U.S. tech companies like Intel have to seek permission to sell certain computer hardware and software components to a list of Chinese companies maintained by the Commerce Department. The main goal was to slow down advanced technologies going to China’s military, though the restrictions also had a side effect of speeding up China’s nascent advanced technologies product lines there. When Huawei announced it had a new phone called the Mate-60 using a small seven nanometer chip that – until then – was not something China could make, many in Washington felt the U.S. export controls had failed. They called for more.

This week, the Biden administration said it would restrict certain microchips used for artificial intelligence technologies. Nvidia, a U.S. headquartered company, said those restrictions would not just impact its chip sales to AI companies in China, but also to video game producers. A lot of this will fall on deaf ears at the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS), the Commerce Department agency in charge of export controls. For the BIS, and many in the Biden administration, China’s military-civil fusion policy means that chips going to hypersonic missiles and video games are dual-use, and if they are dual-use, they will be restricted.

Restricted doesn’t mean banned. In fact, despite restrictions, many companies are able to get their hardware off to Chinese partners anyway.

“The solution is not hard. We need better export controls. It’s not that they have failed, they are replete with loopholes,” said Nazak Nikakhtar, Former Assistant Secretary for Industry and Analysis at the U.S. Commerce Department and now Chair of the National Security Practice at the Wiley Rein law firm in Washington. She was speaking at a China Tech Threat event to discuss a joint study with CPA called Cash Over Country. The event was held at the Longworth House Office Building on Tuesday in the capital. About 100 people attended.

Nazak said that the government needed import controls as well, and touted the CHIPS Act as a way to provide tax incentives and support for companies to make semiconductors here instead of there.

High Tech Made in China 2025…and Forever

China’s Made in China 2025 document targets self reliance in industries considered critical to their economy. In 2019, China’s Communist Party said that they wanted to make sure the microchips they needed were made locally. The target was for 80 percent of semiconductors to be manufactured in mainland China. This could mean that Intel or Nvidia manufacture chips in China, too. These commodity microchips are in everything from the household refrigerator to the automobile.

In addition to legacy chips, there was a focus on creating and developing advanced chips, the type of chips where the transistors on the chip are so small that even a conventional microscope could not see them, an electron microscope is required to see them fully.

Jeff Ferry was one of the three speakers at the China Tech Threat event, hosted by China Tech Threat founder Roslyn Layton. Ferry is also a former executive at numerous Silicon Valley companies, including chip makers like Infinera. He said China’s desire to circle the wagons around its own manufacturers of semiconductors is yet another piece of evidence that China is not interested in Western-style open market competition between manufacturers. They are about building up their own domestic producers, often at the expense of others. “China has no interest in free trade or globalization. They are interested in building up their own sectors of the economy, including the use of their civilian-military fusion policy, and nothing is more important for that policy today than the production of semiconductors.”

Biden had previously imposed export controls on equipment used to make the machines that make those chips. “These controls on equipment are not working. They are not stopping China from developing and building advanced microchips,” Ferry said.

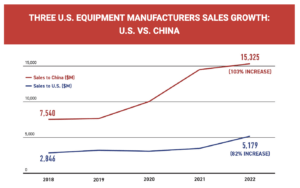

Sales Booming for Global Semiconductor Equipment Makers

Sales revenue for the big industrial equipment makers for the chips industry is up. That includes sales to China, which last year were around $18 billion versus $7 billion in sales to the U.S.

Those numbers alone show how clear it is in Washington that the semiconductor industry was Asia-bound and without restrictions the U.S. would, at best, be designers of chips living off intellectual property (which China can license or steal) and contract with China-based companies to make them. The chip industry would be completely owned by what the U.S. Director of National Intelligence has consistently considered as the No. 1 strategic and economic threat to the United States – the CCP.

The US companies making and selling this equipment are Applied Materials, KLA, and LAM Research.

China is a larger maker of chips than the U.S., but still smaller than Taiwan. It is moving towards dominating the global factory business for chip making, investing billions annually.

