Last week, President Biden removed Russia from its Permanent Normal Trade Relations (PNTR) status with the United States on account of its war with Ukraine. It wasn’t hard. It is easy to target an invading force going after a weaker opponent. And the political headwinds were too great for Russia. Businesses left, with most of them able to afford a temporary close like Pepsi and McDonald’s, or a total exit, like Goldman Sachs.

But pulling China from its PNTR status will not be as easy. Despite China being Russia’s most powerful ally in the war, signing lucrative oil and gas deals, and agreeing to be a major importer of wheat that would have likely gone to Europe, secondary sanctions on China are merely an idea.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen even said recently that the idea had little traction. “I don’t think it’s necessary or appropriate,” she said on March 25.

On Thursday, commissioners from the U.S. China Security and Economic Review Commission asked if removing PNTR for China was warranted, not because of Russia, but because of China’s non-market economic status and its oversized impact on U.S. manufacturing.

Nazak Nikakhtar is one of three panelists on April 14, 2022 at a hearing by the U.S. China Economic and Security Review Commission.

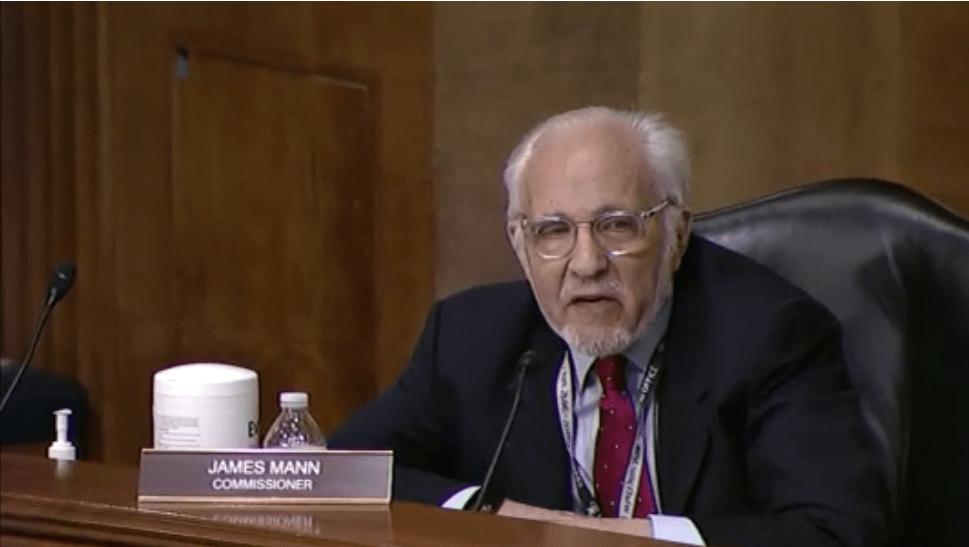

“Should we repeal PNTR? Is that a wise move or not?” asked Commissioner James Mann in panel one of a full day hearing titled Challenging China’s Trade Practices: Promoting Interests of U.S. Workers, Farmers, Producers, and Innovators.

“The PNTR question is very slippery. I think it was a mistake to give this to China in the first place,” said Clyde Prestowitz, Founder and President of the Economic Strategy Institute. “But having done so, to withdraw it, I think, would be very difficult because we are in the WTO, and we are probably not going to withdraw from the WTO.”

Nazak Nikakhtar, Partner at Wiley Rein and a former trade official working in the Trump administration said removing PNTR for China is unlikely.

“I don’t think (removing) PNTR is possible, but I think instead you identify critical materials and raise our tariff rates there. You can use article 21 of GATT to do that. And the reason you want to do that is to make sure that we can invest in the United States and make those industries grow rather than being displaced by Chinese imports. Our priority shouldn’t be about more trade deals….it should be about giving Chinese companies less opportunities to exploit our market.” — Nazak Nikakhtar.

Commissioner Carolyn Bartholomew asked them if any of our trade policies and restrictive measures changed China’s trade practices?

“No. We have not changed their non-market practices,” said Alicia García-Herrero, an economist and a Senior Research Fellow at Bruegel, a European think tank. “But our tariffs have scared China. They have made life very difficult for China, especially for companies on the Entity List. In my opinion, the Entity List has been the most successful,” she said in regard to ways Washington can restrict trade with China.

Nikakhtar called the Entity List like playing whack-a-mole.

“China has millions of companies. We will not block them all and can’t really keep up,” she said. “You need to be serious about cutting off ties and companies will find other markets to sell to.”

For Prestowitz, if PNTR was not an option to raise tariffs across the board for Chinese imports, the second-best option would be a more active Commerce Department. Prestowitz told the Commission that Commerce should return to self-initiating anti-dumping cases against companies. “They have the power to do it. They did it once against Japan semiconductors and should do it again,” he said.