The de minimis trade provision, a Customs rule that allows for shipments to the U.S. to be brought in duty-free if under $800, is a great way for countries to break the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA). It doesn’t matter if it comes direct from China or through a third party, including Canada and Mexico. De minimis is a gold mine to get all sorts of products from Xinjiang that may have been made with forced labor.

“On average, the U.S. receives around three million de minimis shipments per day, and in 2022 it was even more than that. Is this a gaping loophole that needs to be closed?” asked Rep. Christopher Smith (R-NJ), chairman of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China.

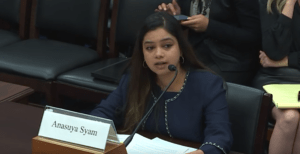

“The de minimis shipping provision is being used to circumvent UFLPA,” Anasuya Syam, Human Rights and Trade Policy Director for the Human Trafficking Legal Center responded on Tuesday in a hearing about the UFLPA and its impact on supply chains. Syam mentioned a letter to Shein’s CEO signed by three Senators, including former presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) in February. The Senators asked for assurances that Shein was not using banned cotton to make clothes for sale on its massively popular website. Shein is a huge beneficiary of de minimis as most of its clothing items sell for under $20, let alone $800. To whit, Syam said that the letter had not yet received a response.

“The de minimis shipping provision is being used to circumvent UFLPA,” Anasuya Syam, Human Rights and Trade Policy Director for the Human Trafficking Legal Center responded on Tuesday in a hearing about the UFLPA and its impact on supply chains. Syam mentioned a letter to Shein’s CEO signed by three Senators, including former presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) in February. The Senators asked for assurances that Shein was not using banned cotton to make clothes for sale on its massively popular website. Shein is a huge beneficiary of de minimis as most of its clothing items sell for under $20, let alone $800. To whit, Syam said that the letter had not yet received a response.

“The U.S. should reduce the de minimis rule so that China cannot benefit from forced labor,” said Elfidar Iltebir, President of the Uyghur American Association. “We know China is taking advantage of this rule, and breaking up shipments to go under the $800 threshold to come in duty free with little oversight.”

Rep. Jennifer Lynn Wexton (D-VA) mentioned de minimis on numerous occasions, including in her opening remarks before the Q&A session. During the session, she asked if Congress should enact laws that require more info on de minimis shipments and their contents.

Laura Murphy, Professor of Human Rights and Contemporary Slavery at the Helena Kennedy Center for International Justice at Sheffield Hallam University in the U.K. said, “de minimis is a way to breach the UFLPA.” The Helena Kennedy Center is known for its reports on the Uyghur situation in Xinjiang. This month, the Center released a 7-page report on forced labor in Xinjiang.

As of September 2020, the XUAR government claims to have placed 2.6 million Uyghurs and others in these state-sponsored programs; in 2021, the government reported as many as 3.2 million people transferred. It appears that the program is growing significantly. Those who are conscripted into the programs are compelled to transfer to work in farms and factories across the Uyghur region, as well as into the interior of China. For those who don’t come directly from the internment camps, the government required that at least one person from every household in Southern Xinjiang accept a state-mandated labor transfer to a factory or farm. In December 2021, government directives required that all people who were able to work must be in some form of work. These transfer programs are tantamount to the forcible transfer of populations, forced labor, human trafficking, and enslavement by international definitions and protocols. – “Forced Labor in the Uyghur Region,” Issue Brief 1, April 2023, Helena Kennedy Center

Chairman Smith said the $800 threshold was high, and wondered how CBP could control all of those packages. To which Syam replied, “I would more closely scrutinize this de minimis provision.”

Chairman Smith seemed quite new to the entire concept of de minimis and Customs’ work in reviewing the mountain of packages it receives. “Who is even looking at all of these packages,” he asked her.

“CBP reviews them. All the courier carriers bring them in. And for getting below the $800 limit, companies will just break packages up into smaller parcels,” Syam said.

“I would hope the CBP is taking an aggressive look at these packages so we are not being duped,” Chairman Smith responded. “We really need to focus on this area big time.” He noted that Sheffield University has identified 55 thousand companies in the Uyghur region, with about 3,300 working in fabrics and apparel.

“I would hope the CBP is taking an aggressive look at these packages so we are not being duped,” Chairman Smith responded. “We really need to focus on this area big time.” He noted that Sheffield University has identified 55 thousand companies in the Uyghur region, with about 3,300 working in fabrics and apparel.

Murphy was the more daring of the four witnesses, calling for all of those companies to be put on the Entity List in gradual steps. “We should presume that all of those companies are tinged with forced labor, especially if we are going to presume under the Uyghur Forced Labor law that forced labor is everywhere in Xinjiang. Yes, it’s a lot of companies to add, but we can start by excluding all the state-owned operations who have been instrumental in transferring Uyghur workers to other states.”

