The foreign exchange value of the U.S. dollar is soaring on an almost daily basis, causing problems here at home and abroad. There is growing talk of international coordination to stem the rise of the dollar and bring more stability to currency markets. Meanwhile there is support in Congress for the CPA proposal of a Market Access Charge to moderate the flood of incoming capital flows and move the dollar back down towards a more competitive level.

So far, Biden administration officials are like the three monkeys: they see nothing, hear nothing, and say nothing. But the pressure to act may soon become irresistible.

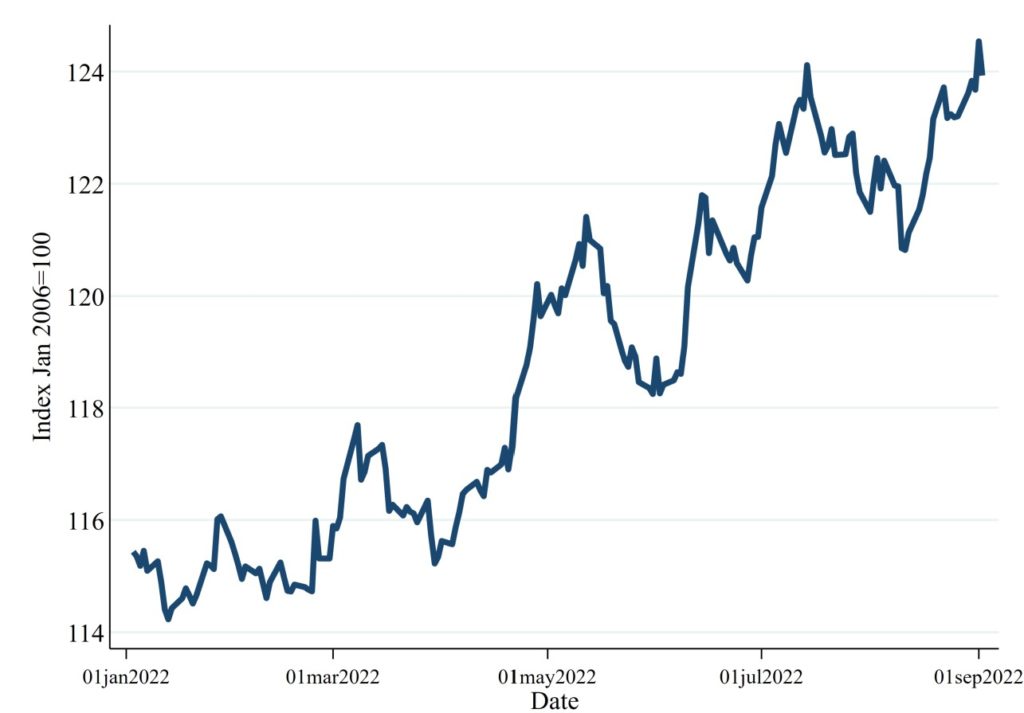

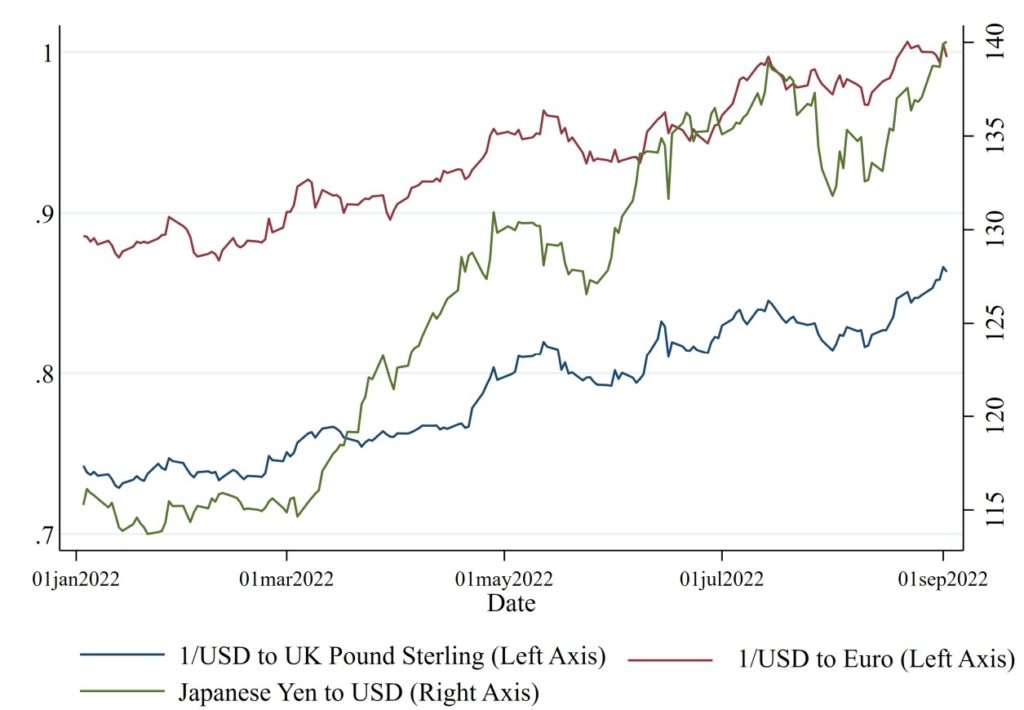

Since the start of this year, the dollar has risen 7.4% on a trade-weighted basis (see Figure 1 below). Against selected other currencies, it has risen much more. It has risen 21.5% against the yen and 12.6% against the euro (see Figure 2).

The surging value of the dollar has nothing to do with fundamental economic forces. It is all driven by capital movements which are responding to two things: first, the dislocations in the world economy caused by the Russia-Ukraine war, and secondly, central bank interest rate policies to fight inflation.

The Russia-Ukraine war led directly to the shortages of natural gas in Europe and the skyrocketing global price for oil and natural gas. The spot price in Europe for natural gas has roughly tripled since January, leading to double or triple digit increases in the cost of electricity for European households and businesses. The higher cost of importing gas and oil will lead to deterioration in the balance of trade for European nations, and many other oil importers too, such as Japan. This energy shock is likely to cause a recession in many parts of the world. The weaker balance of payments is putting downward pressure on the currencies of many oil-importing nations.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Federal Reserve is raising interest rates to fight the inflation that began last year and was running at 8.5% as of last month. After three interest rate increases earlier this year, the Fed is likely to hoist rates by another three quarters of a point at its next meeting later this month. Other nations are also raising their interest rates, but in most cases by not as much as the Fed is raising U.S. rates.

