The Post-World War II order, led by the United States, was designed to keep formerly warring nations from attacking each other again through treaties and tight economic cooperation. Economies were to be more interdependent. Global institutions would organize those commercial relations between nation-states.

It didn’t take long for that interdependence to become dependency. It started slowly in the 1980s with the early opening up of China. Then accelerated in the early 2000s with China’s ascension into the World Trade Organization.

From that time on, U.S. companies of all sizes have opted to source goods from China. As China got richer, smaller Asian markets became go-to hubs for new factories. E-commerce platforms are helping create a system where China businesses sell directly to U.S. consumers. The U.S. retail services industry is next to suffer from these lopsided trade balances.

In 2020, more than 8,300 US stores closed, following 9,300 in 2019, according to Insider analysis. Research firm Coresight predicts this trend will continue into 2021. The COVID-19 pandemic made online orders surge over the past year, but it wreaked havoc on brick-and-mortar retailers. Other retailers that didn’t close filed for bankruptcy, including J Crew, Nieman Marcus, and JCPenney. Even Disney closed 60 stores. Why not? Consumers can buy online and get it shipped direct from China. No need for physical stores, or retail workers.

This interdependence turned dependence will be a nightmare scenario should Washington ever need to yank the U.S. from China. Witness the dozens of multinationals like McDonald’s and Goldman Sachs who have, in just one week, shut down stores or left the Russian market with no plans of returning.

China isn’t storming the beach into Taiwan and may never do that. But the State Department says China is committing genocide in Xinjiang. Try and imagine Goldman Sachs and McDonald’s leaving China because of that. You can’t. It’s because the U.S. and China are too enmeshed. Leaving Russia is like pulling baby teeth. Leaving China is pulling four impacted wisdom teeth, plus two molars.

Many books have been written about how this all came about, and why it is still the lay of the land today. There are advantages and there are disadvantages.

For sure, one reason foreign companies want to manufacture in Asia is due to weaker environmental regulations, weaker currencies, and low labor costs.

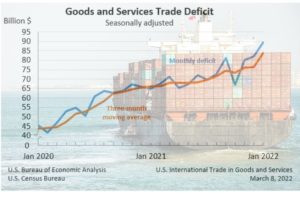

Earlier this week, the U.S. posted a nearly $90 billion global monthly trade deficit despite four years of tariffs on more than $250 billion worth of China goods. It was our highest monthly trade deficit on record. Our January deficit with China was around $33 billion – which is not the highest it has ever been on a monthly basis – but is showing no signs of any meaningful decline.

If supply chains have shifted out of China due to the trade war, they have largely gone to Vietnam, Thailand, and Malaysia, where their currencies are worth pennies to the dollar, or to Mexico, where the peso is another weak currency.

Meanwhile, China’s trade surplus with the world is near historical highs.

The U.S. goods trade deficit is at a historical high, hitting $1.09 trillion last year. It will hit $1.2 trillion this year, barring a worldwide recession.

Manufacturing jobs have declined as trade deficits rise, and soon retail jobs will decline thanks to the digital economy where one can shop for a living room set direct from Guangzhou instead of taking a stroll through a Crate & Barrel.

The global trade aficionados have lost the messaging, at least among the public. People believe the world favors powerful corporations, and have felt this way before wars and pandemics. Much of this is due to trade imbalances.

The International Trade Commission (ITC) last summer said large free trade deals like NAFTA had almost no positive impact on manufacturing labor and had negative impacts among Black blue-collar workers and women who didn’t “learn to code” in college.

Trade volume has gone up, of course, but the U.S. has become an even bigger dumping ground for overproduction, primarily from Asia.

The result is American de-industrialization, income insecurity, and national insecurity. Try and imagine the consequences if China invaded Taiwan as Russia did Ukraine. Or, even more probable, in a deepening rift with Washington, Beijing retaliates against tariffs and restrictions by banning U.S. companies there. China would have a free army of lobbyists in Washington arguing on their behalf, without having to spend one penny to convince them to do so. This is due to our enmeshed ties to China, where interdependence has become a dependency that has not only hamstrung U.S. businesses but also makes it harder for U.S. policymakers to change rules as they relate to China.

As it is now, the White House has no appetite to go after China via secondary sanctions for its financial support of sanctioned Russian companies.

A dozen years or so after Adam Smith published Wealth of Nations…George Washington and Alexander Hamilton presented a different vision of economic statecraft. For them, the development of domestic manufacturing capacity was a national security imperative. America was isolated geographically, and vulnerable to embargoes. The United States, they decided, would have to become economically self-sufficient to guarantee its newfound political independence. As Washington put it in an address to Congress on January 8, 1790: “A free people ought not only be armed but disciplined. Their safety and interest require that they should promote such manufactures as tend to render them independent of others for essential supplies.” –excerpted from “Trade Wars are Class Wars” by Matthew C. Klein and Michael Pettis

Most everyone is impacted by the Russia-Ukraine war. Commodity prices will rise and fall on market readouts of cease-fire talks. Oil prices are leading to higher gasoline prices. Washington is using this as a partisan fight to make the case for more fossil fuel production or a faster rollout of EVs and renewables.

