You might not believe this, but McKinsey & Company just made the case for reshoring.

On April 15, the McKinsey Global Institute published a shocker of a masterpiece on American manufacturing. “Shocking” because one would never imagine it to have come from one of the premier Davos-minded business consulting firms in the world. For years, firms like McKinsey have touted open and free markets, big corporate power, and moving supply chains as far away from the U.S. as possible to scale up in Asia where labor was abundant, and all sorts of regulations were not.

From McKinsey:

“The United States is facing something of a now-or-never moment to regain capabilities and market share. There is also a growing sense that its frayed social fabric will not be repaired without more middle-class jobs and attention to the places that have been left behind.”

Their discussion paper maps out how to do an about-face from current globalization trends. It’s a must-read for any policymaker concerned with reindustrializing this country.

The report hits on many of the issues advocated by the Coalition for a Prosperous America, from reshoring critical supply chains among certain sectors of the economy, to highlighting environmental and climate risks in Asia and other markets. They’ve caught on to the Biden administration’s lingo and are using its words to promote a manufacturing-led economic renaissance in the U.S., calling the sector “critical for inclusive growth” as many jobs in manufacturing are in blue-collar communities far from the tech and finance hubs in large cities.

Employees of Zekelman Industries’ Wheatland Tube in small-town Pennsylvania. A lot of their business has been saved by national security policies from Washington, including tariffs.

“Learn to Code”

Manufacturing accounts for $2.3 trillion of GDP and employs 12 million people. It is the main economic activity in hundreds of counties. The sector represents roughly 10% of GDP and jobs, but it accounts for at least 20% of the nation’s capital investment, 30% of productivity growth, 60% of our exports, and 70% of business spending on the research and development that keeps us innovating. It is, as McKinsey Global Institute admits, “the main economic engine and primary employer in some 500 counties across the nation.”

Some might call it fly-over country. We think of them as the middle-class hubs of American life. In some cases, they are “former” middle-class hubs of American life; decimated over the years thanks to a China-centric globalization model promoted by the Davos Universe – global corporations and investment firms.

Some who have promoted that model now see its negative impact on society and the job market at large, as Gordon Hanson of the Harvard Kennedy School writes in a recent Foreign Affairs article.

For those out there who don’t want a job at Target, a nursing home, or “learn to code”, making things is the best option for economic stability and financial security. Manufacturing jobs tend to be full-time with benefits and opportunities for advancement and retraining. They also support small and mid-sized enterprises (SME) that serve the supply chain needs of large multinationals. Many of them are family-owned, with generations working in the same factory for years, strengthening community life in small towns.

Without those business relationships, the big contractors – whether Walmart or General Motors – will increasingly look elsewhere in the world for the same, or similar product, further shrinking American manufacturing. This erodes societal cohesion in the communities that depend on these businesses, not to mention reduces tax revenues that fund schools and other public goods. These areas then become more dependent on the state and federal government to function.

The entrance of China into the World Trade Organization in 2001 propelled the offshoring of manufacturing. The trade deficit in manufacturing fell during the Great Recession in 2008. Now it’s back, with no end in sight. Even McKinsey thinks this is bad news.

McKinsey notes, as we do, that manufacturing is “critical for national security and resilience.” Having a weak industrial base leads to overreliance on imports – as we have learned from this pandemic on the medical side, and most recently with semiconductors used in the automotive industry that are hyper-reliant on Taiwan Semiconductor.

Despite the newfound love for China as the go-to consumer market (after years of being the go-to manufacturing center), McKinsey points out that the U.S. market is also an asset to any company. The consumers are here, too.

The U.S. manufacturing sector has been through a rocky period. But the advantages of cheap finance, a massive labor pool, and a huge home market, are “formidable and could form the basis for a new wave of growth,” report authors wrote.

From outsourcing pollution to an overvalued dollar, here’s where McKinsey and CPA see eye-to-eye.

The Overvalued Dollar

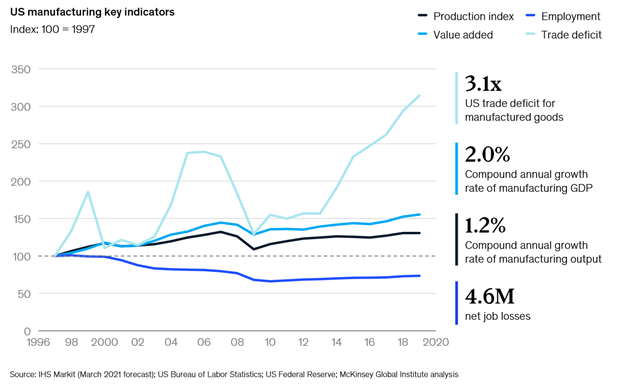

If the economy is going to be globalized, then any change in relative costs or demand versus the world can result in plant shutdowns and layoffs. The United States has been through a sequence of those events in recent decades, with downtrends beginning in 1997 due to the sharp appreciation of the dollar, McKinsey said.