The widening interest rate differential makes it more attractive for investors to hold U.S. assets, such as Treasury bonds. Demand for U.S. assets, in other words capital flows into the U.S., raise the foreign exchange price of the U.S. dollar. But on top of that, international investors increasingly believe that any U.S. recession is likely to be less severe than recessions in Europe or elsewhere. This makes U.S. equities more attractive than foreign equities and equities account for roughly half of the capital flows in and out of the U.S.

Figure 1. The trade-weighted US dollar index is up 7.4% so far this year.

Source: FRED

In January of this year, the U.S. dollar was already some 17% overvalued, according to a study we carried out back then using standard Peterson methodology[1] for estimating fundamental equilibrium exchange rates. Against specific currencies, the dollar was far more overvalued. For example, it was 22% overvalued against the Chinese yuan and 40% overvalued against the Japanese yen. This year’s rise in the dollar’s value only makes the problem worse. It is a fundamental principle of economics that an exchange rate should be set at a level that enables a nation’s trade to balance, in other words exports and imports should be roughly equal or trending in that direction. The U.S. has not seen such a balance in more than 45 years, definitive evidence that the U.S. dollar has been overvalued for decades.

The overvalued dollar is a huge problem for U.S. manufacturers and farmers. It is one of the prime causes of escalating U.S. imports, which, at $2 trillion in just six months, are running 23% higher than last year’s imports at the half-year, despite the fact that our economy is roughly flat this year.

Figure 2. The dollar is up 16.3% against the pound sterling, 12.6% against the euro, and 21.5% against the Japanese yen so far this year.

