Summary points:

- The import price of steel fell in the period following the 2018 imposition of a 25% steel tariff, an indicator that steel tariffs were not passed entirely onto consumers.

- Steel tariffs did not lead to a proportional rise in consumer prices of steel-intensive goods, such as automobiles. In many instances, firms will internalize small price increases before they raise prices.

- The assertion that tariffs are passed wholly onto consumers is theoretically unlikely, especially for products with complex supply chains such as steel.

- Tariff incidence – the measure of who pays a particular tax or charge – depends on the elasticity of demand and supply in both the domestic and foreign markets. Economic studies of tariff incidence have long demonstrated that the cost is shared, in varying degrees, between buyers and sellers at each level.

- In the context of imported goods, tariffs are more likely to be borne by foreign sellers where the domestic production constitutes a greater share of the market.

- Tariffs are also more likely to be paid by foreign sellers when the US has considerable buy-side market power.

Introduction

Many policy makers and reporters have assumed that tariffs are passed entirely onto consumers. We believe this was unlikely to happen in theory and based on the evidence did not happen in the case of the steel tariffs. Tariff incidence, like tax incidence, is a question of mathematics and market dynamics not ideology. Basic economic theory suggests that only under extreme circumstances would final consumers pay a full upstream cost increase of a complex supply chain, whether tariff induced or otherwise. In extreme cases, every market interface at every level of the supply chain would have to perfectly and entirely passes on the price increase, we do not know of any instance in which this has occurred.

We further analyzed the roughly one-year period when the Trump tariff on steel was applied most broadly. In March 2018, the Trump administration announced a 25% tariff on steel under Section 232 of the 1962 Trade Expansion Act. Steel tariffs on Canada and Mexico, who are among the foreign largest suppliers of U.S. steel, were removed about a year later in May 2019. The time frame is also limited because steel and auto prices changed dramatically after COVID-19 began.

A look at the data shows that following the 2018 steel tariffs, the import price of steel fell. When U.S. steel import prices fall, it means that steel is now relatively cheaper to buy than sell (export) on the global market, which economists call an improvement in the terms of trade. This means that U.S. national income rises.

Consumer prices of steel-intensive downstream goods such as automobiles, did not increase proportionally to the tariff. The lack of a tariff pass-through on automobile prices reflects the dynamics of price determination, which involves not only the market structure but also consideration for how firms respond to input price increases. Together, this means that steel tariffs did not or would not proportionally raise consumer prices.

This analysis is part of a continuing effort at CPA to evaluate how tariffs affected the U.S. economy. Tariffs are a legitimate economic development tool that can improve economic outcomes and, we believe, should not be rejected outright.

Market elasticities are important to determine whether buyers or sellers absorb a tariff

Economic theory shows that tariff incidence between buyers or sellers is different for every product, and at every level of the supply chain. More precisely, it depends on the relative elasticity of demand and supply within domestic and foreign markets for a specific product.

The elasticity of demand or supply for each product depends upon how responsive quantity (volume of sales) changes when price changes. Tariffs, like a tax, make the selling price higher. A buyer will pay the full amount of this tariff price increase if they demand the tariff good perfectly inelastically, or unresponsive to price changes. Alternatively, the seller will pay the full amount of the price increase if the demand for the tariffed good is perfectly elastic, or responsive to price increases. Essentially, whoever is more inelastic will pay more, and only when we have perfect elasticity or inelasticity does someone pay the full amount.

Consider two examples on tariff incidence: first where a buyer pays a greater share and second where a seller absorbs more as a cost.

Tariff Incidence Example 1: Prescription Drugs

For the first example, consider a tariff on a good for which there is relatively inelastic demand. “Necessity goods” such as prescription drugs are classic examples. That is because consumers will buy the same amount whether the price goes up or down. For the market to be truly inelastic, there must also be few sellers with considerable market power. Under these circumstances, consumers have no choice but to accept price increases because (1) they need it and (2) they have no alternative.

Prescription drugs sellers have considerable market power in relation to end use consumers. This means that supply will be somewhat inelastic because there will be fewer suppliers to meet demand if price changes. There will be some domestic producers of prescription drugs, but assume that foreign suppliers can produce them at lower prices, and as such, meet a significant portion of domestic demand. In this example, both supply and demand are inelastic, but if consumer demand for prescription drugs are relatively inelastic, they will pay more of the burden of a tariff.