Looked at over a longer, more recent period, between 2003 and 2016, “the dollar remained 20% to 25% higher than where it was in the mid-1990s versus the euro, South Korean won, and Sweden’s krona. It also averaged 30% higher than its 1995 level against a basket of Southeast Asian currencies, and 45% to 55% higher against the Taiwanese dollar and Japanese yen,” McKinsey states.

These are all countries with persistent long-term trade surpluses with the United States.

Here is what is happening to U.S. manufacturing as a result of currency misalignment and China-centric globalization. To please Walmart and Goldman Sachs, the U.S. economy is a China jobs program.

From McKinsey:

“A strong dollar does help U.S. importers and consumers, and it can also help U.S. manufacturers acquire assets and raw materials overseas. But an overvalued dollar can take a toll on domestic manufacturers’ market share and profit share at home and abroad. Even small differences in currency valuations, compliance costs, and input costs can have a magnified effect. An overvalued dollar can mean an effective price discount of 10% to 15% for the low-margin import competition.”

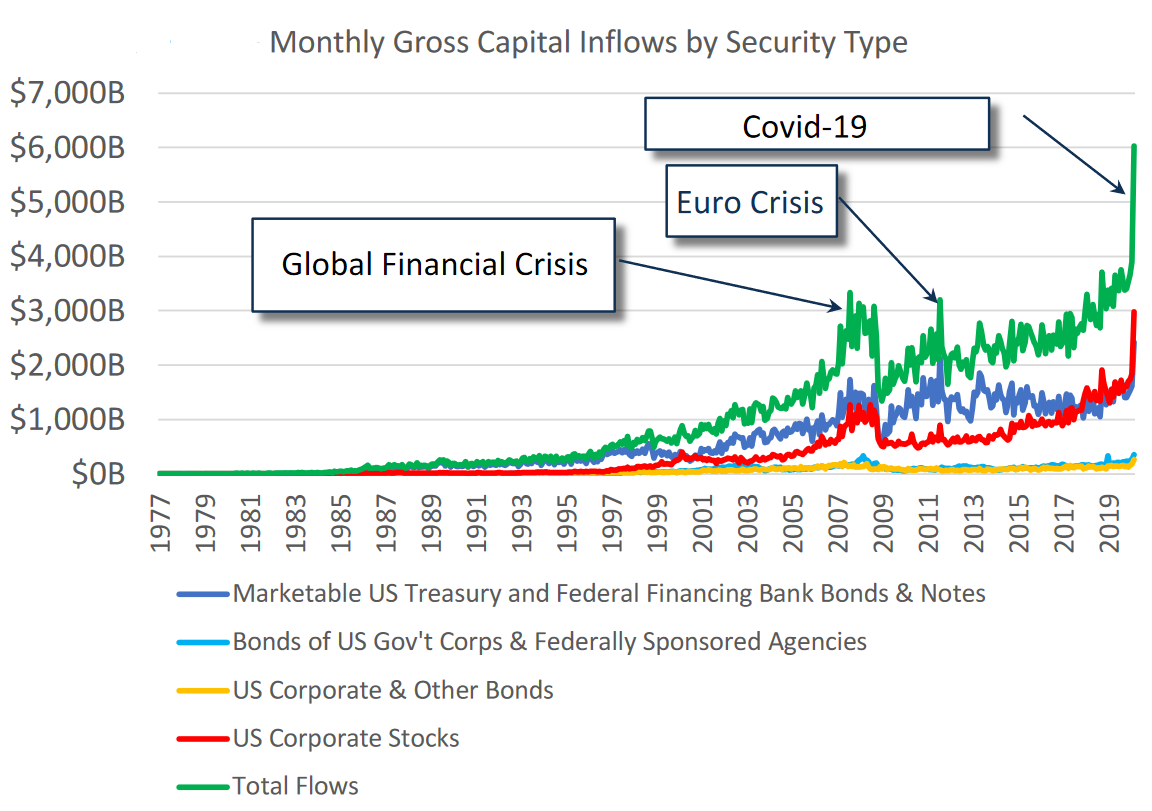

In September, CPA’s Jeff Ferry spearheaded a working paper on how a Market Access Charge (MAC) on international capital inflows into the U.S. securities market would impact the economy.

We built a model including the relationships between U.S. capital flows, the dollar exchange rate, U.S. trade, and the U.S. domestic economy and our conclusion was that a 5% MAC on foreign portfolio investment would realign the dollar to a current account balancing exchange rate, balance trade and stimulate the U.S. economy. A 5% tax on securities purchases by offshore hedge funds and foreign institutional investors would generate an additional $1 trillion of GDP, over 4 million additional jobs, and more than $300 billion in additional revenue for the U.S. Treasury.

The chart below shows why the dollar is so strong against other currencies on a trade-weighted basis: foreign investor demand for America’s number one product — stocks and bonds.

