Editor’s note: An excellent article outlining only a few of China’s horrible, terrible practices regarding tech theft and commercial espionage.

DuPont Co. suspected its onetime partner in China was getting hold of its prized chemical technology, and spent more than a year fighting in arbitration trying to make it stop.

[Lingling Wei and Bob Davis | September 25, 2018 | WSJ]

Then, 20 investigators from China’s antitrust authority showed up.

For four days this past December, they fanned out through DuPont’s Shanghai offices, demanding passwords to the company’s world-wide research network, say people briefed on the raid. Investigators printed documents, seized computers and intimidated employees, accompanying some to the bathroom.

Beijing leans on an array of levers to pry technology from American companies—sometimes coercively so, say businesses and the U.S. government.

Interviews with dozens of corporate and government officials on both sides of the Pacific, and a review of regulatory and other documents, reveal how systemic and methodical Beijing’s extraction of technology has become—and how unfair Chinese officials consider the complaints.

China’s tactics, these interviews and documents show, include pressuring U.S. partners in joint ventures to relinquish technology, using local courts to invalidate American firms’ patents and licensing arrangements, dispatching antitrust and other investigators, and filling regulatory panels with experts who may pass trade secrets to Chinese competitors.

In DuPont’s case, the dispute concerned a process to produce supple textile fibers from corn, a $400 million business for the company in 2017. The antitrust investigators, say the people briefed on the raid, told DuPont to drop the case against its former Chinese partner.

U.S. companies have long complained that Beijing pressures them to hand over intellectual property. More recently, their concerns have escalated as China turns into an advanced rival in industries ranging from chemicals to computer chips to electric vehicles.

Coerced technology transfer is now a central part of the spiraling U.S.-China trade fight, a standoff that appears to be only more entrenched. The White House estimates China inflicts $50 billion yearly in damages on U.S. companies. That transfer, U.S. executives regularly complain, weakens American businesses’ competitiveness and undermines the incentive to innovate.

Chinese authorities referred questions to a paper issued on Monday by the State Council, China’s cabinet, that says: “American companies in China have received huge returns through technology transfer and licensing, and are the biggest beneficiaries of technical cooperation” and that U.S. companies enter partnerships voluntarily.

“China’s offer to the world has been straightforward,” says a policy maker in Beijing. “Foreign companies are allowed to access China’s markets but they would need to contribute something in return: their technology.”

U.S. companies have gone into China with eyes wide open, for the most part, and many are wary of going public with complaints. American companies initially brought the idea of joint ventures to China as a way to get access to a market of 1.4 billion people and tap a low-cost workforce. The bargain included helping Chinese firms become more technologically advanced.

At a January U.S. Chamber of Commerce dinner in Washington, executives pressed U.S. Ambassador to China Terry Branstad not to hit Beijing too hard on technology issues,according to dinner attendees. China has many ways to get even, warned Christopher Padilla, a vice president of International Business Machines Corp. , which licenses technology to Chinese firms.

“If someone gets knifed in a dark alley, you don’t know who did it until the next morning,” Mr. Padilla said at the dinner. “But there has been a murder.”

DuPont briefed U.S. officials on its problems but didn’t want its case raised in trade talks, say some of the people familiar with the case. Its former Chinese partner, Zhangjiagang Glory Chemical Industry Co., continues to sell chemicals used to make fibers that DuPont believes are knockoffs of its technology. DuPont and Glory declined to make executives available for comment.

China’s antitrust regulator said “the investigation is still ongoing,” declining to elaborate.

‘Notable pressure’

About one in five members of the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai say they have been pressured to transfer technology, according to a survey conducted in the spring. Of those companies, 44% in aerospace and 41% in chemicals report “notable pressure.” China considers both industries strategically important.

Trading market access for technology dates to Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping’s effort to launch the pro-market policies that propelled China’s rise. General Motors Co. executives on an exploratory 1978 visit proposed a joint venture with a local company to boost a then-antiquated Chinese industry, say Chinese government advisers, historians and auto-industry executives.

The idea fit with Deng’s desire to obtain Western technology but limit Western influence. China “needs to give up portions of the domestic market in exchange for advanced technologies we need,” he pronounced in 1984. The policy was a success, according to a March 2018 paper by economists at the universities of Colorado, Hong Kong and Nottingham, who found that foreign technology “diffuses beyond the confines of the joint venture” and boosts competitors’ technology.

