Talk to anyone in the Biden administration and they’ll tell you that their economic policies will be governed by two things – climate change and inclusive economics. How we achieve those goals might depend on how well America’s economic progress on this front works for minorities, namely Black- and Hispanic-Americans.

On the climate side, it means a focus on solar and wind, electric cars, and battery materials. President Biden says climate change means jobs, but many environmental activist groups and K Street lobbyists for importers believe that the climate crisis is too grave to wait for American manufacturing to ramp up. You have to import solar panels and wind turbines asap, they say. This is not inclusive, unless you’re an Asian, in Asia. Importing more solar and wind products means less opportunity to manufacture them here. And that means less opportunity for blue-collar workers, as well.

For inclusive economics, it can only mean one thing: promoting and supporting an economy that provides opportunities for more minorities. That is because, outside of Asian-Americans, the U.S. economy has a long way to go if it wants to look the way the White House wants.

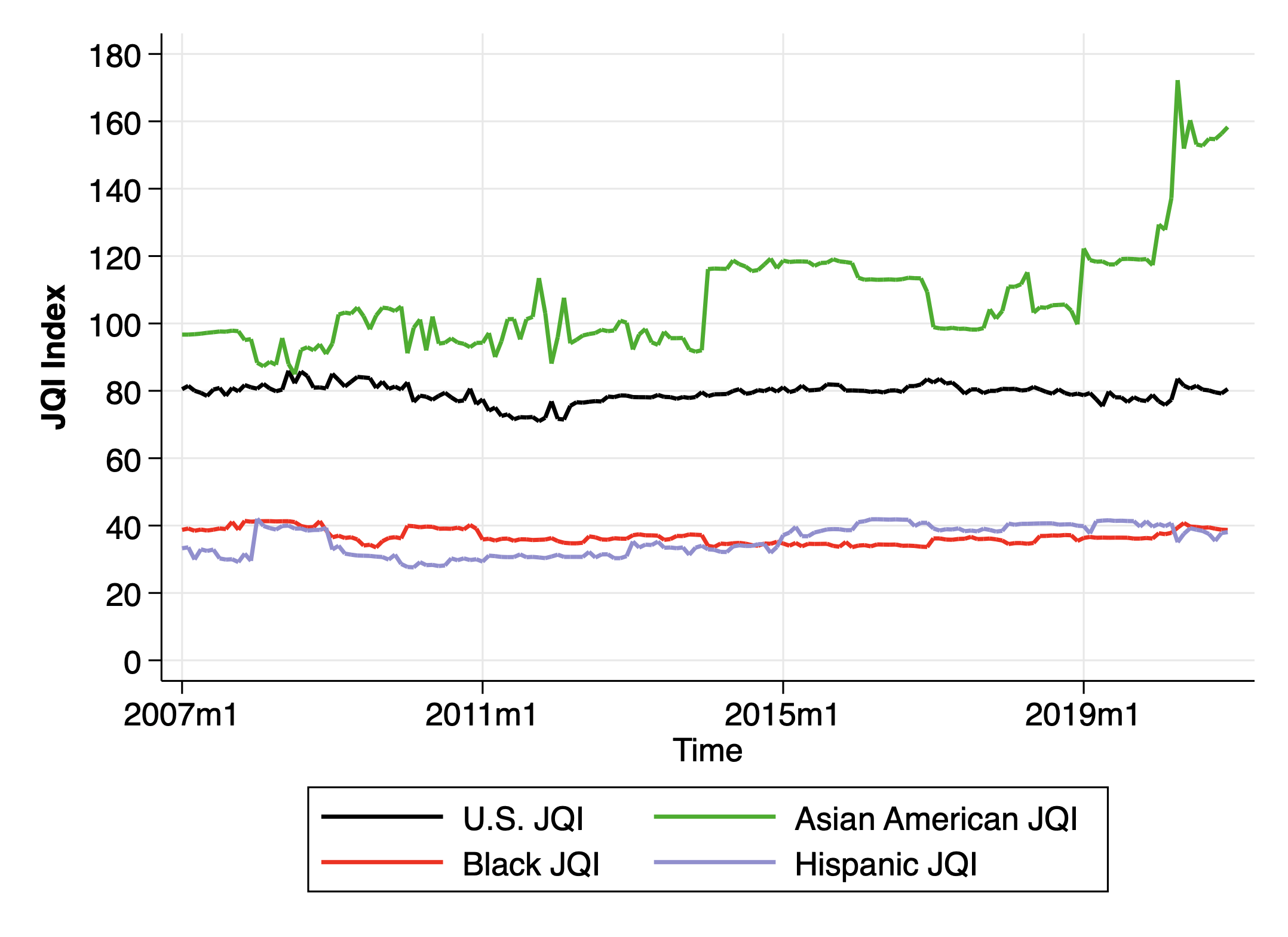

U.S. JQI vs. Minority JQIs, 2007–2020. Black and Hispanic America Trailing Behind

CPA economists Jeff Ferry and Amanda Mayoral took our Job Quality Index and put a different lens on it this time. Instead of gauging if the U.S. economy was adding more high-quality than low-quality jobs (a computer manufacturer versus a Target cashier), we measured the JQI of three minority groups: Asian, Black, and Hispanic American JQI’s.

CPA economists Jeff Ferry and Amanda Mayoral took our Job Quality Index and put a different lens on it this time. Instead of gauging if the U.S. economy was adding more high-quality than low-quality jobs (a computer manufacturer versus a Target cashier), we measured the JQI of three minority groups: Asian, Black, and Hispanic American JQI’s.

CPA found what many would have suspected: Black American job quality is far worse than that of the total population. The Black Job Quality Index for 2020 was 38.7, whereas the average JQI for the total U.S. private-sector production and nonsupervisory workforce is in the 70s. For the Black nonsupervisory workforce, 72% of their jobs are low quality, paying less than the average worker in non-executive level paying positions.

More than any other group, Black Americans seem to be paying the price for the decline in U.S. job quality in recent decades, much of it due to a combination of automation, centralized online retail, and the offshoring of quality manufacturing jobs. They also end up getting more of the lower quality, often part-time jobs in restaurants and retail, as well.