Legislation to realign the dollar has already been drafted. Last year, Senators Tammy Baldwin (D-WI) and Josh Hawley (R-MO) introduced a bipartisan bill that would impose the Market Access Charge on foreign purchases of U.S. securities. Doing so would address the glut of foreign investment that keeps driving up the dollar and making it almost impossible for domestic manufacturing to compete globally on wages and input costs alone.

Most middle supply chain companies in the tooling and metals fabrication segment of the economy will never win a bid if their large corporate customer is opening the bid to companies from weak currency rivals.

Currency misalignment is a big impediment to reindustrialization. CPA is discussing the MAC with people inside the Treasury Department.

The currency story remains a hot one in Washington, with Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen recently opting to free Vietnam of a currency manipulator warning put in place by the previous government. Vietnam’s currency is practically worthless. And it has become an outpost of Chinese multinationals offshoring to avoid tariffs. All of this is great for Vietnam, but not so great for Americans who, in an Asia-centered supply chain, are competing with workers who make between $7,000 and $17,500 annually to make kitchen cabinets and apparel on sale at Macy’s made from Chinese textiles.

Equity and Race

Equity and Race

Equity and racial inclusion in economic progress are at the fore of the new Biden administration. Manufacturing, from Detroit auto workers to North Carolina yarn mills, hire a lot of minority workers, surely more than Silicon Valley does, based on data by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

Job losses in manufacturing hurt minorities most. Blacks are roughly 13% of the U.S. population, with Hispanic/Latinos around 18%. They are underrepresented overall in both durable and non-durable goods manufacturing, according to BLS data.

Within subsectors of manufacturing, Blacks are over-represented as a portion of their population size in automotive manufacturing (18.2%) and in fabric mills (16%), both highly globalized industries. When these sectors lay off and offshore, this community is heavily impacted.

The erosion of manufacturing in favor of cheaper, foreign-sourced goods has undermined their ability to rise into, and stay in, the middle class, McKinsey authors wrote. The United States meets just 71% of its final demand with domestic goods, a smaller share than in Germany, Japan, or China. We import the rest. As a result of that, the United States has lost some 5.8 million manufacturing jobs between 1999 to 2009.

Starting in 2010, the U.S. saw a return to modest employment growth with the addition of 1.3 million jobs after the 2008-09 financial crisis. The pandemic led to another setback, erasing roughly 500,000 jobs, McKinsey estimated.

CPA is working on a new Job Quality Index (JQI) based on race and gender. A preliminary look shows that Blacks and Latinos are represented heavily in low-quality, low-wage jobs.

Latinos are heavily present in the hospitality and leisure sectors (24.1%), with Blacks being over-represented as a percentage of their population in public transportation (18.7%), government office jobs (17.5%), and education and healthcare services (14.8%).

One of the reasons why Black and Hispanic workers are at the bottom of our new JQI chart is due to their heavier weighting in low-paying service sector jobs. If we had more blue-collar manufacturing jobs, we are convinced that this chart would improve. One just has to look at the history of Detroit during the heyday of the automotive industry to see the economic and cultural benefits manufacturing booms can bring.

The tens of thousands of jobs lost in the auto sector over the last 10 years, and the plight of classic automotive hubs in Michigan, should serve as a good case study as to what the exodus of skilled manufacturing labor means to racial equity in the nation’s job market.

Save the Planet? Not with ‘Global Pollution Chains’

We like to call the focus on transoceanic shipping for everything from steel rebar to solar panels as being part of the global pollution chain. In many cases, we are outsourcing pollution.

By preparing to go green in the U.S. to prevent climate change, policymakers are inadvertently pushing companies to offshore their pollution to less environmentally rigorous countries. This hurts domestic companies that cannot compete with their rivals’ weaker regulations.

From McKinsey:

“Meeting bolder sustainability goals requires confronting the environmental costs of importing goods from halfway around the world, particularly if they are made in places with looser standards for industrial pollution and emissions than the United States.”

On April 21, Biden announced plans to cut CO2 emissions. This is good news for solar and wind. But where will our windmills and solar panels come from?

China wind turbine giant Goldwind has seen its installations in the U.S. go from just 2 in 2019 to 48 in 2020, according to the Global Wind Energy Council. Europe is our lead supplier, with GE Renewables making wind turbine blades in North Dakota. Their Rhode Island offshore wind project’s main parts – the turbine and blades — were mostly imported from France, where GE Renewables is headquartered.

China dominates this solar supply chain and CPA estimates that it accounts for more than 80% of the solar panels imported in the U.S. Some of the polysilicon that goes into making solar cells comes from Xinjiang, a region now infamously known as the home of large-scale detention centers for Uyghur Muslims.

Beyond solar and wind, if the U.S. is going to cut back on its CO2 emissions by outsourcing pollution to other countries, it’s like recycling plastics here only to watch them pile up in a landfill in India. It would be better if we recycled them here, for example, and created an industry to do it. It would be better if government wind-powered utility contracts required blades and turbines to be made here. The same with solar-powered utilities. If someone wants to put imported solar panels on their roof, that is their prerogative. But state and local governments need to support supply chains here. If not, America’s climate change policy will be yet another Asian jobs program.

