Editors’ note: This is an important and clear article by respected journalist Matthew Klein supporting the Baldwin/Hawley Competitive Dollar for Jobs and Prosperity Act. However, CPA does not want to “forget tariffs” because they are essential to address trade cheating, to conduct industrial policy to improve the composition of trade, and to address bad actor countries like China.

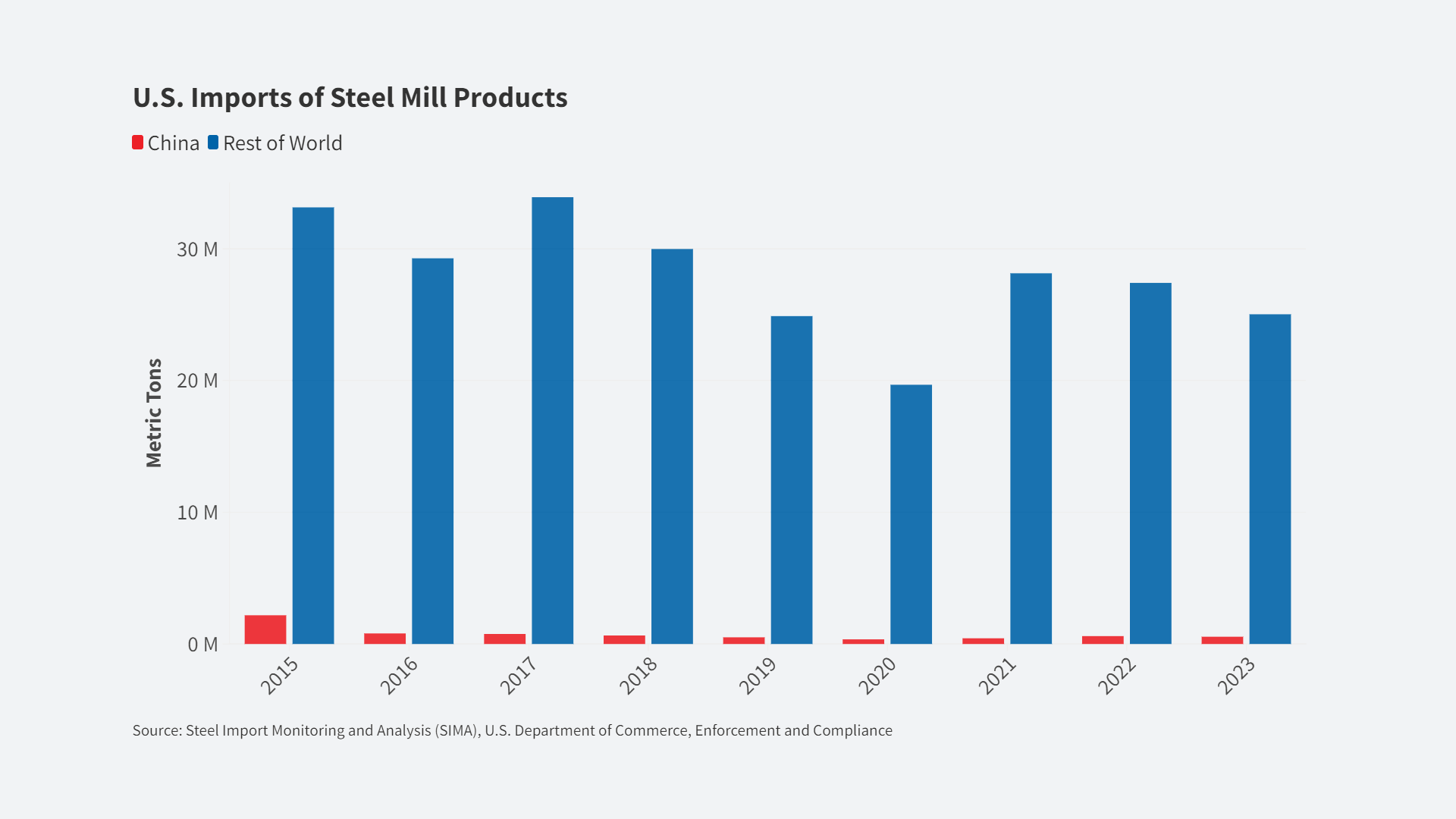

While the current trade dispute between the U.S. and China dominates the news, America’s trade problems—with a wide range of countries—date to the early 1980s. Diplomacy and tariffs have failed repeatedly, even when negotiating with allies, and there is little reason to think they will work this time.