Similar to the Black JQI, the JQI for Hispanic Americans was 38.1 in 2020, also less than half the U.S. JQI for all workers combined. In 2020, 28% of Hispanic American employees held high-quality jobs and 72% were in low-quality employment.

Although far below the U.S. average, the Hispanic American JQI actually rose 29% since 2007, when it was just 29.5. The increase in the Hispanic American JQI was driven largely by the growth of Hispanic jobs in higher-paying health care services and employment on construction sites.

We believe the best way for the job quality of both Black and Hispanics to rise on this index is to create more opportunities in high-quality manufacturing jobs.

See CPA’s Working Paper: Quantifying Job Quality for U.S., Black, Hispanic & Asian American Workers

The U.S. will reach a trillion-dollar trade deficit either in 2021 or 2022 due to our continued focus on Asian imports. The more manufactured goods we import, the less manufactured goods we make. The less we make, the higher the prevalence of low-quality employment, especially among Black and Latino workers.

Some Workforce Statistics

The JQI gathers data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) to come up with its indexes. Here’s a look at where Blacks and Hispanics constitute a greater percentage of the workforce than their percentage of the population.

According to the BLS, Black people make up 12.1% of the workforce. They are 14% of the population, though this includes children and retired people. In some manufacturing sectors, they are more prevalent on the factory floor than in society at large.

Black employees account for 17.7% of workers making household appliances. So if your Frigidaire refrigerator is made in Mexico now, that’s one less job in small towns like Evansville, Indiana, where around 13% of the population is Black and a Whirlpool factory closed there some 10 years ago.

In another example, after many years of shunning Black workers and city factories, as was the case in Detroit back in the 1960s, the auto industry has been a solid home for good-paying blue-collar workers who do not want to “learn to code”. Some 18.2% of auto manufacturing is comprised of Black staff, well above its portion of the working-age population.

Now think of the impact on the auto sector due to climate-related government policies. If the move to battery-powered vehicles means fewer parts (no more combustion engine), then it means fewer jobs. If you want to keep the auto sector a bellwether for middle-class Black families from Alabama to Michigan, then Washington will have to make it so EVs are made here.

