Key Points

- Global current account imbalances (consisting mostly of trade) increased in 2021, the most recent data available. As a percentage of world GDP, total imbalances reached 3.6%, equivalent to $3.3 trillion. Imbalances have worsened during the pandemic and the post-pandemic period, driven by rising goods trade flows, mainly from Asia to North America.

- Persistent imbalances show the global trading system is not working. Several nations run large, persistent surpluses, which are beggar-thy-neighbor policies designed to build up their productive bases. The persistent deficit countries lose out on productive power and good jobs.

- China, Germany and Japan were the three top surplus countries which overproduce, underconsume and rely upon foreign consumers for growth.

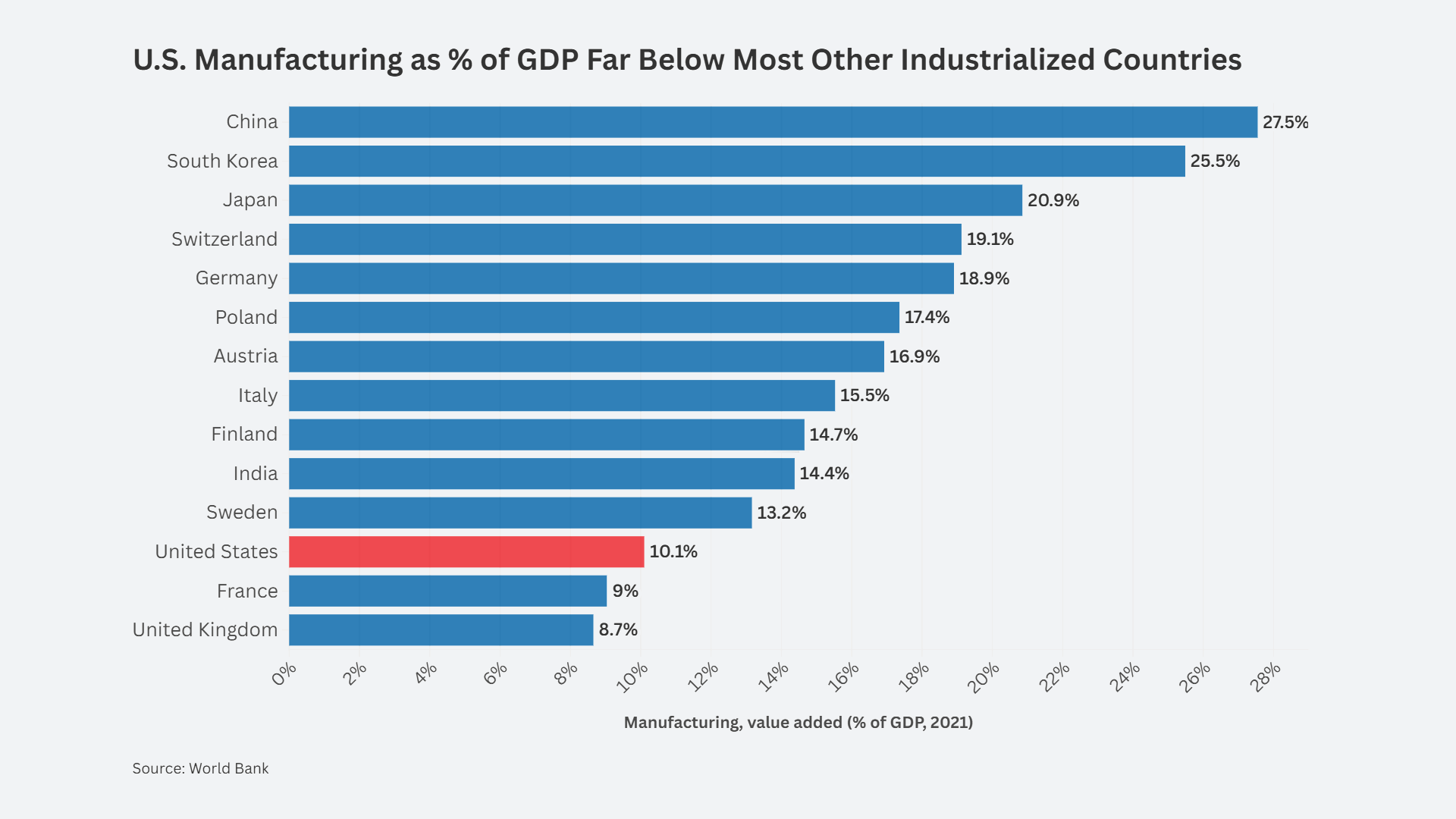

- The leading deficit country is the U.S., followed by the UK as a distant second, absorbing the excess production of the surplus countries. Persistent deficits hold back the growth of the U.S. economy, cause deindustrialization and supply chain dependence, as well as the loss of middle-class jobs.

Global Imbalances Expanded in 2021

The most recent External Sector Report by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) found that total global current account imbalances increased to 3.6 percent of world GDP in 2021, up from 3.1 percent in 2020. That’s equivalent to $3.3 trillion of imbalances in a world economy worth just over $100 trillion a year. As China’s trade surplus and the U.S. trade deficit expanded in 2022, it is likely that global imbalances will be even larger when the official data is released later this year.

The IMF measures balance in the global economy by nation’s current account balances. The current account summarizes the net of all transactions of goods, services, investments, and financial transfers by non-residents. A net outflow means a country has a currency account surplus. China, Germany, and Japan are the largest surplus countries. The U.S. has the largest current account deficit of -$846 billion in 2021, or 3.6% of GDP.

Current account imbalances are important because persistent surpluses and persistent deficits indicate that some nations are gaining industrial strength at the expense of others. The surplus nations build their economies while deficit nations lose out. Over the last two decades, China and Germany have consistently run large surpluses, obliging other nations to run deficits and absorb their overproduction. The two leading deficit nations that overconsume and underproduce are the U.S. and the U.K.

