Senators representing big agricultural districts said their constituents do not like the so-called Climate Disclosure Rule being tossed around the halls of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

The debate over the rule should be of high interest to CPA’s agriculture members.

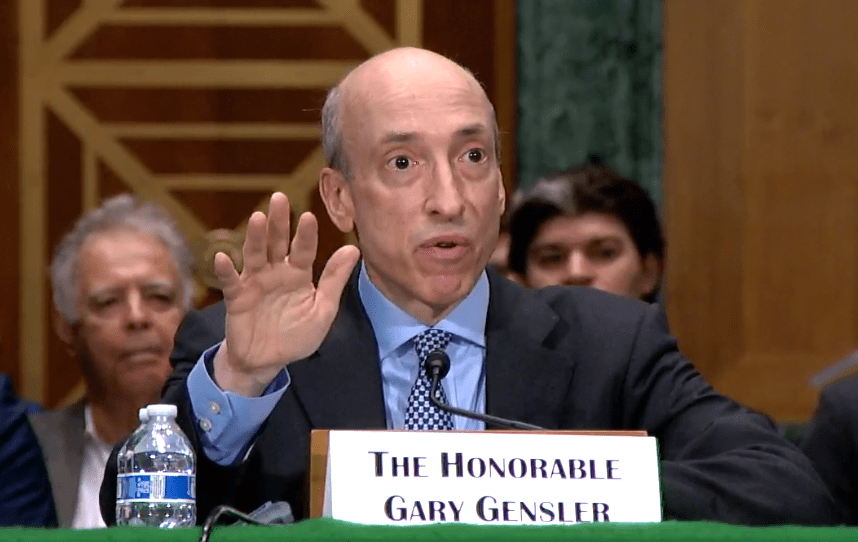

“We have had previous conversations about making sure that the proposed Climate Rule does not lead to burdensome reporting requirements. To add additional workload with all these surveys you are sending farmers again and again and again is a pain in the neck. And I’m being generous when I say pain in the neck,” said Senator Jon Tester (D-MT) during a Senate Banking Committee hearing on Sept. 12 with SEC chairman Gary Gensler. [Testimony]

The SEC’s climate rule seeks to make it so companies that are disclosing their reductions in greenhouse gas emissions (GHG), and other environment-related issues, have exact reporting requirements. To the SEC and those who support this rule, it means an investor can decipher whether Company X’s GHG disclosure can rightfully be compared with Company Y’s. Europe is doing this. Large asset managers there are the main ones pushing for it. The same goes with the U.S., with the vast majority of the more than 12,000 responses the SEC has received on this issue in its public comment period coming from global asset managers who want a reliable way to compare companies on their GHG reporting.

The problem with the rule is something called Scope 3, which would require publicly traded companies that report their climate targets, to also note about greenhouse gas and other environmental pollutants along their supply chain. In theory, this could cause a publicly traded company to turn away from private companies in their supply chain if those companies are not helping them with their climate targets. That affects farmers and ranchers who either sell to publicly traded food processors like Tyson and Archer Daniels Midland, or whose lenders are publicly traded and also report on their climate change-related targets in their financials.

Tester said Scope 3 was a negative for agricultural producers who do business with publicly traded companies, which are the majority of a rancher and farm owners business partners.“We have discussed in this hearing before that it is not the Commission’s intent to have farmers or ranchers in Montana or any other state, or any other ag producers have to report on the goods that they sell to publicly traded companies. And I want to make sure that that still stands true. Is that right?” Tester asked Gensler.

“That does stand,” Gensler replied.

Gensler said that of the top 1,000 companies by market cap, about 80 percent of them make Climate Risk Disclosures in their financials.

“We’ve heard from many farmers and ranchers, from a lot of small and medium-sized enterprises who’ve said look, we don’t want to fill out the surveys as you said. And so I’ve asked staff to really take a close look at those comments to make sure that we’re only regulating the public companies, and not somehow indirectly regulating private companies,” Gensler said.

Sen. Tester: No to the Climate Disclosure Rule’s scope 3 provision.

Farm and ranch owners have been getting questionnaires inquiring about the use of pesticides, fertilizers, power usage, and herd size for the last two years, with increased frequency.

Tester fired back and told Gensler that it was going to take more than the Chairman’s words that this will not impact agriculture. “The bleed down of regulation is something that happens all the time. And I just want to make sure that it is crystal clear that people in agriculture are not going to be faced with these surveys,” Tester said.