“They are more serious and more determined to be the world leader in legacy, mainstream chips as I call them…and in advanced chips,” said Ferry. “Chinese domination of the mainstream chip making market does not just threaten our ability to make chips here, but it threatens the manufacturing industry as we saw with cars during Covid that were not being produced here because we could not get our hands on mainstream chips. China’s market concentration affects the auto industry, the defense industry, the computer industry and will eventually make them all even more dependent on China than they are today.”

The new Huawei smartphone is taking away sales from Apple’s iPhone 15 in China, Ferry said. It’s like that old song from Annie Get Your Gun, Beijing is looking to Washington and singing, “anything you can do, I can do better.”

The BIS has the capability to increase the effectiveness of export controls. But more than that, the U.S. must do all it can to protect and incentivize its mainstream and advanced chip manufacturing base. If the government fails in this regard, there is nothing stopping U.S. chip makers like Nvidia to strictly design the chips here and have it all made in Asia, most likely in mainland China or Taiwan.

Steve Coonen, Former Senior Foreign Affairs Advisor, Defense Technology Security Administration, was also on the panel Tuesday. He gave an insider’s perspective on how export control policy actually works inside the BIS. He said there are two key elements to consider when imposing these export restrictions on U.S. tech companies selling to China. One is who is the ultimate end-user and how they will use the product. For allied countries, the U.S. are comfortable with them using the tech in a dual-use manner – meaning consumer use, or military. But China’s military-civil fusion policy, where retail use chips can be diverted purposely to defense contractors, makes it harder for U.S. companies to know who the end user really is, said Coonan.

“We have a mechanism with other trading partners where we can verify the end user is not diverting their technologies from where they said it was going to go when they bought it over a period of years, but we don’t have that with China,” he said. “There are only two export control officers even assigned to China and we sell more dual use control tech to China than to any other country in the world and we approve over 90 percent of those products” he said about the companies of the BIS Entity List.

China says its end-users can sell the imported product to another company within six months. The U.S. has no mechanism in place to verify where it ends up.

“The economic argument is more persuasive than the national security issue and those who are responsible for the national security aspect of this are not doing their job very effectively,” Coonan said.

How Did We Get Here?

Prior to the Trump administration taking over, the U.S. China relationship was considered untouchable. There were some rumblings about Taiwan and the South China Sea, but trade had no detractors. Things changed in 2018 when Trump imposed tariffs and started restricting access to technologies, arguing that China was growing like no other emerging market due to IP theft, mostly closed markets, and eventually would surpass the U.S. on the tech front.

Worse yet, U.S. companies seemed fine with keeping China as their go-to manufacturer. That ended with Trump, and Biden is continuing these policies and expanding them.

There are a handful in the House and Senate who want a return to the status quo with China.

In the Senate, Mike Crapo (R-ID), the ranking member on the Senate Finance Committee, and in the House, Rep. Patrick McHenry (R-NC10), chairman of the House Financial Services Committee, are both opposed to most capital controls and export restrictions targeting China.

Nazak said that, today, there are Chinese components everywhere in the U.S., from defense equipment to America’s telecom infrastructure. Some of that technology is mainstream chip-based, but not all. For example, China is a leader in 5G technologies, led by Huawei, and is a top five manufacturer of wireless routers.

The latest export control rule looks like “small bites taken out of the apple,” she said, adding that the CHIPS Act might save the industry yet.

There is some low hanging fruit that the government can pick at to improve BIS’ work. “Forget the presumption of denial. You keep that presumption in place and it goes back to a case by case basis review and exports gets approved,” said Coonen. “The policy should be a blanket policy of denial.”

“We are making our industries dependent on China for semiconductors,” Ferry said.

For example, Texas Instruments subcontracts a lot of chips it makes for auto companies to Taiwan Semiconductor, which subcontracts a lot of that work to mainland China.

“To allow China to dominate those industries is like putting millions of jobs in their hands,” Ferry said. “About 90 percent of the LED lights sold in this country are made in China and Taiwan. Every military vehicle has a dashboard with those lights in them. We are on a trendline whereas in five years, max ten, every technology and military product will be dependent on Chinese supply chains.”