By Jeff Ferry, CPA Research Director

General Motors is having a very good year in 2018. That’s right. You read that right, a good year. Maybe even an excellent year.

In Q3, its earnings performance knocked it out of the park. Wall Street was expecting earnings of $1.25 and the carmaker delivered $1.87. On the Oct. 31st conference call with investors, CEO Mary Barra was bullish on the full-year outturn, forecasting the company’s outcome this way: “We expect full-year EPS [earnings per share] to be at the top of our previously-communicated guidance range with potential for further upside..”

But, if you read the news, you might ask: didn’t GM announce the shutting of five auto plants in November, and the likely layoff of up to 14,000 workers in the US and Canada due to the tariffs? That’s drastic surgery. Isn’t GM hurting?

The fact is that the Nov. 26th cutbacks GM announced have little to do with its current sales, nothing at all to do with the tariffs, but a lot to do with the ongoing trend towards offshoring vehicle production to Mexico. GM is reducing its exposure to the small sedan market by shutting four US and one Canadian plant because those plants are operating well below capacity, in some cases at only 50 percent of full capacity. But in the past nine years, GM has increased its production in Mexico by 300,000. If even half of that production was allocated to the shutting US plants, those plants would likely be operating at profitable levels. Having ramped up its Mexican production faster than all of its rivals, GM is now the number two vehicle producer in Mexico and on its way to becoming number one.

It’s notable that the most popular model GM is axing, the Chevrolet Cruze, is produced at two plants: Lordstown, Ohio, and Ramos Arizpe, Mexico. The Lordstown plant is now slated for closure. GM is not closing Ramos Arizpe. The Mexican plant will be building the mid-size SUV Blazer, which hits the market next year. The last time GM sold Blazers was back in 2005, when they were produced at three GM plants, Moraine (OH), Linden (NJ), and Pontiac (MI). All those plants are now gone.

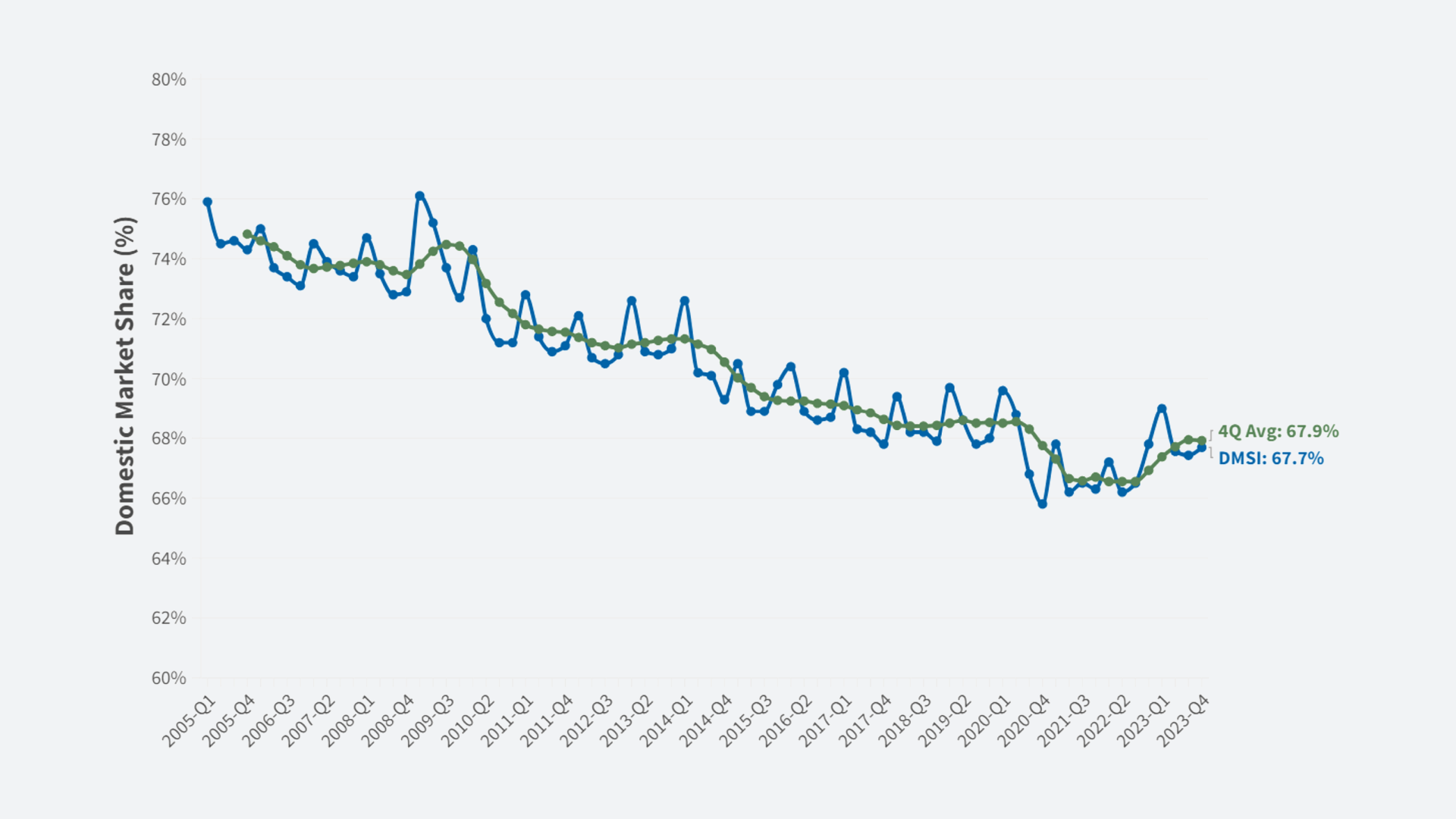

We compiled production figures from auto industry analysts Marklines to compare US production and Mexican vehicle production. All our data includes cars (including SUVs) and light trucks. Figure 1 shows that Mexican auto production has surged in the last nine years, up 85% over 2008.