“We need job and renewable production targets to go with these reduction plans,” says Michael Stumo, CEO of CPA. “Emissions targets are not enough as lowering these could either be job creators or job and industry, killers.”

CPA sent a letter to USTR Katherine Tai on April 22 to let her know that lowering emissions needs to be wedded to job creation, and not just in the American sales departments of companies installing Chinese solar panels.

CPA supports President Biden’s Executive Order expanding “Buy American” policies and the goals of the new “American Jobs Plan,” including the proposal to convert the federal vehicle fleet to American-made electric vehicles.

However, China dominates electric vehicle (EV) production now due to its massive domestic market, and U.S. automakers are moving electric vehicle production to other countries, such as Ford’s new Mustang Mach-E, made in Mexico. CPA’s automotive supply chain members are seeing their orders from automakers dwindle rather than shift to EV production. We have three new pure-play EV domestic car companies outside of Tesla.

Environmental advocates often promise that their policies will create millions of green jobs for U.S. workers. Unfortunately, when it is time to implement programs to achieve those goals, the environmental objectives often predominate while the jobs objectives are aspirational, CPA told Tai in its letter last week.

U.S. Semiconductors: A Collapsing Model

Like McKinsey said, the nation is facing what may be a “now-or-never moment” to inject new life into its industrial base. Semiconductors are a prime example of that.

We design them, but Samsung and Taiwan Semiconductor (TSMC) mostly make them. Our industry has taken on what is known as a “fabless” model, where the design, equipment, and IP are what matters. Manufacturing the actual chips to scale is mostly an afterthought.

That’s changing. But McKinsey warns that the remedy cannot come from grants, funding for R&D, retraining, and tax cuts alone. There needs to be a clearly articulated goal and a road map for achieving those goals so the U.S. is making, not just designing, microchips.

From McKinsey:

“It can take $20 billion to build a new fab that produces next-generation five-nanometer chips—and the cost can double every two to four years in succeeding product generations. It can take three years of low utilization and yield to ramp up. Few U.S. investors will accept such a long horizon. Companies could simply build smaller fabs with lower up-front costs, but they risk losing economies of scale. TSMC’s most recent five-nanometer fab in Taiwan, for example, has about four times more capacity than its planned Arizona facility for a cost estimated to be only 48% greater. The U.S. semiconductor industry faces another competitive hurdle when it comes to investment. In addition to the fact that foreign competitors have already achieved economies of scale with large and well-established ecosystems, some are also backed by substantial public subsidies…which can account for up to 70% of the cost differential between a U.S. leading-edge fab and one based in mainland China, Taiwan, or South Korea.”

CPA published a white paper on semiconductors in March.

For starters, we argue that the U.S. must respond to this collapsing fabless model by strengthening the enforcement of the 2018 Export Control and Reform Act. Semiconductor equipment makers and electronic design automation tool companies must be prevented from selling to entities with Chinese military ties. Today, that enforcement is too weak.

We think the U.S. government needs to implement reforms to support a substantial increase in chip manufacturing with a goal of producing 50% of semiconductors in every major category from logistics to analog. This will strengthen U.S. national security and diversify supply and resiliency. Just as important, we think it will create hundreds of thousands of high-paying manufacturing jobs in the U.S.

The 16 ‘National Champions’: A Necessary Remapping

Supply-chain disruptions have become more frequent and more severe in recent years. The risks are only growing more pronounced in light of climate change, cyberattacks, pandemics, geopolitical uncertainty, and trade disputes. Resilience enables an economy to withstand various types of supply-chain shocks with minimal impact on public welfare and the operations of related industries that depend on key inputs, the McKinsey report states.

For McKinsey, if the U.S. had a “national champions” sectoral model, like China, the following 16 sectors would be the most vital due to their relevance to national security and their importance to overall supply chain resiliency.

Basic metals; autos and auto parts; fabricated metals; specialty chemicals; petrochemicals; general machinery/tooling; special purpose machines; electrical equipment and electronics; medical devices; semiconductors; communications equipment; precision tools; pharmaceuticals; transportation equipment; aircraft and defense equipment.