One of the reasons imbalances grew in 2021 was due to the pandemic and its aftereffects. The pandemic shutdowns in 2020 repressed spending on services. Consumers responded by spending more on goods and a disproportionate share of those goods came from the surplus nations. But the supply chain disruptions at ports and factories in 2021 meant that exporters could not ship all the goods that importers wanted to buy. As supply chains returned to normal in 2022, goods shipments accelerated further to catch up with demand.

Imbalances and Foreign Debt

The IMF tracks global imbalances because imbalances can also lead to dangerous accumulations of foreign debt which create instability and the risk of financial crises. In the 1980s, several Latin American nations suffered a debt crisis when foreign lending was withdrawn. A decade later, several Asian nations suffered a similar debt crisis when Thailand was forced to devalue its currency, the baht, in June 1997. The crisis rocked even financially strong nations like South Korea.

After the crisis, the IMF retreated from its longstanding position that all international capital flows are good. In 2011, the IMF published what it calls the “Institutional View” arguing that at times capital controls can be a beneficial means of preventing the accumulation of foreign debt or dangerous instability.

As shown in Figure 1, while China, Germany, and Japan have run persistent current account surpluses by exporting more goods than they import, the U.S. and the U.K. have absorbed these excess goods and run current account deficits.

Figure 1: Global Current Accounts as Percentage of World GDP (1990-2021)

The IMF report does not consider the long-run drivers of today’s global imbalance. Countries like Germany and China run account surpluses by investing in manufacturing capacity to grow their economy. They allow their currencies to become undervalued to support their large surpluses. In the case of China, the government controls the value of its currency directly. In the case of Germany, membership of the 20-nation Eurozone, all sharing the euro as a single currency, gives Germany a currency that is undervalued for its national economy. These are the underlying fundamentals that distort global trading systems. At some point, global imbalances become excessive. The imbalances distort the U.S. economy by resulting in lower growth, the deterioration of manufacturing capacity, and lower quality of employment for Americans.