Key Points

- The 2018-2023 washing machine tariffs led to a larger, more competitive U.S.-based residential washer industry, including the creation of over 2,000 new jobs at two Korean-owned companies which opened U.S. manufacturing facilities in the southern U.S.

- Washing machine prices are now below pre-tariff levels, and prices have risen less than consumer inflation, demonstrating that after a six-month flurry, tariffs had little to no effect on washing machine prices.

- The success of the washing machine tariffs shows that “tariff-jumping investment,” i.e. inducing domestic industry growth via tariffs is a viable strategy for the U.S. in industries that have suffered decline.

In January 2018, President Donald Trump imposed tariffs of 20% to 50% on large residential washing machines. The tariffs expired in February 2023. Six years later, we can make an assessment: the tariffs created over 2,000 jobs and provided economic growth for the two communities where Korean appliance makers built factories. They also provided economic support for Whirlpool, the leading U.S.-headquartered appliance maker and employer of 23,000 Americans, as well as GE Appliances, which is today Chinese-owned and employs 16,000 Americans at Louisville, Kentucky and other facilities.

Further, washing machine prices, which temporarily surged in the first half of 2018, came back to earth in 2019 and have continued to rise significantly less than inflation since. Tariff opponents in the media and the academic economist community continue to repeat the falsehood that tariffs raised washing machine prices when over any timeframe other than a few months, tariffs have had no visible impact on washing machine prices.

In 2013, the Obama administration imposed tariffs on imported washing machines from South Korea. This led the Korean producers to shift production for the U.S. market to China, which led to another anti-dumping investigation by the U.S. International Trade Commission. That investigation published a finding in December 2016 that Chinese washing machines benefited from subsidies (“anti-dumping margins” in the formal lingo) of 44.28% and recommended duties at that level. The Trump administration, with U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer as the driving force, decided instead to impose global duties or tariffs on all imported large residential washing machines, whatever their source. The duties, imposed in January 2018, started at 20% and once the quota of 1.2 million imported washers was reached, rose to 50%.

For years, the two large importers, Samsung and LG Electronics, had opposed any import restrictions. But once those tariffs were in place, the Korean manufacturers quickly changed their tune.

In 2018, LG Electronics completed an investment of $360 million in a new “smart factory” in Clarksville, Tennessee. LG hired 700 employees and began building washing machines there. In April 2021, it announced that it had produced 1 million washing machines at Clarksville. It said it was investing a further $20.5 million and hiring 300 more employees, to bring its Clarksville headcount to “about 1,000.” In December 2022, LG announced three new model washing machines capitalizing on the trend towards energy-efficient and “smart” (i.e. Internet-enabled) appliances. Those new models are all to be made in Clarksville.

Buck Dellinger, CEO of the Clarksville Industrial Development Board, told us that LG Electronics is one of a number of large companies that have chosen to build facilities in the Clarksville industrial park. Clarksville set up the industrial park 22 years ago to build up an industrial base to offer alternative employment in case the nearby Fort Campbell army base reduced its presence in the area. In the last five years, the industrial park has added 4,514 direct jobs, and a total of 7,236 including indirect jobs, Dellinger said. Indirect jobs include suppliers to the companies in the industrial park, and service companies serving employees such as restaurants and convenience stores. In the ten years to 2022, Clarksville’s average salary grew 77%, as compared to the U.S. growth rate of 62%. With 177,000 residents, Clarksville is adding population at over 3% a year and is now Tennessee’s fifth largest city, right behind Chattanooga.

“We’re ecstatic to have LG Electronics in the region,” said Buck Dellinger. “Advanced manufacturing helps to give us low unemployment, a high workforce participation rate, and a young workforce.” Dellinger recently returned from a trip to South Korea where he met with LG executives. “They are a very stable company, and take good care of their employees. They have enough land here to quadruple their operation and we hope they do.”

It’s a similar story in Newberry, South Carolina, where Samsung built an appliance facility in 2018. In 2017, recognizing that the Trump administration was determined to clamp down on washer imports, Samsung announced plans to invest $350 million to build a manufacturing facility in Newberry, South Carolina with 1,000 employees. In 2020, Samsung invested an additional $120 million to expand the facility, which now employs 1,200.