Co-Chair Jeff Merkley (D-OR) wondered if China would just ship suspected goods to Canada and Mexico and have them come in duty-free from there, be it through the de minimis rule, or the USMCA free trade agreement.

Syam said Mexico had a law that will ban imports from Xinjiang in May, so that could help. She did not mention Canada. And Murphy said the EU is doing the same, only these are only bills and not yet laws. The EU bills also are careful not to single out China but ban forced labor goods worldwide.

“I’m concerned that many of these banned products that get caught by Customs here are just getting re-exported to other countries anyway,” Merkley said.

Syam noted that of the roughly $1 billion captured last year under the UFLPA, most of the goods found its way into the U.S. after clearance. Less than 25% were sent back. Some products are still held up and under review.

Chairman Smith brought up the other Chinese e-commerce platform Temu, which made its debut in the U.S. on Superbowl Sunday and is now one of the most downloaded apps in the U.S., selling clothes, shoes, and other goods like cell phone accessories at bargain basement prices one can only find in China. “Should Temu goods be suspect under UFLPA,” he asked.

Kit Conklin, Nonresident Senior Fellow at the GeoTech Center of the Atlantic Council, said he didn’t know. “The company doesn’t matter. Regardless of who it is, or what the shipment price is, we have a law on the books that bans all forced labor goods from China, and that law should apply to Temu.”

An International Trade Today article published on Tuesday featured remarks made by two senior CBP Office of Trade staff suggested that a good 25% of goods shipped in via de minimis are problems.

Even with Amazon and UPS enrolled in two of CBP’s enhanced data pilot programs (namely Type 86 and Section 321), some 25% of the data they were getting on the packages were junk, with an estimated 25% evading inspection even though they are on a CBP hold in a port facility.

The gist of that article suggests the majority of de minimis shipments are a black box. There’s too many of them. The only obvious data about an overseas package coming under the de minimis duty-free exemption will be a physical written mailing label, declaring a value, and offering a couple of words to describe what’s inside. There is simply no way CBP has enough staff to go through one million packages. No one is policing that and there’s no end in sight to the nonstop flow of goods, which includes contraband and even narcotics.

Carlos Martel, director of field operations at the Los Angeles Field Office of Customs, which handles about a third of the national volume of de minimis packages, said in the article that his team ran an operation that flagged “quite a few shipments” – all de minimis — as non-compliant. All the packages together were worth about $4,700. All the packages had been released and had to be seized afterward, requiring about 7,000 man-hours.

CPA’s Vice President of National Security, Robby Smith Saunders, was acknowledged by Chairman Smith at the hearing’s opening. She and CPA Trade Counsel Charles Benoit sent a letter for the record. Here are some excerpts from that letter:

Currently, there is no attempt to enforce forced labor Withhold Release Orders against merchandise entering through Section 321 of the Tariff Act of 1930, known as ‘de minimis shipments’. Even the most basic data, like merchandise country of origin, is typically lacking for de minimis shipments. De minimis imports are done by ‘consignees’, typically mail carriers or express couriers, who cannot speak to the package beyond what is written on the manifest. The manifest description in turn may be as simple as one or two words. CBP is clear when pressed by legislators: there is no policing of de minimis or application of UFLPA to the de minimis channel, which accounts for over two million shipments per day. Failing to repeal de minims signals an unwillingness to tackle forced labor seriously.

Worse yet, via regulation, Treasury unilaterally broke with hundreds of years of customs law, saying that any mail carrier or express courier (‘consignee’) could make entry of merchandise entering via Section 321. This was a profound repudiation of the expectation in customs law that the importer be able to answer questions about the merchandise to a customs officer. This meant individuals and entities making imports had title to their merchandise, and was either present before a customs officer or engaged a customs broker.

Repealing this requirement for de minimis shipments gave every retailer in the world direct access to American homes. We receive millions of these shipments daily and have little information about the majority of them. All a foreign vendor has to do to claim de minimis treatment is assert that the value of the shipment, in their country, is worth less than $800. Foreign vendors are able to hand-write these declarations completely outside our jurisdiction, and 99.9% of them will necessarily be accepted at face value, as our customs authorities have no capacity to inspect thousands of mail-box sized shipments per shipping container. Toys can’t be tested for lead. Apparel can’t be checked for forced labor cotton. All of our product safety rules go out the window if the foreign vendor merely asserts de minimis.

Sure enough, 62.5% of de minimis shipments originate from China and Hong Kong. The second largest shipment origination country is Canada. It is safe to assume that the majority of these shipments are not ‘Made-in-Canada’ merchandise. Instead, they certainly consist of mostly Made-in-China merchandise, sitting in bonded warehouses in Canada along the U.S. border, waiting to be delivered within 48 hours of a customer making a purchase online. This is civilizational suicide, and it must end. – Charles Benoit, in written testimony to the Congressional-Executive Commission on China, April 18, 2023.