Foreigners bring cash, technology, management know-how and other intellectual property while the Chinese partner usually contributes some land-use rights, financing, political connections and market know-how. As the practice increased, one U.S. administration after another, with only modest success, pressed Beijing to ease requirements that U.S. companies fork over technology. The Trump administration says it wants to “change the paradigm” by hitting Beijing with tariffs.

China mandates that foreign companies wanting to open or expand in 35 sectors do it through joint ventures, though it announced a plan in April to phase out rules requiring foreign auto makers to share factory ownership and profits with Chinese companies by 2022.

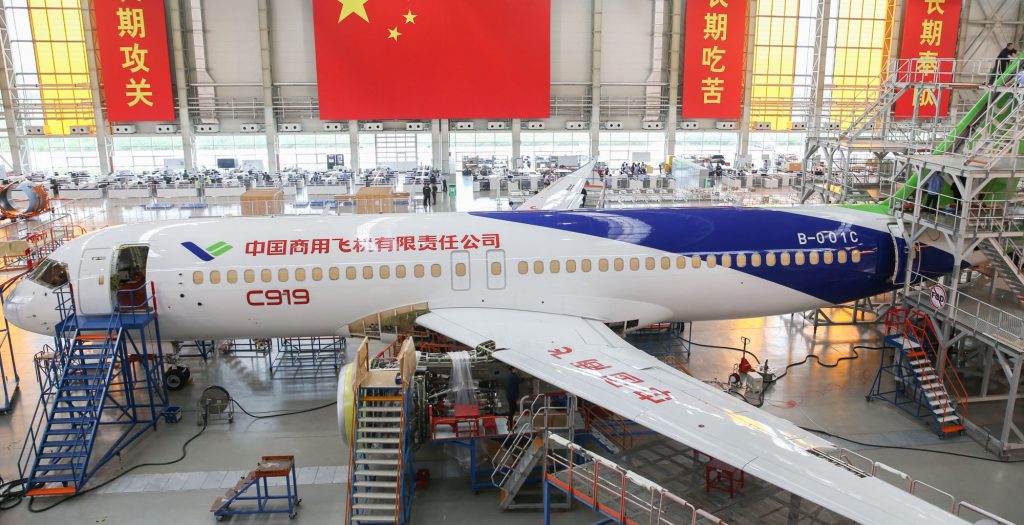

The arrangement has worked for some. When China set out to build its first large commercial passenger jet in 2008, state-owned Commercial Aircraft Corp. of China made clear it would buy components only from joint ventures whose foreign partners would share technology. General Electric Co. agreed.

GE’s venture with state-owned Aviation Industry Corp. of China now is a main supplier of avionics for the domestic C919 aircraft. The joint venture helped GE avoid writing down a struggling avionics unit, according to former and current GE employees.

GE says “there was never a write down at our avionics business, nor was there risk of one.” It says, referring to intellectual property, that GE is “highly sensitive to the protection of our IP whether in our wholly-owned operations or in our” joint ventures.

Advanced Micro Devices Inc., a Silicon Valley chip company, entered a joint venture in 2016 with Chinese private and state-owned entities, including the government’s Chinese Academy of Sciences. AMD licenses microprocessor technology to the venture and is developing new computer chips with it.

AMD has received about $140 million in licensing through 2017, enough to help boost it into the black last year for the first time since 2011. “We created a joint venture that was very much a win-win,” AMD Chief Executive Lisa Su said at a 2016 conference. An AMD spokesman says the joint venture is “part of our strategy to create a complementary product offering.”

Chinese leaders see innovative technologies as forces to propel its industries up the value chain into more sophisticated sectors and the country into rich-nation ranks. To ensure foreigners bring their best, phalanxes of regulatory panels scrutinize foreign investments to make sure they meet government goals.

Huntsman Corp. has singled out these review panels as a conduit for siphoning trade secrets. The Woodlands, Texas, chemicals maker is thriving in China, which accounted for about 14% of its 2017 revenues.

Regulatory panels, packed with industry experts, must approve many chemicals before they can be produced in China and require detailed information on formulas and production processes, say U.S. trade groups and chemical firms. “Enough information to duplicate the product,” is how the American Chemical Council trade group put it in a filing to the U.S. government.