Gensler said he has received thousands of comments from farmers and “asked staff to come up with solutions.” He told Tester that Scope 3 was not fully thought out yet. But while he said no private entity needed to report on their emissions, he said public companies could report it themselves in an estimated guess “if they found it material.”

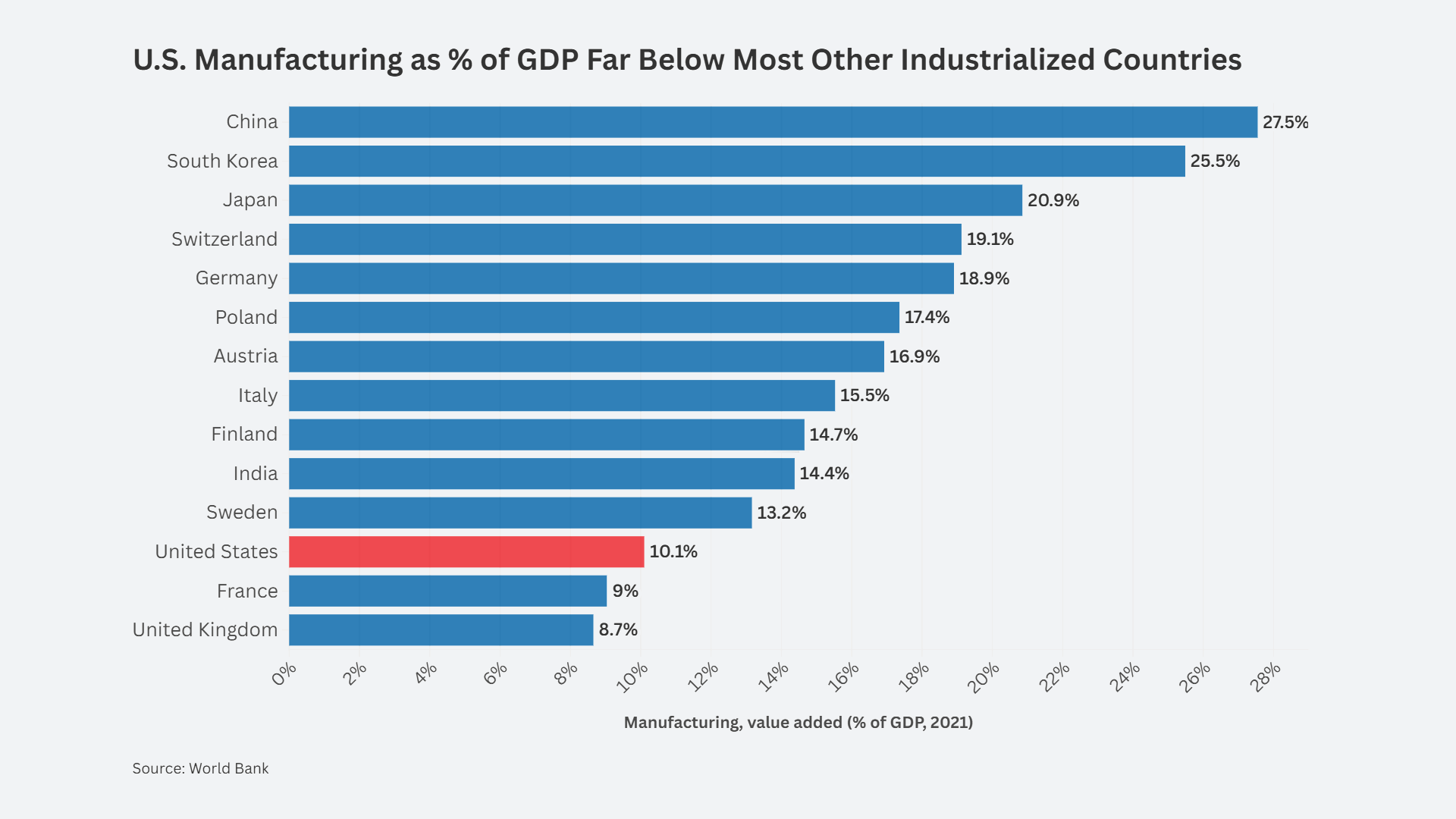

This is the crux of the problem, however, because if companies did find it material that their rancher client is using too much nitrogen in the soil, or a client’s harvest combines are not being battery operated when the opportunity to buy an EV harvester is available, they could turn away from providing financing, purchase less commodities, or add penalties for doing business with them in order to force changes to help the publicly traded company meet its climate targets. Nothing Gensler said in addressing this issue with farm state Senators last week put an end to that possibility. As it is, the U.S. is increasingly becoming an importer of beef and livestock as farmers leave this heavily regulated industry, likely to be made more complicated by the Climate Disclosure Rule.

