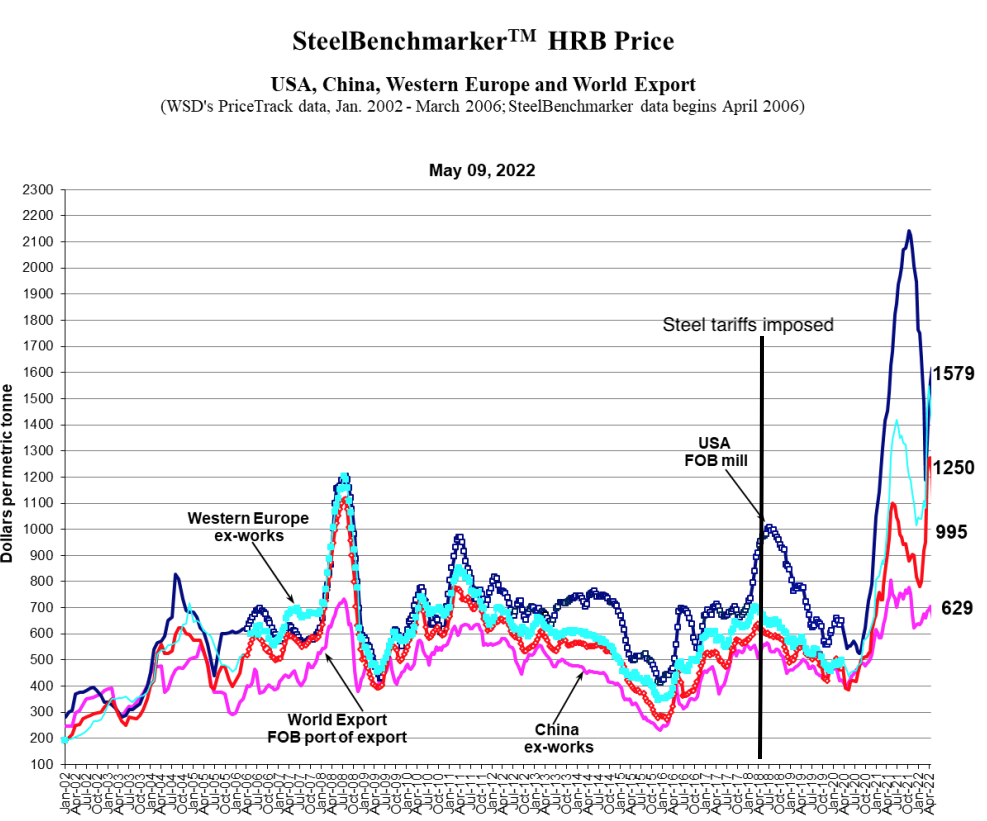

The 2018 steel tariffs are one of the examples discussed in the Peterson articles in a wholly synthetic way. As Figure 1 below shows, U.S. steel prices were not increased by the tariffs. Instead, steel prices ran up before any tariffs were imposed, in late 2017 and early 2018 as steel buyers bought up steel in anticipation of possible shortages. Once the tariffs were announced, steel prices fell. In both 2018 and 2019, average steel prices were BELOW the pre-tariff levels of 2017.

Steel Tariffs and Steel Prices: The Facts

Why were steel prices so low in the wake of the tariffs? The main reason is that steel-using industries were growing strongly and steelmakers, suddenly protected from import pressure, were increasing their output, which reduced their unit costs and prompted them to compete more aggressively. Also, the buildup in stocks at steel service centers before the tariffs arrived was run down after March 2018, putting downward pressure on prices.[3]

In the autumn of 2020, steel prices took off, reaching unprecedented highs. This happened because steelmakers had shut down their furnaces and mills early in the pandemic. All U.S. industry missed the speed and power of the economic resurgence that arrived in the second half of 2020. Then the Russian war on Ukraine impacted the steel market, generating a new bout of worldwide fear of shortages, accelerating stockpiling and raising prices. Today prices are subsiding once again.

All these gyrations make it clear that tariffs have no measurable impact on steel prices, U.S. or worldwide. A series of powerful supply and demand shocks have consistently overwhelmed any impact of tariffs.