The Ford Mach-E Mustang, an iconic American model, isn’t made here. It is made in Mexico. That’s good for Mexico; less good for Ohio and Michigan where Ford operates. Ford has 8 assembly lines in the U.S. It has seven in China, though most of that is for the Asian market. Ford has two factories in Mexico. Ford’s biggest manufacturing center is its Kentucky truck plant in Louisville. It has a staff of around 8,200. While we don’t know the percentage of Blacks and Hispanics in its workforce there, we do know that Louisville’s demographics are 23.6% Black. The Kentucky truck plant is an opportunity for everyone in Louisville that isn’t going to get rich as a YouTuber, or is an A+ STEM student on their way to Stanford.

Moreover, Lucid Motors, a new battery-powered automaker, recently built a new factory in Casa Grande, Arizona. Casa Grande is 43.7% Hispanic.

The auto sector is an important one for minority labor. Washington needs to think about how climate change policies are changing that entire supply chain and strongly consider policies that expand manufacturing job opportunities from batteries to motors to robotics to final assembly. (The U.S. has no domestic industrial robotics manufacturers for making cars. The robotic arms making our cars are all Asian and European brands.)

Here are where the overwhelming number of Black workers are employed in terms of their percentage of the workforce versus their working-age population:

| Employment Sector |

Percentage of Workforce

|

| General Merchandise stores, wholesale clubs |

20.3% |

| Transportation and warehousing |

20.7% |

| Storage facilities |

23.5% |

| Postal/delivery services |

24.8% |

| Taxi/limo service |

27.1% |

| Private security/policing |

28.4% |

| Home healthcare services |

28.8% |

| Bus drivers/metro operators |

33.7% |

Now for Hispanics.

According to the BLS, they account for 17% of the working-age population and make up 18% of the U.S. population today.

For the manufacturing sector, in particular, Hispanics constitute 24.4% of metallurgy work, 21.8% of glass manufacturing, 29.8% of concrete manufacturing, and 23.4% of aluminum manufacturing and processing. They also make up 24.1% of the furniture-making industry, an industry nearly wiped out by Chinese dumping a few years ago.

Hispanics are nearly a third of what is left of the American textile and apparel industry. We still do make clothes in the U.S. If not, the business would go to Central America and Asia and maybe some of those people would return to those countries. But many more who were born and raised here and have a life here would probably be forced into service sector jobs in their community.

Latinos are a massive part of America’s manufacturing base for both goods and non-durable goods. But the sectors of the U.S. economy where they dominate by nearly a factor of 2-to-1 are all low-end service work, much of it part-time:

| Employment Sector |

Percentage of Workforce |

| Dry cleaning |

26.3% |

| Residential maid services |

35.2% |

| Building cleaning services |

42.2% |

| Car washes |

42.2% |

| Landscaping |

42.5% |

The above table is for the non-executive workforce, so this does not include Latino owners of those companies, whom CPA assumes would be doing well economically.

Most minorities live in large urban centers where they dominate the services sector – whether it be public transportation or healthcare. Manufacturing largely exists outside of those urban centers, in smaller cities and towns nationwide.

CPA believes that building a more inclusive economy means creating blue-collar and so-called “new collar” jobs (derived from vocational training and apprenticeships, not four-year degrees) that lead to opportunities for Blacks and Hispanics outside of the crowded urban centers of the country.

The JQI Minority Index shows that one of the best ways to lift people up the economic ladder is to provide them with ample job opportunities outside of the urban service, and into the manufacturing sectors that do not always require a college education.

Recognizing that supply chains are complicated, Biden’s own plans to tackle the climate, for example, is one way to begin promoting the administration’s “inclusive economics” push and use the “green tech” space as a case example.

For Blacks and Hispanics, their lackluster representation in this segment of the U.S. economy has, in part, led to their much lower position on the Job Quality Index.

Manufacturing jobs not only pay better than the low-quality service sector jobs, they offer on the job training, better benefits, and a path for career advancement, which leads to improvements in socioeconomic status for individuals, families, and the communities where they live.