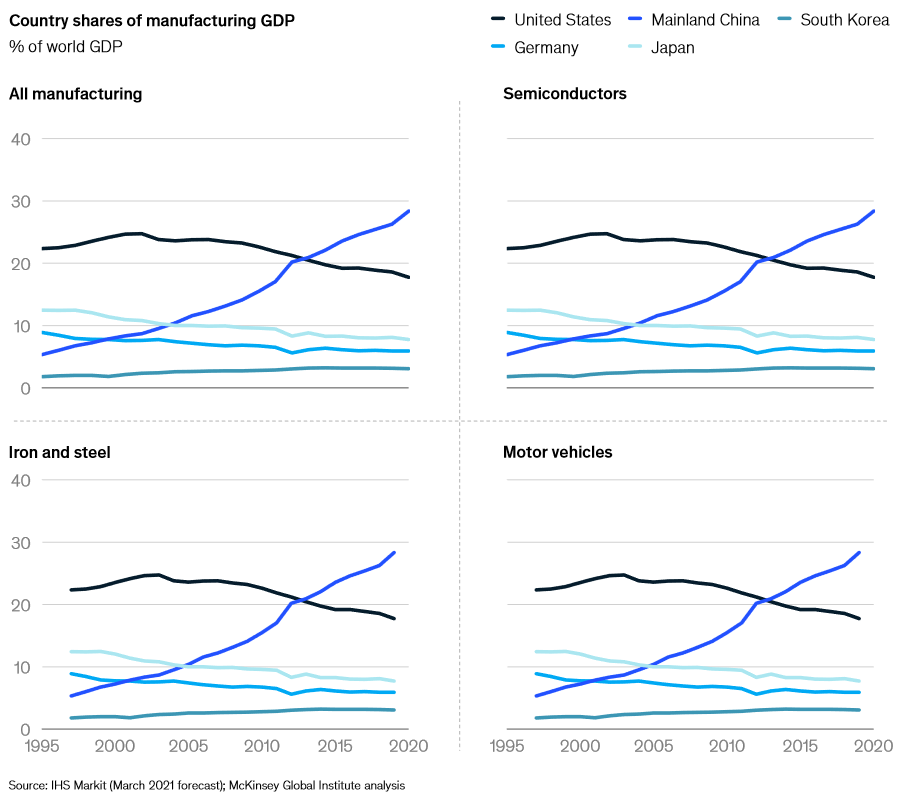

From 1995 to 2019, the U.S. share of global manufacturing GDP dropped by an average of 6 percentage points across these 16 industries. As a result, the gross trade deficit grew by 7.5 percentage points, according to McKinsey.

From 1997 to 2016, foreign sourcing of the intermediate parts used in domestic car manufacturing rose from 10% to 15%. These trends, which were mirrored in other industries (and other advanced economies), either squeezed smaller suppliers out altogether or forced them into relentless price competition, McKinsey noted. In 2017, they analyzed firm-level financial results going back to 1990 and found that manufacturers with more than $1 billion in assets saw revenues grow by more than 2% annually. These are the globalist corporations, sourcing their wares from Asia (and selling there, as well).

At the same time, small and medium-size manufacturers posted negative growth.

These data points should drive home a clear message: the ability to make things domestically matters.

Industry leaders, policymakers, and the public alike have gained a fresh resolve to make the United States better prepared and more self-sufficient as the pandemic showed our weaknesses.

Port-side congestion today, with empty containers going to China in order to ship Made in China goods asap to the U.S., means that a lot of our post-pandemic recovery and stimulus checks are going to Asian sourced goods.

In February, the Biden administration ordered an immediate review of vulnerabilities in the nation’s supply chains. But Trump had done something similar. There are numerous bills in Congress that will address these issues. We need action on them, not endless reviews and investigations. We know what we are up against, from an overvalued dollar to China’s economies of scale backed by failsafe state subsidies.

Some in government are averse to China-like subsidies and picking favorite industries. If that’s not the chosen track to take, then something will need to be done with the dollar (like our MAC charge), or tariff protections on those 16 sectors highlighted by McKinsey.

If the United States manufacturer, and the workers that support it, are going to be forced to run a three-legged race in a potato sack, then they will increasingly need government to send someone onto the tracks for help. Preferably with tripwire against those running freer, with a mighty wind at their backs.

From Climate to China Dependency, Remapping Supply Chains Gains Traction Among Big Business

You might not believe this, but McKinsey & Company just made the case for reshoring.

On April 15, the McKinsey Global Institute published a shocker of a masterpiece on American manufacturing. “Shocking” because one would never imagine it to have come from one of the premier Davos-minded business consulting firms in the world. For years, firms like McKinsey have touted open and free markets, big corporate power, and moving supply chains as far away from the U.S. as possible to scale up in Asia where labor was abundant, and all sorts of regulations were not.

From McKinsey:

Their discussion paper maps out how to do an about-face from current globalization trends. It’s a must-read for any policymaker concerned with reindustrializing this country.

The report hits on many of the issues advocated by the Coalition for a Prosperous America, from reshoring critical supply chains among certain sectors of the economy, to highlighting environmental and climate risks in Asia and other markets. They’ve caught on to the Biden administration’s lingo and are using its words to promote a manufacturing-led economic renaissance in the U.S., calling the sector “critical for inclusive growth” as many jobs in manufacturing are in blue-collar communities far from the tech and finance hubs in large cities.

Employees of Zekelman Industries’ Wheatland Tube in small-town Pennsylvania. A lot of their business has been saved by national security policies from Washington, including tariffs.