Figure 1. Steel Prices 2002-2022

Source: Steelbenchmarker

U.S. Tariffs and Consumer Price Inflation

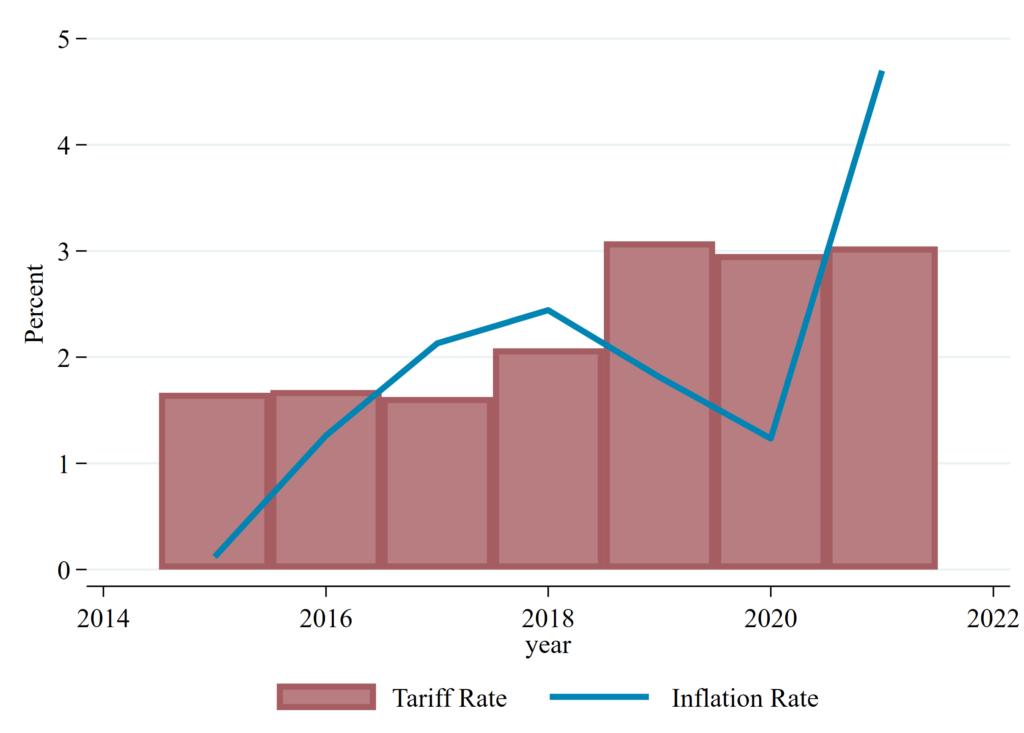

Steel is far from a lone example. Another instructive case is the U.S. economy as a whole. Peterson and other globalist economists bemoan the 2018-2019 tariff increases as shocking and unprecedented. In a sense they are right. The U.S. had not seen such tariff increases as we saw in 2018-2019 in 88 years. So what was the overall impact of these “shocking” tariffs on U.S. inflation?

Figure 2 tells the story. The red bars show the average effective tariff rate in the U.S. In 2019 the U.S. saw what some would call a “huge” increase in tariff levels. In that year, customs duties shot up by 46% to $77.8 billion, according to Bureau of Economic Analysis data. The actual tariff rate, calculated as total duties revenue divided by total goods imports, rose from 2.08% to 3.09%. This is a huge increase in relative terms.

What happened to inflation? Inflation actually fell in 2019, as measured by the Consumer Price Index (blue line in Figure 2). Wait a minute! I thought Peterson said tariff changes “very quickly” affect prices!?! Well yes, they did say that. But they were referring to their models. Not to the real world.

Inflation took off later, in 2021, not because of anything to do with tariffs. Inflation is a macroeconomic phenomenon, caused by excessive total demand chasing inadequate total supply. In 2021, the U.S. economy was whacked from both sides, demand and supply. Excessive aggregate demand was generated by too-loose fiscal and monetary policies in late 2020 and early 2021. Restricted supply was caused by the post-pandemic supply chain snafus which began in the fall of 2020, when goods demand suddenly snapped back, surprising manufacturing companies worldwide. In the U.S., excessive concentration on foreign sources of supply that were unwilling and/or unable to increase output intensified the problem. So did the inability of the shipping industry to handle the additional import traffic.

The Peterson economists mostly agree with this analysis of inflation, pointing out, accurately, that inflation is “a dynamic process with aggregate demand exceeding supply over an extended period.”[4] In this paragraph, they tiptoe up to the precipice of saying “well actually tariffs have nothing to do with inflation.” They look over the edge, take fright and run back to clutch at the fictions of their computer-generated equilibrium models the way old ladies clutch at their pearls.

Figure 2: U.S. Average Tariff Rate vs. U.S. Consumer Price Inflation

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Bureau of Labor Statistics, CPA calculations.