This simple example reveals that a cost increase, such as a tariff on imports of prescription drugs, is more likely to be passed on to domestic consumers. However, it should be noted that consumers do not buy medicines at the Port of Los Angeles. There are several links in the supply chain from importers to wholesalers to distributors to pharmacies that a tariff would have to passthrough to be fully passed on to consumers. Further, firms will often choose not to raise prices first in order to remain price competitive, instead firms will turn to cost-saving methods to absorb price increases.

Tariff Incidence Example 2: Steel

Next consider a tariff on goods that have a more elastic demand than prescription drugs, such as steel. Even though steel is a very critical resource, demand for foreign steel is more elastic because alternative sources exist, namely domestic production.

A second key consideration is that the U.S. is the largest steel customer for several steel producing countries. Our domestic consumption volume provides significant buy-side bargaining power in relation to those foreign sellers.

In this example, tariff incidence would fall more on foreign sellers who would have to lower the price they accept by paying a tariff. A reduction in the import price of steel, holding export prices constant, means that it is now relatively cheaper for U.S. to buy than sell steel. In other words, an increase in the ratio of export to import prices is an improvement in our terms of trade.

Long supply chains mean consumers unlikely to pay most of the tariffs

Despite the empirical studies that have claimed that consumers paid the full amount of the section 301 (China) tariffs or section 232 (steel and aluminum) tariffs, it is very difficult to imagine a situation in which that would be possible. Unlike sales taxes, tariffs are not necessarily levied directly in the market they are sold to consumers. Tariffed goods are almost always purchased by different companies several times over before they reach a market where consumers can buy them. In order for the downstream final consumer to pay the full tariff, the individual market dynamics at every level of the supply chain must have a perfect scenario of supply elasticity or demand inelasticity.

Steel is a raw material that can be imported through our port system. If a tariff of 25% is placed on steel, then the importers that buy foreign steel will pay the entire 25% increase only if the supply of foreign steel is perfectly elastic or the demand for steel is perfectly inelastic. We know this is not likely in reality because we have alternative sources of raw steel materials, namely our own supply. But lets assume a fictional case in which the tariff is fully passed through anyway.

Tier 3 suppliers buy the imported steel to make semi-finished products. These firms sell to a broad array of manufacturing customers including automotive, aerospace, defense and other markets. Tier 2 firms then purchase the Tier 3 products to fabricate metal parts and components for automobiles.

After this, Tier 2 firms sell their fabricated products to Tier 1 firms like Bosch or Denso Corp. These Tier 1 firms then produce automotive grade systems that are sold directly to automobile manufacturers, also known as “original equipment manufacturer” or OEM’s.

You would think that the last step in the supply chain ends with the manufacturers, but in fact we have to consider another market, where automobile manufacturers sell to their dealerships. That is, a dealership sells directly to consumers, not automobile manufacturers. Dealerships order automobiles based on the market they sell to consumers in.

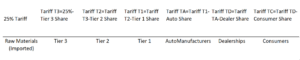

Figure 1: Steel Tariff Pass-through in Automotive Market

The question is, how can the original 25% tariff can be passed through Tier 3, Tier 2, Tier 1, OEM’s, and finally through dealerships in every market? Each level of figure 1 represents its own supply and demand dynamics. Tier 3 companies supply goods that Tier 2 companies demand. The 25% tariff paid by Tier 3 companies can only be passed entirely onto Tier 2 firms if the supply of Tier 3 steel is perfectly elastic or the demand for steel by Tier 2 firms is perfectly inelastic. The same is true for Tier 2 firms selling to Tier 1 firms and so forth. Therefore, at every level, for the tariff to be fully passed through to final consumers, each Tier must have a perfectly inelastic or elastic component. Either case is hard if not impossible to imagine. It is more realistic that each level has different market dynamics and therefore at each Tier the 25% tariff gets shared along the way.

Figure 1 shows that at every level of the supply chain, the tariff that gets carried through depends on the tariff incidence in the previous level. So for instance, if the original tariff is 25% but Tier 3 firms pay 10% of the tariff, then the prevailing rate that is facing the next level is 15% (this is not exactly correct but for simplicity the idea that a smaller tariff gets passed through to the next level is). This means that every level absorbs some of the tariff so that the final tariff incidence faced by consumers cannot be equal to the full amount of the original tariff. The only way this is possible is if at every level the entire tariff gets passed through—in the case of a perfectly elastic supply or inelastic demand, neither of which is characterizes the automotive supply chain.

The Evidence Suggests Consumers Did Not Pay the Full Steel Tariff

The Section 232 steel tariffs took effect in March 2018. They have been repeatedly criticized for raising the price of steel.[1] However, after a brief runup in the price as steel service centers and steel users scrambled for product, the steel tariffs were introduced, and the price (for hot rolled steel?) actually fell.