Newberry is a smaller, more rural and agricultural area than Clarksville. Located 40 miles northwest of Columbia, Newberry County’s population is just 38,000. Samsung is one of only two manufacturers in the county with more than 1,000 employees. The other is a food processing company. As a relatively high-tech appliance manufacturer that designs as well as manufactures products, Samsung has had a significant impact on business, jobs, and prosperity in Newberry County. According to a local news report last October, the “Samsung effect” in Newberry has contributed to investment in new housing developments, new restaurants and other new businesses in the area. The report quoted John Worthington, Executive Chef at local restaurant Figaro the Dining Room, who said: “with these bigger corporations like Samsung coming in, they’re bringing in good-paying jobs which makes the economy and the town better.” Figaro is currently advertising for employees.

Consumer Prices

The greatest myth about tariffs is that they lead directly to a one-for-one increase in consumer prices of the tariffed goods. The price effect of tariffs depends on the competitive dynamics of the industry that is tariffed, the weight of the level of imports in domestic consumption, and other variables. The U.S. International Trade Commission found in a detailed study published last year that across a range of industries, the various tariffs imposed by the Trump administration led to price increases in the domestic market for the tariffed goods worth between 10% and 20% of the headline rate of tariff. In other words, a 25% tariff would lead to U.S. price increases in the tariffed sector of between 2.5% to 5%. We summarized that study’s findings here.

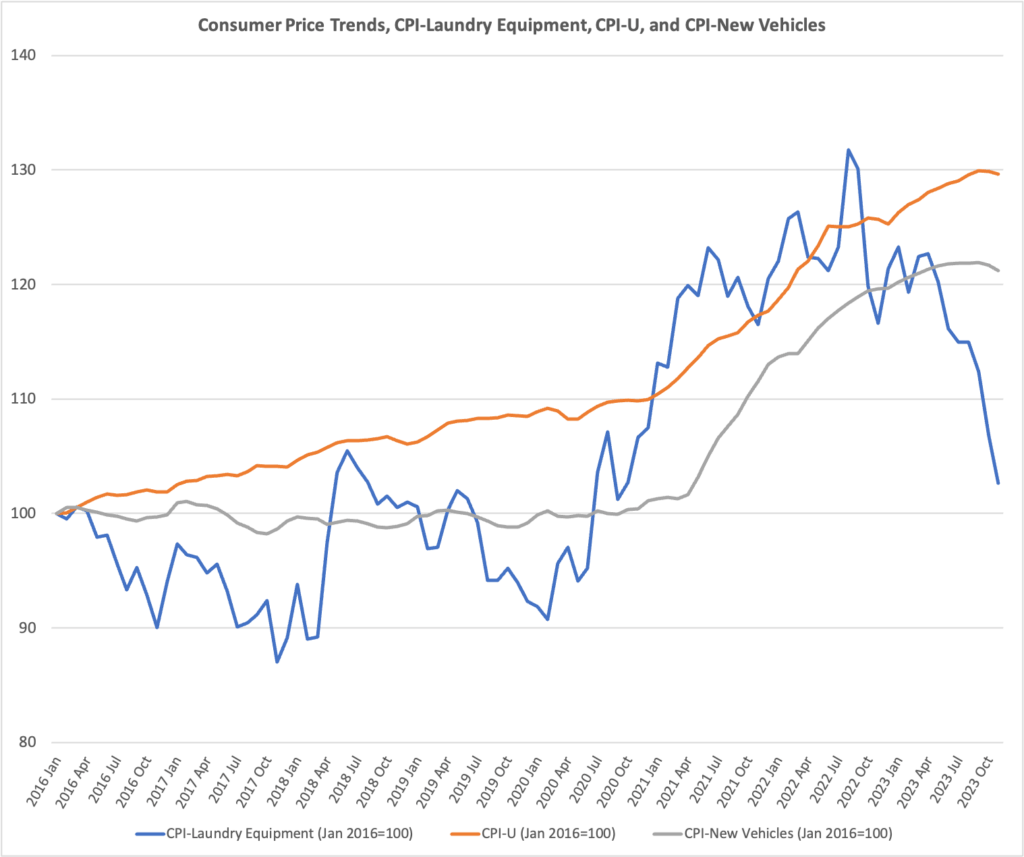

The market reactions to the 2018 tariffs on residential washers was typical of another trend often observed after tariff imposition. In early 2018, washing machine prices shot up as the market, fearing high prices and potential shortages, sought to build up inventories. Between January 2018, when the tariffs were imposed, and June, the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ price index for laundry equipment rose by 12.4%, a large jump. However in the next 14 months, the index tumbled by 10.7%, until it was at almost the same level (91.1) as it was in January 2018. In short, sanity returned to the market, and all participants, from the manufacturers to the distributors to the retailers, saw that the tariffs would have almost no effect on the U.S. retail price for washers.