Source: FRED

The scale of the problem is clear if we look at dollar overvaluation as a tax on domestic producers and a subsidy to importers. A global overvaluation of 24.5% (January’s 17% plus this year’s 7.5%) is equivalent to a subsidy worth $980 billion on this year’s imports which are on track to reach $4 trillion. It’s also a handicap on our roughly $3 trillion of exports this year, worth about $735 billion, for a total handicap on U.S. production of $1.72 trillion.

Compare that to total U.S. tariff revenue this year which is likely to be around $110 billion. The benefit to importers from the overvalued dollar is 15 times more valuable than the small handicap of the tariffs.

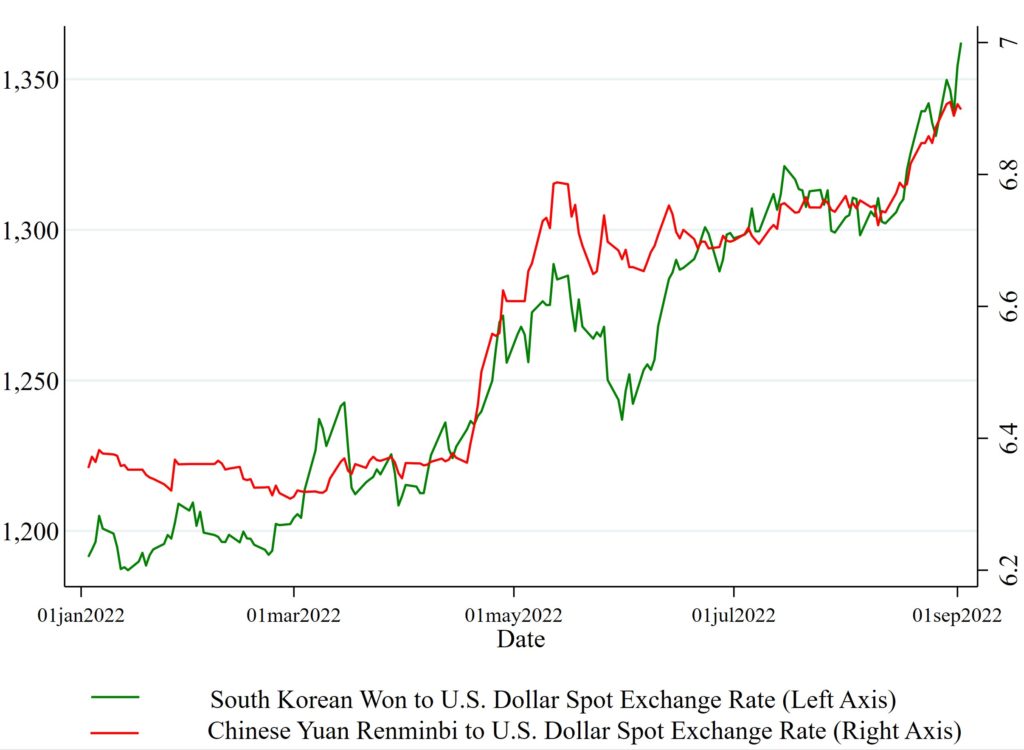

We can make the same analysis about bilateral trade with China. The U.S. has run its largest bilateral goods deficit with China for years, and this year’s China imports are on track to reach a record $586 billion, as we calculated in this recent analysis. With U.S exports to China likely to reach $144 billion, the two-way trade flow is worth some $730 billion. Our overvaluation with respect to the Chinese yuan was 22% at the start of this year. As Figure 3 shows, the Chinese government held the yuan stable around 6.33 to the dollar for the first four months of this year. However in April, either because of weakness in China’s domestic economy or because of the upward trend in the dollar, the People’s Bank of China took a decision to allow the yuan to fall. It has fallen steadily since then, to close to 7 yuan to the dollar, a decline of some 9.5%.

So as of today, the yuan is about 31% undervalued compared to the dollar. That is a benefit to China worth some $226 billion on this year’s bilateral trade. Our Section 301 tariffs on China are running at some $50 billion a year, so the currency benefit is worth more than four times the value of the tariff handicap on China’s imports. None of these calculations include U.S. de minimis imports from China, which we have estimated at an additional $145 billion a year.