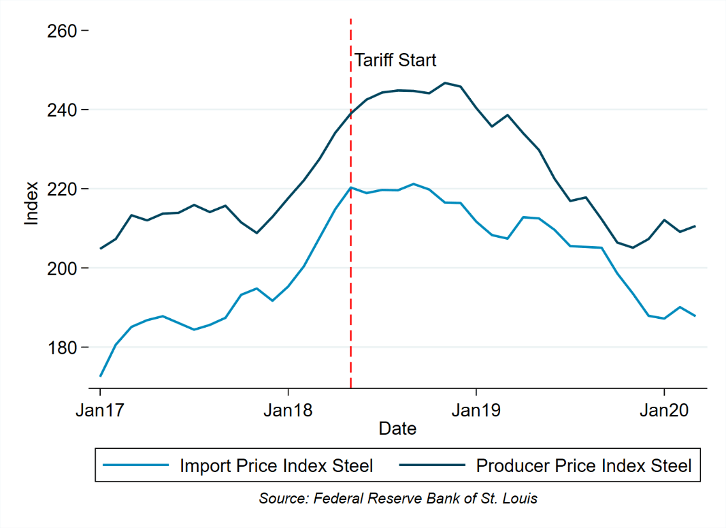

Figure 2 shows that both producer prices and the import price of steel fell following the 2018 tariffs. Between December 2017 and December 2019, the price of imported steel fell by 2% and the domestic producer price fell by 2.6%. A fall in the import price following the tariff is a terms of trade gain, suggesting that the tariff is shared between importers and exporters of steel.

Figure 2: Steel Import Price, Producer Price, 2017-2020

Why would exporters pay part of the steel tariffs? A part of the answer is that the U.S. is a major buyer of steel in relation to the global market. This buy-side market power provides the ability to push back against attempts by foreign steel sellers to fully pass the tariffs on in the form of price increases. America is the world’s largest importer of steel. The largest suppliers to the U.S. are very dependent on our purchases because we are their dominant customer.

For instance, the U.S. gets 18% of its steel imports from Canada, while those imports represent 83% of all Canadian steel exports. In simple language, Canada needs U.S. steel customers more than those customers need Canada. This means that a tariff on steel would likely be shared as the US has considerable market power as Canada’s largest buyer of steel.

Another part of the answer is that the U.S. is a major producer of steel, allowing buyers a choice to substitute domestic or foreign supply. If domestic suppliers did not exist in significant quantities, foreign sellers would have more power to pass the tariffs on to buyers.

While the U.S. consumes about 100 million tons of steel a year, it produces most of that amount, about 75%, domestically. In a market where the U.S. produces most of what it consumes, tariffs on any imports of steel should not lead to a dramatic increase in domestic prices because domestic producers can raise their production to fill the gap. [2]

Automobile Price Effects from the Steel Tariffs

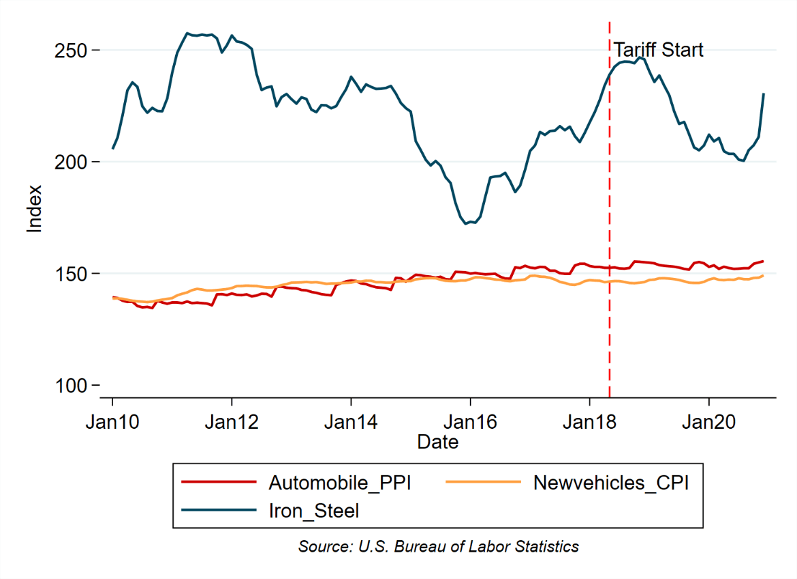

How did steel price changes affect domestic production of steel intensive goods, such as automobiles? The short answer is that the steel price change did not lead to any visible price increase to end consumers of cars and trucks. Figure 3 shows that regardless of steel price changes, caused by tariffs or other factors, the price of new automobiles remained relatively unchanged. That is, steel tariffs did not lead to an obvious increase in the price that consumers pay for automobiles. Even past changes in the steel price, irrespective of tariffs, did not cause proportional changes in the price of automobiles.