“The breakneck pace at which you are pumping out regulation should not be applauded,” said Senate Finance Committee Ranking Member Tim Scott (R-SC). [Opening Remarks] “The regulations the SEC has proposed under your leadership are unjustified and are sowing discord and confusion for industry and market participants alike.”

Sen. Tina Smith (D-MN) noted that the U.S. was behind Europe on this issue. “The EU and the UK and the (London-based) International Sustainability Standards Board have all recently taken steps to implement robust climate disclosure standards. This will be reverberating across the globe economically,” Sen. Smith said, adding that an estimated 3,000 U.S. companies will be subject to these EU standards just for doing business in Europe. “Why do you think this is important and what level of urgency do you feel to complete this rulemaking process?” she said, seemingly in favor of the rule. The American Farm Bureau (FB) Federation is against this rule. The FB’s local Minnesota Farm Bureau Federation’s political action committee endorsed Smith for Senate in 2020.

Gensler gave no timeline on when the Climate Disclosure Rule would go into effect and if Scope 3 would be killed, or have a clause to protect farmers and ranchers from publicly traded company mandates on climate initiatives.

“I don’t want to predict on this one,” Gensler said. “It is a very heavy comment file. Really important issues have been raised around the discussion of these disclosures.”

Sen. Steve Daines (R-MT) said the rule would lead to “wildly inaccurate disclosures that will be of little practical use to investors anyway.” He doubted the SEC could police it, though the private sector would do that itself. “I have serious concerns that you even have the legal authority to enact such a rule,” he said.

Daines called the Climate Disclosure Rule part of a climate change-driven policy agenda and clearly wanted no part of it.

Gensler assured him the SEC has “no climate agenda whatsoever. We’re not going to be a climate regulator, sir, but over 80 percent of the top 1,000 companies in 2021 have been making climate risk disclosures and 50 – I think 5 percent are making greenhouse gas disclosures, so the rule is just trying to build some comparability of that which is already happening.”

The SEC works with California and Massachusetts based NGO Ceres, a collaborative of asset managers pushing for similar reporting requirements for environmental pollutants.

Private Equity Markets Courting China

Private equity and venture capital have become a topic for discussion on Capitol Hill lately. For Washington’s China policy, the notion that U.S. capital markets are funding “our greatest adversary” – as nearly everyone in Congress will attest – took an interesting twist on Sept. 12. Both houses of Congress are toying with the idea of restricting private capital from investing in China. But during last Tuesday’s Senate Banking Committee hearing, two Senators brought up Chinese government funds investing in U.S. private equity products.

Sen. Chris Van Hollen (D-MD) said there have been a number of questions surrounding the need for greater transparency in private equity, with the size of private equity sitting at a whopping $20 trillion dollars today.

“I want to ask you about something that has not come up, which is the role of sovereign wealth funds investing in private equity here. Because the Congress has tightened the inbound investing rules, we are seeing less direct foreign investment by China companies but we are seeing a big increase of investment from China sovereign wealth funds or state backed investors,” Van Hollen told Gensler. He named China’s State Administration of Foreign Assets (aka SAFE), and the China Investment Corporation buying into U.S. private equity funds. “On one hand, private equity fund managers here argue that these (China investors) are not voting members, that this is a passive investment for them with no direct control over the decisions or operations of these funds. But on the other hand, as the size of these investments grows, a number of people have raised concerns,” he said, citing a Financial Times article dated May 30th, 2020 titled, ‘Has China become too cozy with private equity?’

Gensler had nothing really to say on that. “We as an agency are neutral about which investors from which countries the investment advisor is advising. Our jurisdiction doesn’t really go there as long as those advisors are complying with anti-money laundering laws and the like,” Gensler said.

“Are you concerned about CCP-linked companies using private equity funds to invest here?” asked Sen. Jack Reed (D-RI). “If that concerns you, what are you doing about it?”

“As a general matter, I think we all probably share the concern about bad actors in our markets, whether they be state actors or non-state actors that use our capital markets for nefarious means,” Gensler said and left it at that.