For Huntsman, these panels have drilled down on specialized knowledge, such as how it makes plastics with high transparency and elasticity—the kind of material often used for making sports shoes—people close to Huntsman say. Soon after those experts conducted their evaluations, local competitors used the same kind of technology in their own products, they say.

Huntsman is battling over a crown jewel of its business, a black dye used in textiles that is less polluting to make. It filed a lawsuit in Shanghai against a Chinese company for infringing a patent on the dye in 2007. Huntsman then found a court-appointed review panel stacked against it, it said in a 2011 complaint it filed with the U.S. Commerce Department.

The three-panel members included an engineer from the company Huntsman was suing, another from a local dye-research group and a third who once worked at a local dye firm, according to the complaint and people with knowledge of the matter. The experts’ work “effectively turned them into allies and ‘spokespersons’ ” for the Chinese competitor, the complaint said.

Litigation of the patent-infringement case has dragged on. Huntsman has asked the Trump administration to consider blocking Chinese firms if they set up operations in the U.S. using disputed Huntsman technology.

For foreign auto makers, the review panels have become a battleground over electric-vehicle technology. New vehicles must get government approval before mass production, undergoing a mandatory technology audit that usually lasts several days, foreign makers say.

An audit this year convinced an employee at one foreign auto maker there was “clear evidence of collusion” between the audit team and Chinese auto makers. When the audit began, the person says, inspectors asked for only the blueprints of the electric-vehicle components the foreign company was striving to protect from its Chinese joint-venture partner.

“Somehow they knew exactly the areas to look at,” the person says. “There wasn’t a single question about any of the other very complex systems on the vehicle.”

The DuPont raid

DuPont also shared information with its Chinese partner, Zhangjiagang Glory, when it licensed the Chinese firm in 2006 to produce and distribute Sorona, the textile polymers made from corn. Within DuPont, the Glory deal was called a “tolling” partnership—a relationship that serves as a kind of toll to enter the market. DuPont trained Glory to set up a factory to produce Sorona polymers and to spin them into fibers.

Around 2013, say the people familiar with the case, DuPont didn’t renew Glory’s license amid suspicions the Chinese firm was ripping off its intellectual property to sell products similar to Sorona, which has grown to a $70 million business in China. DuPont filed two arbitration cases in China, alleging patent infringement, with hearings stretching through 2017.

Around that time, officials with the National Development and Reform Commission’s antitrust division in Beijing took an interest in the matter and started holding meetings with DuPont. The commission showed little interest in DuPont’s planned merger with Dow Chemical Co., completed late last year, even though it launched an antitrust investigation into the combined entity in December.

Rather, investigators focused on the DuPont-Glory standoff, say the people briefed on the case. During three days of meetings in December, DuPont became worried about a raid on its office. It planned an employee-training session on how to deal with one, but the investigators showed up first.

An investigator told DuPont officials they were looking at antitrust behavior, specifically their unwillingness to license technology to Chinese firms and their pursuit of the Glory case, say these people. DuPont officials, they say, now fear that even dropping the case won’t be sufficient to satisfy Beijing, which may want a hostage in the trade fight with Washington.

Trump-administration officials see cases like this as evidence of China’s economic aggression. “The combination of naiveté and hubris on the part of U.S. companies seeking to enter the Chinese market, coupled with a sophisticated Chinese effort to extract technology has been a lethal combination,” says White House trade adviser Peter Navarro, a China hawk.

During August trade talks, U.S. negotiators pressed Beijing about coerced technology transfer. They cited memory-chip maker Micron Technology Inc., which filed a lawsuit in U.S. District Court in California in December alleging technology theft by Fujian Jinhua Integrated Circuit Co. Jinhua sued Micron in January in a court in Fujian province—whose government partly controls Jinhua—and won a temporary order blocking some Micron subsidiaries from selling products in China that each company claims patents to.

Jinhua declined to comment. In a July statement, it said Micron has “recklessly” infringed on its patents. Micron says it intends “to vigorously protect our intellectual property and business interests through all available means.”

Chinese negotiator Commerce Vice Minister Wang Shouwen dismissed the concerns in August trade talks, say officials familiar with the talks. Micron and Jinhua “are like brothers,” Mr. Wang said, according to the officials, “and brothers fight.”