Increasing automation will hit all industries. Nevertheless, manufacturing companies have a vested interest in training and keeping their staff, where many service industries regard employees as disposable and interchangeable. If you want to build an inclusive economy, it starts with building things.

Here’s A Way To Make The American Economy More Inclusive

Talk to anyone in the Biden administration and they’ll tell you that their economic policies will be governed by two things – climate change and inclusive economics. How we achieve those goals might depend on how well America’s economic progress on this front works for minorities, namely Black- and Hispanic-Americans.

On the climate side, it means a focus on solar and wind, electric cars, and battery materials. President Biden says climate change means jobs, but many environmental activist groups and K Street lobbyists for importers believe that the climate crisis is too grave to wait for American manufacturing to ramp up. You have to import solar panels and wind turbines asap, they say. This is not inclusive, unless you’re an Asian, in Asia. Importing more solar and wind products means less opportunity to manufacture them here. And that means less opportunity for blue-collar workers, as well.

For inclusive economics, it can only mean one thing: promoting and supporting an economy that provides opportunities for more minorities. That is because, outside of Asian-Americans, the U.S. economy has a long way to go if it wants to look the way the White House wants.

U.S. JQI vs. Minority JQIs, 2007–2020. Black and Hispanic America Trailing Behind

CPA found what many would have suspected: Black American job quality is far worse than that of the total population. The Black Job Quality Index for 2020 was 38.7, whereas the average JQI for the total U.S. private-sector production and nonsupervisory workforce is in the 70s. For the Black nonsupervisory workforce, 72% of their jobs are low quality, paying less than the average worker in non-executive level paying positions.

More than any other group, Black Americans seem to be paying the price for the decline in U.S. job quality in recent decades, much of it due to a combination of automation, centralized online retail, and the offshoring of quality manufacturing jobs. They also end up getting more of the lower quality, often part-time jobs in restaurants and retail, as well.

Similar to the Black JQI, the JQI for Hispanic Americans was 38.1 in 2020, also less than half the U.S. JQI for all workers combined. In 2020, 28% of Hispanic American employees held high-quality jobs and 72% were in low-quality employment.

Although far below the U.S. average, the Hispanic American JQI actually rose 29% since 2007, when it was just 29.5. The increase in the Hispanic American JQI was driven largely by the growth of Hispanic jobs in higher-paying health care services and employment on construction sites.

We believe the best way for the job quality of both Black and Hispanics to rise on this index is to create more opportunities in high-quality manufacturing jobs.

See CPA’s Working Paper: Quantifying Job Quality for U.S., Black, Hispanic & Asian American Workers

The U.S. will reach a trillion-dollar trade deficit either in 2021 or 2022 due to our continued focus on Asian imports. The more manufactured goods we import, the less manufactured goods we make. The less we make, the higher the prevalence of low-quality employment, especially among Black and Latino workers.

Some Workforce Statistics

The JQI gathers data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) to come up with its indexes. Here’s a look at where Blacks and Hispanics constitute a greater percentage of the workforce than their percentage of the population.

According to the BLS, Black people make up 12.1% of the workforce. They are 14% of the population, though this includes children and retired people. In some manufacturing sectors, they are more prevalent on the factory floor than in society at large.

Black employees account for 17.7% of workers making household appliances. So if your Frigidaire refrigerator is made in Mexico now, that’s one less job in small towns like Evansville, Indiana, where around 13% of the population is Black and a Whirlpool factory closed there some 10 years ago.

In another example, after many years of shunning Black workers and city factories, as was the case in Detroit back in the 1960s, the auto industry has been a solid home for good-paying blue-collar workers who do not want to “learn to code”. Some 18.2% of auto manufacturing is comprised of Black staff, well above its portion of the working-age population.

Now think of the impact on the auto sector due to climate-related government policies. If the move to battery-powered vehicles means fewer parts (no more combustion engine), then it means fewer jobs. If you want to keep the auto sector a bellwether for middle-class Black families from Alabama to Michigan, then Washington will have to make it so EVs are made here.