[Matthew C. Klein | August 9, 2019 | Barrons]

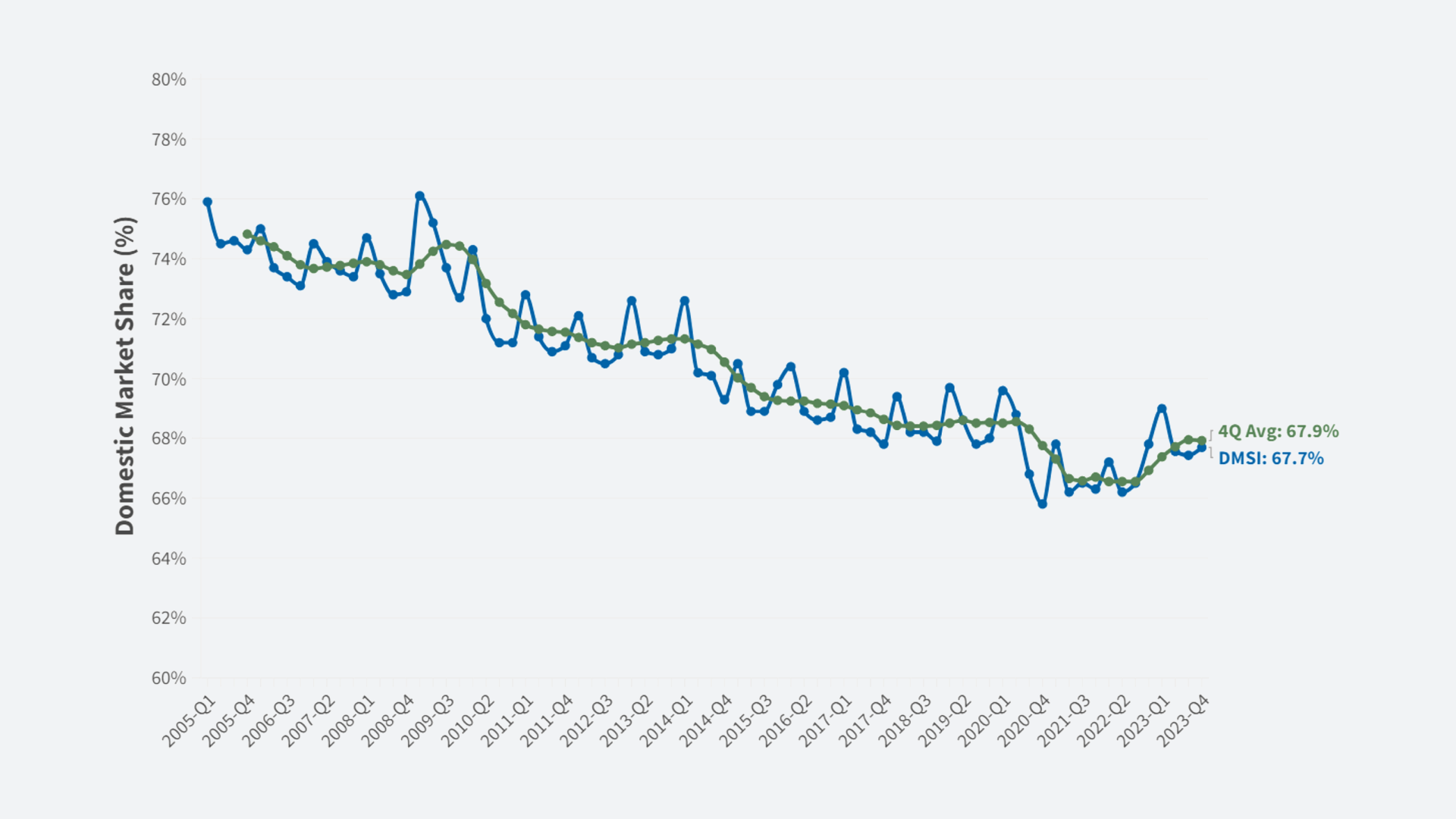

For nearly four decades, Americans have been consistently spending more than they earn. This is not because Americans have been living large—average spending on consumption and investment grew at the same stable rate from 1947 through 2006—but because people in the rest of the world have been living below their means. Foreigners have been consuming less than they produce and dumping the excess into the U.S. market, displacing American output.