Table 1 tells the story. We look at three key price indicators, the consumer price index for laundry equipment, the index for new auto vehicles, and the broad consumer price index for all goods and services, known by its BLS acronym CPI-U. We compare the price changes between January 2018, the month when washer tariffs became effective, and two years later, January 2020, right before the Covid pandemic and shutdown began to impact prices and production.

Over this two-year timeframe, the broad CPI rose by 4.1%, the new vehicle index inched up by just 0.2%…and the laundry equipment index fell by 2.1%! During this time, the residential washer industry (roughly half of total laundry equipment) had a tariff imposed on it of 20% to 50%, while the new vehicle industry had no new tariffs imposed on it (Chinese vehicles did have new tariffs, but they were and are a trivial part of U.S. imports). Most imported new vehicles pay a tariff of 2.5%, except those from Canada and Mexico which come in duty-free. And yet, new vehicle prices rose more than laundry equipment prices!

Table 1. Washing machine prices fell slightly in the two years after tariff imposition.

| Sector | Price Index Jan 2018 | Price Index Jan 2020 | % change | % change, annual rate |

| Consumer Price Index (CPI-U) | 247.867 | 257.971 | 4.1% | 2.0% |

| Consumer prices-laundry equipment | 90.708 | 88.843 | -2.1% | -1.0% |

| Consumer prices-new vehicles | 146.996 | 147.253 | 0.2% | 0.1% |

| Notes: CPI-U is BLS code CUUR0000SA0; CPI-Laundry equipment is CUSR0000SS30021. New vehicles is CUUR0000SETA01. | ||||

Clearly, tariffs play a minor role in price movements for laundry equipment, as for most other goods tariffed by the Trump administration. Tariffs do of course add to the cost of imported manufactured goods. But prices charged to consumers are determined by many factors and tariffs tend not to be high on the list. In an oligopolistic, branded-goods industry like residential washers, where there are only a handful of competitors in the mass market, hitting sales targets and increasing market share tend to be more important than short-term profitability. In other words, for a competitive company, be it domestic like Whirlpool, or imported like Bosch, or imported-transformed-into-domestic like Samsung, holding onto market share is often the most important corporate objective. Another critical objective is maintaining the loyalty of the vital channel to the consumer, which includes large retailers like Home Depot. Winning floor space at Home Depot, and maintaining consumer loyalty, can be badly disrupted by a sudden price increase, whether it can be blamed on tariffs or any external factor.

In the long term, businesses must recover all their costs and tariffs, if permanent, can influence prices. But in the short to medium term, especially when there are numerous domestic competitors in the market, competition will often prevent companies from raising prices to recover tariff costs.

In April 2019, two University of Chicago economists and one Federal Reserve economist published a study[1] on washing machine prices after the 2018 tariff which found that the tariffs caused an 11% increase in the price of washers, and, strangely, a similar increase in the price of dryers (which were not tariffed). Unsurprisingly, the authors chose a narrow period of pricing data to look at, specifically those months when washer price levels were at their highest. Here is their conclusion, in their own words: “…the price of washers jumps by around 11 percent in the period four to eight months following the application of these tariffs.”[2] The authors do not explain why they chose a “four to eight” month period to study. The obvious conclusion is that this is the period for which their regression equations generated the largest tariff-related price increase.

The CPI for laundry equipment peaked at 102 in June 2018. By December 2019, it was down to 89.3, slightly below the pre-tariff level of 90.7 in January 2018. So the Flaaen, Hortacsu, Tintelnot article was effectively obsolete eight months after its April 2019 publication.

That has not stopped the many tariff opponents in the mainstream media from citing the article as evidence that tariffs raised washer prices[3]. None of these media outlets has to our knowledge, revisited the topic to attempt to understand why washer prices fell so rapidly after their rise in the first half of 2018. On the contrary, they have continued to tell and re-tell the fiction of tariffs causing double-digit washer price rises. As recently as January 2024, the Wall Street Journal cited the Flaaen, Hortacsu, Tintelnot’s “11.5%” rise in washer prices in mid-2018 without noting that the number was obsolete by the end of 2019.