“Learn to Code”

Manufacturing accounts for $2.3 trillion of GDP and employs 12 million people. It is the main economic activity in hundreds of counties. The sector represents roughly 10% of GDP and jobs, but it accounts for at least 20% of the nation’s capital investment, 30% of productivity growth, 60% of our exports, and 70% of business spending on the research and development that keeps us innovating. It is, as McKinsey Global Institute admits, “the main economic engine and primary employer in some 500 counties across the nation.”

Some might call it fly-over country. We think of them as the middle-class hubs of American life. In some cases, they are “former” middle-class hubs of American life; decimated over the years thanks to a China-centric globalization model promoted by the Davos Universe – global corporations and investment firms.

Some who have promoted that model now see its negative impact on society and the job market at large, as Gordon Hanson of the Harvard Kennedy School writes in a recent Foreign Affairs article.

For those out there who don’t want a job at Target, a nursing home, or “learn to code”, making things is the best option for economic stability and financial security. Manufacturing jobs tend to be full-time with benefits and opportunities for advancement and retraining. They also support small and mid-sized enterprises (SME) that serve the supply chain needs of large multinationals. Many of them are family-owned, with generations working in the same factory for years, strengthening community life in small towns.

Without those business relationships, the big contractors – whether Walmart or General Motors – will increasingly look elsewhere in the world for the same, or similar product, further shrinking American manufacturing. This erodes societal cohesion in the communities that depend on these businesses, not to mention reduces tax revenues that fund schools and other public goods. These areas then become more dependent on the state and federal government to function.

The entrance of China into the World Trade Organization in 2001 propelled the offshoring of manufacturing. The trade deficit in manufacturing fell during the Great Recession in 2008. Now it’s back, with no end in sight. Even McKinsey thinks this is bad news.

McKinsey notes, as we do, that manufacturing is “critical for national security and resilience.” Having a weak industrial base leads to overreliance on imports – as we have learned from this pandemic on the medical side, and most recently with semiconductors used in the automotive industry that are hyper-reliant on Taiwan Semiconductor.

Despite the newfound love for China as the go-to consumer market (after years of being the go-to manufacturing center), McKinsey points out that the U.S. market is also an asset to any company. The consumers are here, too.

The U.S. manufacturing sector has been through a rocky period. But the advantages of cheap finance, a massive labor pool, and a huge home market, are “formidable and could form the basis for a new wave of growth,” report authors wrote.

From outsourcing pollution to an overvalued dollar, here’s where McKinsey and CPA see eye-to-eye.

The Overvalued Dollar

If the economy is going to be globalized, then any change in relative costs or demand versus the world can result in plant shutdowns and layoffs. The United States has been through a sequence of those events in recent decades, with downtrends beginning in 1997 due to the sharp appreciation of the dollar, McKinsey said.

Looked at over a longer, more recent period, between 2003 and 2016, “the dollar remained 20% to 25% higher than where it was in the mid-1990s versus the euro, South Korean won, and Sweden’s krona. It also averaged 30% higher than its 1995 level against a basket of Southeast Asian currencies, and 45% to 55% higher against the Taiwanese dollar and Japanese yen,” McKinsey states.

These are all countries with persistent long-term trade surpluses with the United States.

Here is what is happening to U.S. manufacturing as a result of currency misalignment and China-centric globalization. To please Walmart and Goldman Sachs, the U.S. economy is a China jobs program.

From McKinsey:

In September, CPA’s Jeff Ferry spearheaded a working paper on how a Market Access Charge (MAC) on international capital inflows into the U.S. securities market would impact the economy.

We built a model including the relationships between U.S. capital flows, the dollar exchange rate, U.S. trade, and the U.S. domestic economy and our conclusion was that a 5% MAC on foreign portfolio investment would realign the dollar to a current account balancing exchange rate, balance trade and stimulate the U.S. economy. A 5% tax on securities purchases by offshore hedge funds and foreign institutional investors would generate an additional $1 trillion of GDP, over 4 million additional jobs, and more than $300 billion in additional revenue for the U.S. Treasury.

The chart below shows why the dollar is so strong against other currencies on a trade-weighted basis: foreign investor demand for America’s number one product — stocks and bonds.

Legislation to realign the dollar has already been drafted. Last year, Senators Tammy Baldwin (D-WI) and Josh Hawley (R-MO) introduced a bipartisan bill that would impose the Market Access Charge on foreign purchases of U.S. securities. Doing so would address the glut of foreign investment that keeps driving up the dollar and making it almost impossible for domestic manufacturing to compete globally on wages and input costs alone.

Most middle supply chain companies in the tooling and metals fabrication segment of the economy will never win a bid if their large corporate customer is opening the bid to companies from weak currency rivals.

Currency misalignment is a big impediment to reindustrialization. CPA is discussing the MAC with people inside the Treasury Department.