Smoot-Hawley and Inflation in the 1930s

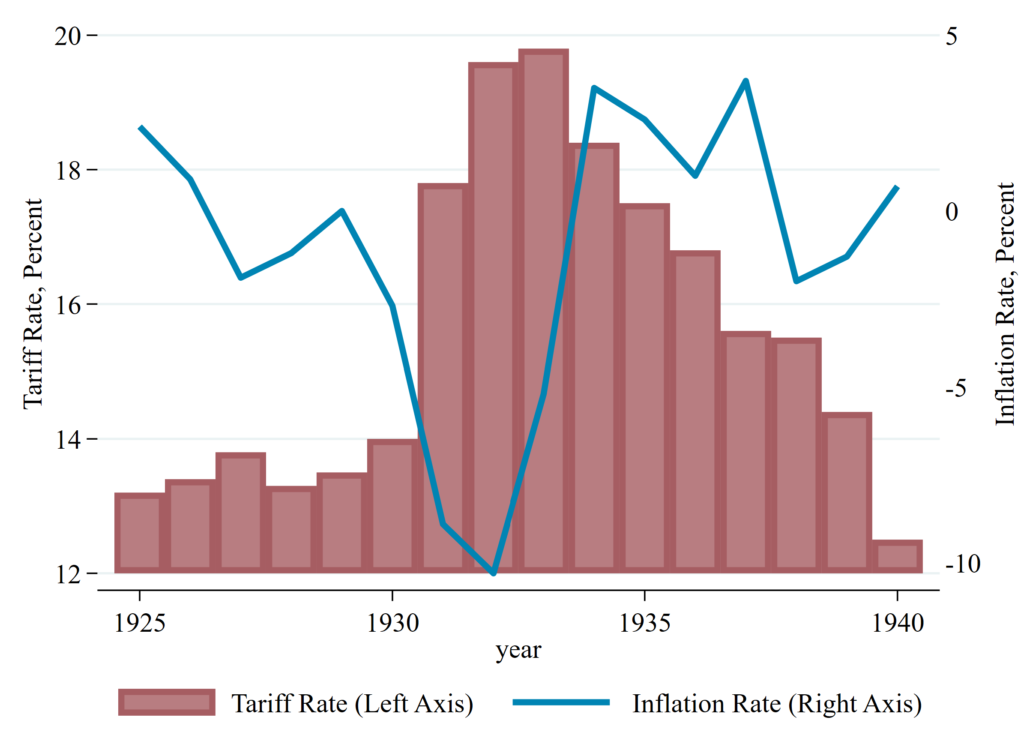

Let’s take one more quick look at tariffs and prices before we focus on the details of the Peterson model. As our friends at Peterson often point out, the Smoot-Hawley Act of 1930 was the epitome of U.S. tariff raising, at least in the 20th century. Figure 3 shows the impact of Smoot-Hawley: in 1931 tariffs as a share of imports jumped by four points. In 1932, they rose another two points. What happened to inflation? In 1931, prices actually fell by 8.9%. In 1932, they fell by a further 10.3%. Figure 3 appears to suggest that raising tariffs actually lowers prices!

In reality, of course, the Smoot-Hawley tariffs did not raise or lower prices. Any effect they may have had on prices was completely overwhelmed by the forces driving the Great Depression across the world and depressing commodity prices worldwide and with them retail prices. But the example shows yet again that in the real world where so many economic forces play out at the same time, tariffs often have zero effect on prices.

To borrow a phrase from Sherlock Holmes, when tariffs go up, inflation is the dog that does not bark.

Figure 3. U.S. Tariffs and Consumer Price Inflation 1925-1940

Source: U.S. International Trade Commission, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis.

Inflation in Trade Models

What, then, explains the ability of the Peterson model to find 1.3 percentage points of inflation reduction in the abolition of a broad set of tariffs? Simply, the fact that their computer-generated model assumes that tariffs are always passed onto consumers and therefore tariff reductions will be passed on as price reductions. As we explained above, the tariffs imposed in 2018 and 2019 were NOT fully passed onto consumers and in many cases NOT PASSED ON AT ALL. This suggests that abolishing those tariffs would have little or no effect on prices.

Economic theory does show a relationship between tariffs and prices. As explained here by my colleague Amanda Mayoral, theory suggests that normally only a part of tariff increases would be borne by U.S. importers or consumers. However, the real-world evidence from 2018 and 2019 suggests the part that was paid by U.S. companies or individuals was very small and did not impact inflation, which did not increase significantly until early 2021.

The Peterson “GLOBE” Model

None of these real-world observations are incorporated in the computer model used by Peterson, which is a variation of the well-known GTAP model known as GLOBE.

But the Peterson economists go even further in distorting their model to misrepresent reality. In a methodological appendix to their article[5], Robinson and Thierfelder state that they have chosen an elasticity of substitution of five. This important parameter, also known as an Armington elasticity, influences by how much a price or tariff reduction of imports will affect domestic purchases of goods. According to recent trade model research[6], those elasticities are typically between 1 and 3. Robinson and Thierfelder offer no explanation for their choice of a substantially higher elasticity. Their elasticity parameter exaggerates the anti-inflationary impact of a tariff cut. Presumably, Robinson and Thierfelder assume that the political forces that make use of their model’s conclusions will not delve much into the assumptions and parameters behind those results.