There is an example of American dependence in this partisan divide over energy: as the White House promotes a non-fossil fuel economy as being less dependent on foreign sources, recall February 4 when the White House went against the ITC’s recommendation to extend tariffs on solar panels used by electric power utilities. This was a gift to importers. The makers of these solar panels are almost 100% Chinese. The ending of those solar safeguards means more dependence on a foreign source for solar, not less.

China is still allowing companies to set up shop at home to cater almost exclusively to the U.S. For big items deemed strategically important, like solar and wind, and battery materials, for example, Beijing is still subsidizing its exporters.

Chinese authorities believe their latest macroeconomic policy measures will stabilize local companies recovering from the pandemic and support economic growth as the locals save instead of spend.

According to the China state press, government policy measures to support exporters mean “continued expansion and improvements in the structure and quality of China’s foreign trade.” Beijing says this will help global supply chains and a world economic recovery.

It will help global supply chains – if those global supply chains are okay with everything being tied to China.

Years ago, someone said that “when China sneezes, the world catches a cold.” Our 23 months in a pandemic showed exactly that, quite literally. But the impact goes beyond temporary health woes; it also led to supply chain breakdowns due to overreliance on Asian markets. How much longer can the U.S. economy put up with these imbalances?

When foreign policy specialists discuss the rise of Asia, it is because of China, not Japan, not Russia’s oil and gas-rich far east. It’s not the old Asian Tigers. China rises because Beijing will accelerate export tax rebates, increase export credit support, and improve export credit insurance to keep its mercantilist economy going.

It is true that U.S. consumers benefit from Chinese subsidies, but this is hardly a good thing in a country suffering from over-consumption. This benefit comes with a huge cost. The real dispute is over trade and trade is a question of employment and debt, not about how one country helps another country consume.

In 2013, Michael Pettis wrote in his book “The Great Rebalancing” that the world will rebalance trade one way or the other. That will mean less dependence. It might mean a much weaker dollar.

“Any policy that does not clearly result in a reversal of the deep debt, trade and capital imbalances of the past decade is a policy that cannot be sustained,” Pettis wrote. “The goal of policymakers must be to work out what rebalancing requires and then to design and implement the least painful way of getting there.”

“Successful nations are the ones that run persistent trade surpluses,” said CPA chief economist Jeff Ferry. “They don’t need to be very large, just large enough to allow the manufacturing industry to expand and enjoy the tailwind of growth and economies of scale. But unsuccessful economies are the ones that run chronic deficits and use artificial means to stimulate consumption. That always ends in tears.”

Post-WWII Interdependence Has Led to Too Much Dependence

The Post-World War II order, led by the United States, was designed to keep formerly warring nations from attacking each other again through treaties and tight economic cooperation. Economies were to be more interdependent. Global institutions would organize those commercial relations between nation-states.

It didn’t take long for that interdependence to become dependency. It started slowly in the 1980s with the early opening up of China. Then accelerated in the early 2000s with China’s ascension into the World Trade Organization.

From that time on, U.S. companies of all sizes have opted to source goods from China. As China got richer, smaller Asian markets became go-to hubs for new factories. E-commerce platforms are helping create a system where China businesses sell directly to U.S. consumers. The U.S. retail services industry is next to suffer from these lopsided trade balances.

This interdependence turned dependence will be a nightmare scenario should Washington ever need to yank the U.S. from China. Witness the dozens of multinationals like McDonald’s and Goldman Sachs who have, in just one week, shut down stores or left the Russian market with no plans of returning.

China isn’t storming the beach into Taiwan and may never do that. But the State Department says China is committing genocide in Xinjiang. Try and imagine Goldman Sachs and McDonald’s leaving China because of that. You can’t. It’s because the U.S. and China are too enmeshed. Leaving Russia is like pulling baby teeth. Leaving China is pulling four impacted wisdom teeth, plus two molars.

Many books have been written about how this all came about, and why it is still the lay of the land today. There are advantages and there are disadvantages.

For sure, one reason foreign companies want to manufacture in Asia is due to weaker environmental regulations, weaker currencies, and low labor costs.

Earlier this week, the U.S. posted a nearly $90 billion global monthly trade deficit despite four years of tariffs on more than $250 billion worth of China goods. It was our highest monthly trade deficit on record. Our January deficit with China was around $33 billion – which is not the highest it has ever been on a monthly basis – but is showing no signs of any meaningful decline.

If supply chains have shifted out of China due to the trade war, they have largely gone to Vietnam, Thailand, and Malaysia, where their currencies are worth pennies to the dollar, or to Mexico, where the peso is another weak currency.

Meanwhile, China’s trade surplus with the world is near historical highs.

The U.S. goods trade deficit is at a historical high, hitting $1.09 trillion last year. It will hit $1.2 trillion this year, barring a worldwide recession.