The currency story remains a hot one in Washington, with Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen recently opting to free Vietnam of a currency manipulator warning put in place by the previous government. Vietnam’s currency is practically worthless. And it has become an outpost of Chinese multinationals offshoring to avoid tariffs. All of this is great for Vietnam, but not so great for Americans who, in an Asia-centered supply chain, are competing with workers who make between $7,000 and $17,500 annually to make kitchen cabinets and apparel on sale at Macy’s made from Chinese textiles.

Equity and racial inclusion in economic progress are at the fore of the new Biden administration. Manufacturing, from Detroit auto workers to North Carolina yarn mills, hire a lot of minority workers, surely more than Silicon Valley does, based on data by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

Job losses in manufacturing hurt minorities most. Blacks are roughly 13% of the U.S. population, with Hispanic/Latinos around 18%. They are underrepresented overall in both durable and non-durable goods manufacturing, according to BLS data.

Within subsectors of manufacturing, Blacks are over-represented as a portion of their population size in automotive manufacturing (18.2%) and in fabric mills (16%), both highly globalized industries. When these sectors lay off and offshore, this community is heavily impacted.

The erosion of manufacturing in favor of cheaper, foreign-sourced goods has undermined their ability to rise into, and stay in, the middle class, McKinsey authors wrote. The United States meets just 71% of its final demand with domestic goods, a smaller share than in Germany, Japan, or China. We import the rest. As a result of that, the United States has lost some 5.8 million manufacturing jobs between 1999 to 2009.

Starting in 2010, the U.S. saw a return to modest employment growth with the addition of 1.3 million jobs after the 2008-09 financial crisis. The pandemic led to another setback, erasing roughly 500,000 jobs, McKinsey estimated.

CPA is working on a new Job Quality Index (JQI) based on race and gender. A preliminary look shows that Blacks and Latinos are represented heavily in low-quality, low-wage jobs.

Latinos are heavily present in the hospitality and leisure sectors (24.1%), with Blacks being over-represented as a percentage of their population in public transportation (18.7%), government office jobs (17.5%), and education and healthcare services (14.8%).

One of the reasons why Black and Hispanic workers are at the bottom of our new JQI chart is due to their heavier weighting in low-paying service sector jobs. If we had more blue-collar manufacturing jobs, we are convinced that this chart would improve. One just has to look at the history of Detroit during the heyday of the automotive industry to see the economic and cultural benefits manufacturing booms can bring.

The tens of thousands of jobs lost in the auto sector over the last 10 years, and the plight of classic automotive hubs in Michigan, should serve as a good case study as to what the exodus of skilled manufacturing labor means to racial equity in the nation’s job market.

Save the Planet? Not with ‘Global Pollution Chains’

We like to call the focus on transoceanic shipping for everything from steel rebar to solar panels as being part of the global pollution chain. In many cases, we are outsourcing pollution.

By preparing to go green in the U.S. to prevent climate change, policymakers are inadvertently pushing companies to offshore their pollution to less environmentally rigorous countries. This hurts domestic companies that cannot compete with their rivals’ weaker regulations.

From McKinsey:

On April 21, Biden announced plans to cut CO2 emissions. This is good news for solar and wind. But where will our windmills and solar panels come from?

China wind turbine giant Goldwind has seen its installations in the U.S. go from just 2 in 2019 to 48 in 2020, according to the Global Wind Energy Council. Europe is our lead supplier, with GE Renewables making wind turbine blades in North Dakota. Their Rhode Island offshore wind project’s main parts – the turbine and blades — were mostly imported from France, where GE Renewables is headquartered.

China dominates this solar supply chain and CPA estimates that it accounts for more than 80% of the solar panels imported in the U.S. Some of the polysilicon that goes into making solar cells comes from Xinjiang, a region now infamously known as the home of large-scale detention centers for Uyghur Muslims.

Beyond solar and wind, if the U.S. is going to cut back on its CO2 emissions by outsourcing pollution to other countries, it’s like recycling plastics here only to watch them pile up in a landfill in India. It would be better if we recycled them here, for example, and created an industry to do it. It would be better if government wind-powered utility contracts required blades and turbines to be made here. The same with solar-powered utilities. If someone wants to put imported solar panels on their roof, that is their prerogative. But state and local governments need to support supply chains here. If not, America’s climate change policy will be yet another Asian jobs program.

“We need job and renewable production targets to go with these reduction plans,” says Michael Stumo, CEO of CPA. “Emissions targets are not enough as lowering these could either be job creators or job and industry, killers.”

CPA sent a letter to USTR Katherine Tai on April 22 to let her know that lowering emissions needs to be wedded to job creation, and not just in the American sales departments of companies installing Chinese solar panels.

CPA supports President Biden’s Executive Order expanding “Buy American” policies and the goals of the new “American Jobs Plan,” including the proposal to convert the federal vehicle fleet to American-made electric vehicles.

However, China dominates electric vehicle (EV) production now due to its massive domestic market, and U.S. automakers are moving electric vehicle production to other countries, such as Ford’s new Mustang Mach-E, made in Mexico. CPA’s automotive supply chain members are seeing their orders from automakers dwindle rather than shift to EV production. We have three new pure-play EV domestic car companies outside of Tesla.