In our own modeling work, we tend to choose small elasticity levels and attempt to validate them with real-world evidence or observations. Other trade economists do the same.

Additionally, Robinson and Thierfelder explain that their model builds in a rise in prices due to what they call a “general equilibrium effect” by which a rise in import prices leads to a rise in prices of non-traded goods. We are here definitely in the realm of “If pigs could fly, you could have ham and eggs on the wing.” In other words, they are piling assumption on top of assumption to ensure they get large results. The most egregious assumption contained in this section of their analysis is that the trade deficit must remain constant. As pretty much all economists agree, the U.S. trade deficit does not remain constant over time and certainly not recently. We have seen it expand dramatically in 2022. They explain that they make this assumption not because a constant trade deficit has been observed in the real world but because it is the traditional assumption made in economic theory. It is an unrealistic assumption for the U.S. and it contributes to the unrealistic results.

Likely Impacts of Large-Scale Tariff Cuts

Finally, what do we think would happen if tariffs were cut in the form recommended by Peterson, i.e. by abolishing the current tariffs on steel and aluminum, abolishing all Section 301 tariffs on China, repealing all anti-dumping/countervailing duty tariffs, and abolishing all Buy American proposals.

Our view is that this would cost the U.S. hundreds of thousands of jobs very quickly, it would lead to a sizeable increase in import penetration in many industries, it would embolden and empower China to further decimate U.S. industries ranging from microchips to solar panels to steel, machinery and automobiles…and it would have zero impact on inflation.

Inflation is a macroeconomic phenomenon. There are two main ways to address it. The first is with macroeconomic policies, namely fiscal and monetary policy. To its credit, the Biden administration is already doing that. In the first four months of 2022, the federal government actually ran a small surplus, of $18 billion (contrasting with the federal budget deficit of $2.78 trillion in the whole of fiscal 2021) and monetary policy is tightening with recent interest rate increases and expectations of more half-point federal funds rate increases to come.

The other major contributors to inflation are the supply shortages, bottlenecks, and snafus. Here the administration is not doing enough. It could take more aggressive action to launch alternative sources of supply in bottlenecked industries such as pharmaceuticals or semiconductors or baby food. The alternative sources of supply should be located in the U.S., to contribute to U.S. jobs and economic growth, and to avoid the persistent shipping and port bottlenecks.

Admittedly, such investments in U.S. manufacturing capability would be unlikely to impact inflation rates this year. But such actions would send signals to the multinationals that have made supply unreliable and un-resilient that Americans have an interest in reliable and diverse supply based here at home.

Footnotes:

[1] See: Hufbauer, Gary Clyde, Hogan, Megan, and Wang, Yilin, For Inflation Relief, the US Should Look to Trade Liberalization, March 2022, Peterson Institute of International Economics, March 2022. Available here.

[2] Robinson, Sherman and Thierfelder, Karen, Can liberalizing trade reduce US CPI inflation? Insights from an economywide analysis, PIIE, March 2022. Available here.

[3] (Warning: Wonky footnote on economic theory.) There is much confusion in public commentary about the impact of tariffs on prices and what economic theory says about what their impact is expected to be. As my colleague Amanda Mayoral has written in an article on optimal tariff levels, economic theory shows that the cost of a tariff will almost always be split between the seller of the good (the exporter) and the buyer (importer). In the case of the U.S., theory suggests the size of the U.S. market would mean the U.S. importer would pay a relatively smaller share of the tariff than the exporter, who would likely pay the majority of the burden. However, economic theory refers to the long term in which prices are determined by including all costs, with an allowance for a profit margin on top. Economic theory never specifies how long the long term is expected to be, but if pressed most economists would offer a guesstimate of between two and ten years. In the real world, prices, especially in volatile commodities like steel, move on a daily basis and respond primarily not to long-term costs but to short-term business opportunities. Steel prices fell after the tariffs were imposed because the new competitive situation (the 30% of the market that had been imports was now handicapped by tariffs) stimulated the half-dozen major U.S.-based steel producers to invest in greater capacity and aggressively seek more market share. This induced them to cut prices despite the tariff. This sort of industrial economic analysis is intentionally excluded from trade economics, because if it were included, the result would be to have very different and hard-to-predict results for each industry and it would be impossible for a comprehensive economy-wide trade model to produce meaningful forecasts.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Robinson, Sherman and Thierfelder, Karen, Appendix: Methodology for “Can liberalizing trade reduce the US consumer price index?” Available here.

[6] Saad, Ahmad, Montgomery, Chris, and Schreiber, Samantha, A Comparison of Armington Elasticity Estimates in the Trade Literature, Conference paper, 2020. Available here.