To provide a concrete example, China is focused on becoming a leader in the EV (electric vehicle) market. An upmarket Chinese-made EV, the Polestar 2, is now available in the U.S. Polestar lists its retail price at $48,400. At that price it competes directly with the mostly U.S.-made Tesla 3, which has a base price of $47,000. The 9.5% fall in the yuan this year gives Polestar an artificial $4600 advantage in the U.S. market. The cumulative undervaluation of 31% amounts to a $15,000 advantage for the Chinese vehicle. The battle for global leadership in the EV market will be one of the defining features of the world economy over the coming decade.

As another example, fast-growing Chinese teen fashion retailer Shein reached revenue of $16 billion last year. Its website now offers a 15% discount on all online purchases by Americans. The fall in the yuan pays for two thirds of that discount, enabling Shein to continue its aggressive growth, taking business away from U.S. or European retailers of affordable fashion like Target or H&M.

Figure 3. The dollar is up 8.6% against the Chinese yuan and 14.3% against the Korean won so far this year.

Source: FRED

A New Plaza Accord?

As severe as the dollar’s impact is on the U.S. economy, it is actually worse for others. Sri Lanka’s default on its debt earlier this year was due partly to the rising dollar making it harder for the troubled Asian nation to meet its payments on dollar bonds. International economist Brad Setser recently identified several other emerging economies, including Pakistan, Egypt, Ghana, and Kenya suffering from dollar-related “debt distress” and at risk of defaulting.

For some advanced economies, the danger is almost as bad. The United Kingdom has seen the pound sterling fall by 16% since the start of the year, to new lows not seen for almost 40 years. As the new Conservative government struggles with skyrocketing energy costs, a likely recession, and a potential balance of payments crisis, there are growing worries the pound could fall below $1, which would require emergency measures for an economy that has not shown a trade surplus in over 20 years.

Meanwhile, Japan is struggling with severe problems of price inflation and supply chain snafus made worse by the plunging yen. This year, the yen dropped to a shocking 140 to the dollar, its lowest level in 20 years. Only a year ago, the yen was around 110 to the dollar and it was widely thought undervalued at that level. Today its low value is raising the cost of imports in a country that is thoroughly dependent on imports for its food supply. The Japanese government and public are steeling themselves for the start of October, when Japanese supermarkets will be allowed to raise food prices on 6,000 items to make up for the 48% rise in imported food prices over the past year. It will be the largest price shock Japan has experienced in decades.

If we step back, the high and rising dollar is making the world’s existing economic problems worse in many ways. For the U.S., struggling with the loss of good jobs and sinking real wages due to the decline of many high-paying industries, the rising dollar is exacerbating the trillion-dollar trade deficit. For Europe and Japan, sinking currencies are worsening inflation, forcing them to squeeze their economies even harder with fiscal and monetary policy, leading to more severe recessions later this year, next year, and perhaps into 2025. For emerging market nations, the rising dollar threatens their financial stability at a time when the rising cost of basic foodstuffs like wheat is making it harder for them to feed their people.

It is in this context that the Japanese Minister of Finance Shunichi Suzuki raised the idea of a coordinated intervention by major economic powers to drive the dollar down, raise the value of other depressed currencies, and try to bring some broader stability to global exchange rates. “We are concerned that the yen’s depreciation has been one-sided…We will take necessary action if this continues,” he told the press last week. The South Korean minister of finance has also criticized instability in the currency markets.

A coordinated intervention in the foreign exchange markets, led by the U.S. and supported by several major international economic powers, would likely succeed in bringing the dollar down to a more competitive level, provided the governments showed the required confidence, determination and resolve.

At CPA, we support a unilateral U.S. approach that would achieve the same objective in a more enduring fashion, a small fee charged on incoming capital flows known as a Market Access Charge, that would disincentivize foreign investors from buying U.S. dollar assets. This fee would enable the government to steer the dollar down to a more appropriate level and introduce more stability into international currency markets.

Either of these two approaches would work today. If the Biden administration adopted either approach, it would be seen as taking aggressive and creative action to fight off global recession and instability.

Footnote:

[1] The Peterson methodology involves using IMF forecasts of where major global economies will be five years out in terms of gross domestic product and current account balance and then calculating how much each exchange rate would need to change to bring those current account balances at or close to zero.