Manufacturing jobs have declined as trade deficits rise, and soon retail jobs will decline thanks to the digital economy where one can shop for a living room set direct from Guangzhou instead of taking a stroll through a Crate & Barrel.

The global trade aficionados have lost the messaging, at least among the public. People believe the world favors powerful corporations, and have felt this way before wars and pandemics. Much of this is due to trade imbalances.

The International Trade Commission (ITC) last summer said large free trade deals like NAFTA had almost no positive impact on manufacturing labor and had negative impacts among Black blue-collar workers and women who didn’t “learn to code” in college.

Trade volume has gone up, of course, but the U.S. has become an even bigger dumping ground for overproduction, primarily from Asia.

The result is American de-industrialization, income insecurity, and national insecurity. Try and imagine the consequences if China invaded Taiwan as Russia did Ukraine. Or, even more probable, in a deepening rift with Washington, Beijing retaliates against tariffs and restrictions by banning U.S. companies there. China would have a free army of lobbyists in Washington arguing on their behalf, without having to spend one penny to convince them to do so. This is due to our enmeshed ties to China, where interdependence has become a dependency that has not only hamstrung U.S. businesses but also makes it harder for U.S. policymakers to change rules as they relate to China.

As it is now, the White House has no appetite to go after China via secondary sanctions for its financial support of sanctioned Russian companies.

Most everyone is impacted by the Russia-Ukraine war. Commodity prices will rise and fall on market readouts of cease-fire talks. Oil prices are leading to higher gasoline prices. Washington is using this as a partisan fight to make the case for more fossil fuel production or a faster rollout of EVs and renewables.

There is an example of American dependence in this partisan divide over energy: as the White House promotes a non-fossil fuel economy as being less dependent on foreign sources, recall February 4 when the White House went against the ITC’s recommendation to extend tariffs on solar panels used by electric power utilities. This was a gift to importers. The makers of these solar panels are almost 100% Chinese. The ending of those solar safeguards means more dependence on a foreign source for solar, not less.

China is still allowing companies to set up shop at home to cater almost exclusively to the U.S. For big items deemed strategically important, like solar and wind, and battery materials, for example, Beijing is still subsidizing its exporters.

Chinese authorities believe their latest macroeconomic policy measures will stabilize local companies recovering from the pandemic and support economic growth as the locals save instead of spend.

According to the China state press, government policy measures to support exporters mean “continued expansion and improvements in the structure and quality of China’s foreign trade.” Beijing says this will help global supply chains and a world economic recovery.

It will help global supply chains – if those global supply chains are okay with everything being tied to China.

Years ago, someone said that “when China sneezes, the world catches a cold.” Our 23 months in a pandemic showed exactly that, quite literally. But the impact goes beyond temporary health woes; it also led to supply chain breakdowns due to overreliance on Asian markets. How much longer can the U.S. economy put up with these imbalances?

When foreign policy specialists discuss the rise of Asia, it is because of China, not Japan, not Russia’s oil and gas-rich far east. It’s not the old Asian Tigers. China rises because Beijing will accelerate export tax rebates, increase export credit support, and improve export credit insurance to keep its mercantilist economy going.

It is true that U.S. consumers benefit from Chinese subsidies, but this is hardly a good thing in a country suffering from over-consumption. This benefit comes with a huge cost. The real dispute is over trade and trade is a question of employment and debt, not about how one country helps another country consume.

In 2013, Michael Pettis wrote in his book “The Great Rebalancing” that the world will rebalance trade one way or the other. That will mean less dependence. It might mean a much weaker dollar.

“Any policy that does not clearly result in a reversal of the deep debt, trade and capital imbalances of the past decade is a policy that cannot be sustained,” Pettis wrote. “The goal of policymakers must be to work out what rebalancing requires and then to design and implement the least painful way of getting there.”

“Successful nations are the ones that run persistent trade surpluses,” said CPA chief economist Jeff Ferry. “They don’t need to be very large, just large enough to allow the manufacturing industry to expand and enjoy the tailwind of growth and economies of scale. But unsuccessful economies are the ones that run chronic deficits and use artificial means to stimulate consumption. That always ends in tears.”

MADE IN AMERICA.

CPA is the leading national, bipartisan organization exclusively representing domestic producers and workers across many industries and sectors of the U.S. economy.

TRENDING

CPA: Liberty Steel Closures Highlight Urgent Need to Address Mexico’s Violations and Steel Import Surge

CPA Applauds Chairman Jason Smith’s Reappointment to Lead House Ways and Means Committee

Senator Blackburn and Ossoff’s De Minimis Bill is Seriously Flawed

JQI Dips Due to Declining Wages in Several Sectors as November Jobs Total Bounces Back from Low October Level

What Are Trump’s Plans For Solar in the Inflation Reduction Act?

The latest CPA news and updates, delivered every Friday.

WATCH: WE ARE CPA

Get the latest in CPA news, industry analysis, opinion, and updates from Team CPA.

CHECK OUT THE NEWSROOM ➔