Figure 3: Producer & Consumer Price Index for Automobiles & Intermediate Input Costs

The relatively unchanged price of automobiles reflects at least three things. First, automotive manufacturers do not buy steel. Rather they buy parts and components made from steel. There are several supply chain levels between the steel companies and the auto manufacturers including those manufacturing parts and components. The market interfaces at each level must be perfectly respond to price for tariffs to be fully passed on. They are not.

Imperfect competition in the market for automobiles limits price changes. The automobile market is relatively concentrated market with few suppliers. Further, these suppliers are limited globally not just in the US market. This means that despite a large U.S. consumer market, input price changes in the U.S. market are not likely to have a major effect on auto prices, which is consistent with the data shown in figure 2 above.

Further, companies will often internalize cost increases before they raise prices. A company can take cost-saving measures or accept slightly lower profits. Further, the automobile market is concentrated globally, losses in one market does not change their overall cost considerably and therefore neither would their market price. Steel is a small part of the total cost of a vehicle (on the order of 3%-5%) and auto producers set vehicle prices based on competitive dynamics as much or more than cost.

Earlier U.S. tariff experience shows tariff cost shared by producer and consumer

Economic studies of the evidence of past tariffs suggest a wide range of tariff pass-through rates onto consumers. For instance, consider the tariffs on imported sugar in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. During this time, the U.S. was a major consumer of global sugar production. A study by Douglas Irwin showed that sugar tariff increases were paid 60% by producers and only 40% by U.S. consumers. Most interesting about this paper was the asymmetry found in the effect of raising or lowering tariffs: tariffs are absorbed by buyers more when they increase but passed more onto the consumer when they decrease. The reason is the asymmetric response in quantity demanded to tariff induced price changes: domestic buyers anticipate changes in tariffs and will buy more today when they anticipate an increase in tariffs and will buy less if they believe tariffs will decline.[3]

Another example is tariffs on Japanese trucks.[4] Prior to 1980, Japanese trucks were generally imported in parts, as cab or chassis, a classification with a tariff rate of 4%. This rate of 4% was significantly smaller than the 25% chicken tax imposed on all imported trucks since 1964. Political attention and an ITC investigation led to a reclassification of cab or chassis to complete trucks, and consequently a higher tariff rate of 25%. A study by Robert Feenstra in 1988 showed that this new higher tariff on Japanese truck imports only raised their consumer price in the U.S. by 13%, for a pass-through rate of 60%.

The higher tariff on Japanese trucks was only partially passed onto the consumer because of the increased competition that followed the new trade protection. Before the 25% tariff, Japan dominated the market for lightweight trucks. After the 25% tariff, market competition in lightweight trucks increased. Instead of buying from Japanese producers, U.S. auto producers introduced their own lightweight trucks. Further, Japanese firms like Mitsubishi began selling trucks independently. A more competitive market means that Japanese truck makers are in less of a position to raise prices and therefore less able to pass the tariff onto consumers.

Conclusion

Tariff incidence depends on the economics of, and elasticities in, a particular market. There are several empirical studies that show how tariffs are not wholly shared by consumers for different products. These studies show that tariffs should be assigned in markets where we have relatively more market power. Just like other taxes, tariffs are not a universal tax wholly paid by consumers; tariff incidence depends on the relative elasticity of supply and demand in both the foreign and domestic markets. Further, only under extreme and highly unlikely circumstances will tariff incidence be passed through entirely along all channels of a supply chain. The evidence discussed here shows why the 25% tariffs on imports of foreign steel were not or could never be wholly passed through to the final consumer.

[1] Trump’s steel tariffs cost U.S. consumers $900,000 for every job created, experts say, The Washington Post, May 7 2019

[2] US International Trade Administration, 2017, CPA Calculations

[3] Douglas Irwin, Tariff Incidence: Evidence from U.S. Sugar Duties, 1890-1930, N. 20635

[4] Robert C. Feenstra, Symmetric pass-through of tariffs and exchange rates under imperfect competition: An empirical test, Journal of International Economics, Vol 287, Issue 1-2, pg 25-45, August 1989