Many readers will dismiss such studies and media coverage as simply further evidence of the anti-tariff bias of the academic economics community and the mainstream media. Yet for economists, I believe the problem is deeper than that. For at least half a century, U.S. academic economists have been focused on building crudely simplified models that can hold true across decades and across many industries, essentially by leaving out many important variables and making broad unrealistic assumptions. They then endeavor to “validate” those models with statistical analysis. This simplistic approach was largely pioneered by MIT economist Paul Samuelson, who christened such models “toy models.” The use of “toy models” and statistical analysis gives academic economics a bias towards simplistic, unrealistic conclusions based not on genuine knowledge of how industry works but instead on clever manipulation of statistics and data to prove seemingly generalized, but largely fictional, results.

In 2020, economist and Nobel laureate George Akerlof published “Sins of Omission and the Practice of Economics”,[4] an article highly critical of the economics profession, arguing that most economists are too divorced from the real world. “Only 3 percent of economists thought it `very important’ for their success to `have a thorough knowledge of the economy’,”[5] he wrote, citing an earlier poll of economics graduate students. He said “Economics PhD. programs are trying to train students to become productive researchers, not to teach them about the economy.”[6] “Research” in this context means primarily statistical studies with powerful modern computers where almost any proposition can be validated by carefully selecting the variables and time periods that go into the analysis. Akerlof advocated an overhaul of the teaching of economics and the processes by which the most influential academic journals select and edit articles as steps to bring economics back to contact with the real world and understanding the forces driving our economy. So far, his critique has been largely ignored.

Industrial economics is one area that has suffered badly from the rise of the “toy model” approach. Its heyday was the 1920s and the study of individual industries has declined consistently since then. Economists today generally know little of how industry really works and refuse to learn. Figure 1 below shows the evolution of prices for laundry equipment, new vehicles, and the broad CPI-U from 2016 to November 2023. It can be seen clearly that laundry equipment prices are much more volatile than the other two variables. The price volatility is likely related to the decisions of distributors to build or reduce inventory in response to ever-changing expectations of sales or product availability. Further the price rises that began in 2020 show that the Covid pandemic, by making it difficult and unpredictable to source parts or products from across the Pacific, unleashed much greater price increases than anything related to tariffs.

Figure 1. Laundry equipment prices fell in the two years after tariffs were imposed, while the CPI and the price index for new vehicles both rose in that period.

Tariff-Jumping Investment

Finally, it should be noted that by incentivizing both LG Electronics and Samsung to open and then expand manufacturing facilities in the U.S., the U.S. achieved the best of both worlds: the tariffs led to the creation of more U.S.-based competitors, with more jobs, more competition, and more product innovation done here, while only a minority of washers purchased here were affected by tariffs.

Economists in the developing world have a phrase for this phenomenon: tariff-jumping investments. For developing countries, with large domestic markets, high tariffs can be an effective means of incentivizing international companies to locate production within a country’s borders. Badri Narayanan, currently a Fellow and formerly the Head of Trade and Commerce at prime minister Narendra Modi’s policy planning think tank NITI Aayog, and an Affiliate Professor at Boston College, points out that high tariffs on automobiles, combined with low tariffs on auto parts and investment liberalization, has enabled India to build a large and successful domestic automotive industry that is truly global. In 2022, global auto trade association OICA figures show India built 5.46 million vehicles, ranking fourth in the world, ahead of Germany and South Korea.

The same principle can apply to the U.S., which although not a developing country, has lost much of its industrial base. Today, the U.S. has a larger, more successful, and more competitive residential washer industry thanks to the tariffs.

The goal of industrial policies like targeted tariffs should be to build domestic industries to create growth, investment, employment, and an upward trend in worker incomes. Of the two major domestic manufacturers, Whirlpool recently reported modest (1%-2%) growth in its domestic market and is exiting foreign markets. In recent reports it stressed to investors that its goal is to rein in costs to achieve 10% earnings margins. (As a subsidiary of a Chinese multinational, GE Appliance reports no financial figures, making it hard to judge its economic performance.) It would not be surprising if either of these companies reduced staffing levels in the coming years. But employment count is not the critical metric. It’s more critical to have enough companies and competition so the more successful companies are creating jobs even if others are losing, and the industry as a whole remains healthy. That has positive effects for the upstream and downstream industries that supply the appliance industry and for the economy as a whole.