The Ford Mach-E Mustang, an iconic American model, isn’t made here. It is made in Mexico. That’s good for Mexico; less good for Ohio and Michigan where Ford operates. Ford has 8 assembly lines in the U.S. It has seven in China, though most of that is for the Asian market. Ford has two factories in Mexico. Ford’s biggest manufacturing center is its Kentucky truck plant in Louisville. It has a staff of around 8,200. While we don’t know the percentage of Blacks and Hispanics in its workforce there, we do know that Louisville’s demographics are 23.6% Black. The Kentucky truck plant is an opportunity for everyone in Louisville that isn’t going to get rich as a YouTuber, or is an A+ STEM student on their way to Stanford.

Moreover, Lucid Motors, a new battery-powered automaker, recently built a new factory in Casa Grande, Arizona. Casa Grande is 43.7% Hispanic.

Here are where the overwhelming number of Black workers are employed in terms of their percentage of the workforce versus their working-age population:

Percentage of Workforce

Now for Hispanics.

According to the BLS, they account for 17% of the working-age population and make up 18% of the U.S. population today.

For the manufacturing sector, in particular, Hispanics constitute 24.4% of metallurgy work, 21.8% of glass manufacturing, 29.8% of concrete manufacturing, and 23.4% of aluminum manufacturing and processing. They also make up 24.1% of the furniture-making industry, an industry nearly wiped out by Chinese dumping a few years ago.

Hispanics are nearly a third of what is left of the American textile and apparel industry. We still do make clothes in the U.S. If not, the business would go to Central America and Asia and maybe some of those people would return to those countries. But many more who were born and raised here and have a life here would probably be forced into service sector jobs in their community.

Latinos are a massive part of America’s manufacturing base for both goods and non-durable goods. But the sectors of the U.S. economy where they dominate by nearly a factor of 2-to-1 are all low-end service work, much of it part-time:

The above table is for the non-executive workforce, so this does not include Latino owners of those companies, whom CPA assumes would be doing well economically.

Most minorities live in large urban centers where they dominate the services sector – whether it be public transportation or healthcare. Manufacturing largely exists outside of those urban centers, in smaller cities and towns nationwide.

CPA believes that building a more inclusive economy means creating blue-collar and so-called “new collar” jobs (derived from vocational training and apprenticeships, not four-year degrees) that lead to opportunities for Blacks and Hispanics outside of the crowded urban centers of the country.

The JQI Minority Index shows that one of the best ways to lift people up the economic ladder is to provide them with ample job opportunities outside of the urban service, and into the manufacturing sectors that do not always require a college education.

Recognizing that supply chains are complicated, Biden’s own plans to tackle the climate, for example, is one way to begin promoting the administration’s “inclusive economics” push and use the “green tech” space as a case example.

For Blacks and Hispanics, their lackluster representation in this segment of the U.S. economy has, in part, led to their much lower position on the Job Quality Index.

Manufacturing jobs not only pay better than the low-quality service sector jobs, they offer on the job training, better benefits, and a path for career advancement, which leads to improvements in socioeconomic status for individuals, families, and the communities where they live.

Increasing automation will hit all industries. Nevertheless, manufacturing companies have a vested interest in training and keeping their staff, where many service industries regard employees as disposable and interchangeable. If you want to build an inclusive economy, it starts with building things.

MADE IN AMERICA.

CPA is the leading national, bipartisan organization exclusively representing domestic producers and workers across many industries and sectors of the U.S. economy.

TRENDING

CPA: Liberty Steel Closures Highlight Urgent Need to Address Mexico’s Violations and Steel Import Surge

CPA Applauds Chairman Jason Smith’s Reappointment to Lead House Ways and Means Committee

Senator Blackburn and Ossoff’s De Minimis Bill is Seriously Flawed

JQI Dips Due to Declining Wages in Several Sectors as November Jobs Total Bounces Back from Low October Level

What Are Trump’s Plans For Solar in the Inflation Reduction Act?

The latest CPA news and updates, delivered every Friday.

WATCH: WE ARE CPA

Get the latest in CPA news, industry analysis, opinion, and updates from Team CPA.

CHECK OUT THE NEWSROOM ➔