Environmental advocates often promise that their policies will create millions of green jobs for U.S. workers. Unfortunately, when it is time to implement programs to achieve those goals, the environmental objectives often predominate while the jobs objectives are aspirational, CPA told Tai in its letter last week.

U.S. Semiconductors: A Collapsing Model

Like McKinsey said, the nation is facing what may be a “now-or-never moment” to inject new life into its industrial base. Semiconductors are a prime example of that.

We design them, but Samsung and Taiwan Semiconductor (TSMC) mostly make them. Our industry has taken on what is known as a “fabless” model, where the design, equipment, and IP are what matters. Manufacturing the actual chips to scale is mostly an afterthought.

That’s changing. But McKinsey warns that the remedy cannot come from grants, funding for R&D, retraining, and tax cuts alone. There needs to be a clearly articulated goal and a road map for achieving those goals so the U.S. is making, not just designing, microchips.

From McKinsey:

CPA published a white paper on semiconductors in March.

For starters, we argue that the U.S. must respond to this collapsing fabless model by strengthening the enforcement of the 2018 Export Control and Reform Act. Semiconductor equipment makers and electronic design automation tool companies must be prevented from selling to entities with Chinese military ties. Today, that enforcement is too weak.

We think the U.S. government needs to implement reforms to support a substantial increase in chip manufacturing with a goal of producing 50% of semiconductors in every major category from logistics to analog. This will strengthen U.S. national security and diversify supply and resiliency. Just as important, we think it will create hundreds of thousands of high-paying manufacturing jobs in the U.S.

The 16 ‘National Champions’: A Necessary Remapping

Supply-chain disruptions have become more frequent and more severe in recent years. The risks are only growing more pronounced in light of climate change, cyberattacks, pandemics, geopolitical uncertainty, and trade disputes. Resilience enables an economy to withstand various types of supply-chain shocks with minimal impact on public welfare and the operations of related industries that depend on key inputs, the McKinsey report states.

For McKinsey, if the U.S. had a “national champions” sectoral model, like China, the following 16 sectors would be the most vital due to their relevance to national security and their importance to overall supply chain resiliency.

From 1995 to 2019, the U.S. share of global manufacturing GDP dropped by an average of 6 percentage points across these 16 industries. As a result, the gross trade deficit grew by 7.5 percentage points, according to McKinsey.

From 1997 to 2016, foreign sourcing of the intermediate parts used in domestic car manufacturing rose from 10% to 15%. These trends, which were mirrored in other industries (and other advanced economies), either squeezed smaller suppliers out altogether or forced them into relentless price competition, McKinsey noted. In 2017, they analyzed firm-level financial results going back to 1990 and found that manufacturers with more than $1 billion in assets saw revenues grow by more than 2% annually. These are the globalist corporations, sourcing their wares from Asia (and selling there, as well).

At the same time, small and medium-size manufacturers posted negative growth.

These data points should drive home a clear message: the ability to make things domestically matters.

Industry leaders, policymakers, and the public alike have gained a fresh resolve to make the United States better prepared and more self-sufficient as the pandemic showed our weaknesses.

Port-side congestion today, with empty containers going to China in order to ship Made in China goods asap to the U.S., means that a lot of our post-pandemic recovery and stimulus checks are going to Asian sourced goods.

In February, the Biden administration ordered an immediate review of vulnerabilities in the nation’s supply chains. But Trump had done something similar. There are numerous bills in Congress that will address these issues. We need action on them, not endless reviews and investigations. We know what we are up against, from an overvalued dollar to China’s economies of scale backed by failsafe state subsidies.

Some in government are averse to China-like subsidies and picking favorite industries. If that’s not the chosen track to take, then something will need to be done with the dollar (like our MAC charge), or tariff protections on those 16 sectors highlighted by McKinsey.

If the United States manufacturer, and the workers that support it, are going to be forced to run a three-legged race in a potato sack, then they will increasingly need government to send someone onto the tracks for help. Preferably with tripwire against those running freer, with a mighty wind at their backs.

MADE IN AMERICA.

CPA is the leading national, bipartisan organization exclusively representing domestic producers and workers across many industries and sectors of the U.S. economy.

TRENDING

CPA: Liberty Steel Closures Highlight Urgent Need to Address Mexico’s Violations and Steel Import Surge

CPA Applauds Chairman Jason Smith’s Reappointment to Lead House Ways and Means Committee

Senator Blackburn and Ossoff’s De Minimis Bill is Seriously Flawed

JQI Dips Due to Declining Wages in Several Sectors as November Jobs Total Bounces Back from Low October Level

What Are Trump’s Plans For Solar in the Inflation Reduction Act?

The latest CPA news and updates, delivered every Friday.

WATCH: WE ARE CPA

Get the latest in CPA news, industry analysis, opinion, and updates from Team CPA.

CHECK OUT THE NEWSROOM ➔