|

Country |

Production 2008 |

Percent of NA Total 2008 |

Production 2017 |

Percent of NA Total 2017 |

Change 2008-2017 (%) |

|

USA |

7,050,012 |

63.3% |

9,680,594 |

61.9% |

37.3% |

|

Mexico |

2,043,574 |

18.3% |

3,773,569 |

24.1% |

84.7% |

|

Canada |

2,047,022 |

18.4% |

2,175,572 |

13.9% |

6.3% |

|

Total NA |

11,140,608 |

100% |

15,629,735 |

100% |

40.3% |

Figure 1: Mexico has gained 6 points of share of vehicle production from its northern neighbors in just nine years.

Figure 2 shows that along with Nissan, GM has been the most aggressive at ramping up production in Mexico. GM’s Mexican production is up by 300,000 units over the 2008 level. A look at Figure 3 shows that GM’s US vehicle production fell by some 330,000 units in 2017, while its production in Mexico rose by 126,000 last year. Ford is now the number one producer of vehicles in the US.

Figure 2. Nissan and GM have increased Mexican production aggressively.

Figure 3. It looks like GM production may have peaked in 2016 while Ford is now the number one producer of vehicles in the US.

With the closures announced last month, it’s likely that GM’s US production will continue to fall, while its Mexican production rises. If GM wasn’t loading up its Mexican plants, but instead shifted some of that production to the US facilities it’s planning to close, those facilities would be running at much higher levels of utilization and would probably be profitable.

GM is already highly profitable. CFO Dhivya Suryadevara boasted of $2.8 billion in profit in Q3 in North America alone (using the EBIT or earnings before interest and taxes definition of profit), a profit margin of 10.2 percent, up almost 2 points on the same period last year. The profit is driven mainly by pickup trucks, especially the new crew-cab models. GM’s average selling price in the quarter was a stunning $36,000, up $800 over the same period last year. Sales of high-end crew-cab trucks are running 30 percent above forecast, Barra told investors. As GM ditches its low-end sedan models, it is becoming increasingly a maker of high-end trucks for the American market.

Behind the Cutbacks: Mexico, SUVs, Trucks, Shareholder Value

The closures of the US and Canadian plants are not driven by a lack of profits, and they are certainly not driven by the steel and aluminum tariffs. Although the tariffs add a few hundred million dollars to GM’s costs, that additional cost is completely overshadowed by the additional revenue and profit flowing from better-than-expected truck sales.

No, the closures are driven by two fundamental forces: first, the continuing shift of American car-buying tastes away from sedans and towards trucks and SUVs. Secondly, they are driven by GM’s desire to move production out of the US, where auto workers earn some $30 an hour, and into Mexico, where they earn about $3 an hour. Underlying all of this is GM’s core philosophy, as explained to investors by CEO Barra: “I want to assure our owners that we are focused on creating shareholder value.”

The new USMCA deal negotiated by President Trump’s team promises minor improvements in industry incentives to produce in the US. Democrats in Congress and the United Auto Workers are likely to push in the new Congress to toughen up those rules, in particular by setting incentives for Mexican auto workers to get more workers’ rights and higher pay. President Trump and new Mexican President Lopez Obrador may turn out to be open to such reforms of the trade agreement. But even so, such reforms will take years to make a dent in the gap between costs in the US and Mexico.

Auto Tariffs

There is a way to provide additional incentives to US-based producers to produce more vehicles in the US: tariffs on auto imports into the US. The Department of Commerce has completed a study on this and while the study remains confidential, rumors say that it found a tariff on imported vehicles would be a viable solution to stimulate the US-based industry. A tariff is likely to have positive effects on US auto industry revenue, employment, profit and investment. GM sold its entire European business (to Peugeot) a year ago. The Big Three are more North America-focused than ever (if we ignore China, where the Communist government makes it near-impossible to produce internationally for the China market). A tax on non-North American imports would tend to favor GM, Ford, and Fiat-Chrysler.

The so-called “chicken tax” of 25 percent on imported light trucks has delivered a strong, highly profitable US truck business since its enactment in 1964. A similar tariff on imported cars could have a significant impact on our imports of $180 billion of vehicles last year. Since the new USMCA agreement will exclude Canada and Mexico from any tariffs, the two largest sources of imports are Japan ($41 billion) and Germany ($21 billion). GM North America’s revenue this year is likely to come in at around $110 billion, so if it could capture an additional $10 billion in revenue from the importers hit by tariffs, it would make a significant difference to its capacity utilization, profitability, and the viability of its US footprint.

Shareholder Value vs. Community Value and Long-Term Industry Value

There is a fundamental, philosophical question over how we reconcile the importance of the motor vehicle industry to the jobs and economic and social health of dozens of cities and towns across America with GM management’s focus on “shareholder value.” Today, this latter term is not just about maximizing short-term profit. Today’s stock market is in love with so-called “disruptive technologies.” In vehicles this means electric vehicles, self-driving vehicles, and “transport as a service.” GM is freeing up cash in order to invest in ambitious technology ventures. It’s doing this partly because these new paradigms may be the transport industry of the future. But it’s also doing this because the stock market puts higher valuations on the stock of any company that pursues these buzzword-y strategies.

History has shown that the way to succeed in many industries is to maintain a broad enough product line to generate the revenue and profit to fund new development. Shutting down a clutch of sedan models will help GM generate cash. But will shrinking the product line to generate cash to bet on new long-shot technologies ensure its long-term future? It’s a risky strategy.