The resulting trade deficits have destroyed U.S. jobs and forced U.S. consumers to replace the lost income with debt. Unfortunately, the measures taken so far have done little to resolve the underlying problems. The U.S. trade deficit continues to widen, while China’s trade surplus has grown over the past year, thanks to dwindling demand for imports from the rest of the world. As Barron’s argued last year, “Tariffs will not fix anything as long as China’s elites remain committed to extracting as much as they can from Chinese workers.”

One obvious problem, clearly demonstrated over the past week, is that tariffs can easily be offset by depreciating a currency. China can cheapen the yuan to make its exports less expensive for Americans and to further discourage imports from the rest of the world. (It’s important to note that China is not the only, or even the biggest, contributor to global imbalances. Europe is currently a far greater drag on the global economy and, by extension, the greater threat to U.S. jobs.)

The Baldwin-Hawley bill aims to address these defects. The proposal would require the Federal Reserve to keep America’s current account—the difference between national income and national spending—balanced around zero over five-year periods. More specifically, the central bank would have to determine the level of the U.S. dollar needed to balance income and spending, after which it would have to adjust the exchange rate accordingly.

That level would be far lower than it is today. As Joe Gagnon, formerly one of the Fed’s top economists focusing on international affairs and currently an expert at the nonpartisan Peterson Institute for International Economics, put it to me, “The dollar tends to fluctuate between being too high and being about right, but it has never been too low.” The reason is that foreign savers disproportionately prefer to store their wealth in the U.S., thanks to the size of its market and the quality of its legal protections for investors.

Excess savings from abroad have simultaneously financed and caused America’s trade deficits by inflating the value of the dollar. Persistent overvaluation has destroyed U.S. jobs and forced Americans to borrow from abroad to compensate for the lack of income.

While it is fashionable in certain quarters to argue that exchange rates have little effect on trade patterns, the data clearly show a relationship between changes in the real value of the dollar and changes in America’s current account balance. In general, a sustained 10% move in the dollar translates to a roughly one percentage point change over time in the U.S. current account balance relative to gross domestic product.

Currently, the Fed cannot simultaneously manage the value of the dollar, keep inflation under control, and stabilize the swings in the business cycle. The bill therefore provides the Fed with two additional tools to manage the exchange rate.

First, and most important, is the “market access charge,” which would require foreign savers to pay a tax each time they want to invest in the U.S. The charge would be applied only to new purchases of U.S. assets, and it wouldn’t be a recurring fee on existing holdings. The Fed would have the discretion to determine the appropriate level of the charge to bring the dollar toward its appropriate level and adjust it as necessary.

This may seem controversial, but other countries have used similar tools in the recent past to avoid unwanted inflows. The International Monetary Fund has endorsed “capital flow management measures” as legitimate policy instruments in a variety of cases, especially when the currency is overvalued. Australia, Brazil, and South Korea have all imposed taxes and quantitative restrictions on various kinds of foreign investments, including bank loans, currency derivatives, and housing. All have received the IMF’s blessing. The proposed market access charge would be a simpler and more comprehensive version.

However, it would deter only profit-seeking investors, such as Dutch pension funds or Taiwanese insurers. The market access charge wouldn’t discourage government agencies such as the Swiss National Bank or the People’s Bank of China from intervening in the foreign-exchange markets.

The bill therefore gives the Fed the additional authority to buy as many foreign assets as necessary to offset unwanted inflows. (Currently, the power to intervene in the currency markets resides with the U.S. Treasury and is limited.) In theory, this could be a powerful supplementary tool, although it would be limited by the openness and the size of the target markets.

The ideal solution to America’s trade deficit would be for people in the rest of the world, particularly Europe and East Asia, to spend more on themselves. They could buy more of what they produce and export less, they could buy more from others and import more, or both. At a time of low inflation, low interest rates, and ample spare capacity, any of those options would raise living standards globally, including in the U.S. Failing that, Americans should be prepared to act unilaterally by deterring unwanted financial inflows.

Support the Competitive Dollar for Jobs and Prosperity Act. Sign Here