The FDA’s generic drug reauthorization deal for next year might be held hostage by Senators who want to find the underlying cause of the ongoing infant formula shortage. The House and Senate health care committees are still debating the user-fee reauthorization and funding for the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) generic drug programs expire in September. But passing those items may now be put on hold.

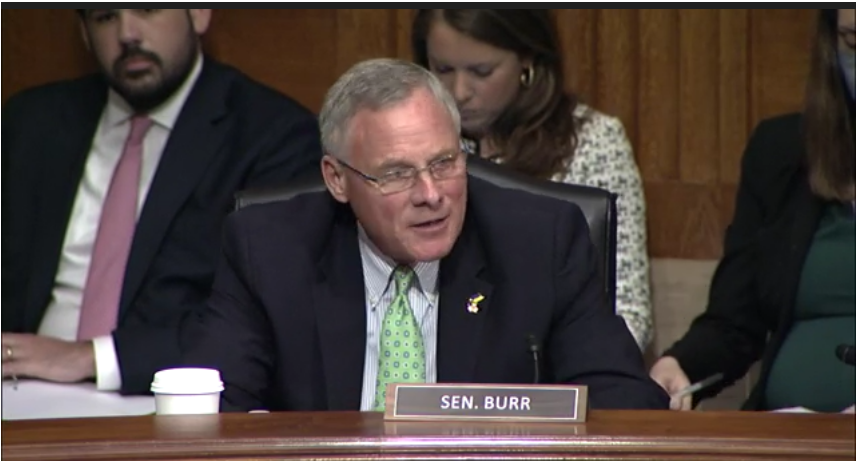

“We are negotiating the next round of the FDA’s user fee agreement and we are really close and once again FDA asking for more money, more authority, less accountability,” a heated Senator Richard Burr (R-NC) told new FDA Commissioner Robert Califf during a Senate committee hearing on Thursday, May 26. “I’m going to have to think about this and wonder whether now the time is to move forward on user fee negotiations. I think figuring out this issue (baby formula) is more important than something that doesn’t expire until the end of the year,” he said. “There are just too many unanswered questions.”

Burr is the ranking member of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions. He was addressing Califf, who had almost no allies in the room, during a hearing titled “Infant Formula Crisis: Addressing the Shortage and Getting Formula on Shelves.”

Chairwoman Pat Murray (D-WA) was just as adamant. She did not backpedal at all on the opposition party’s threat to withhold progress on the user-fee reauthorization bill in light of the latest supply chain crisis. “We want to see a plan on this first, so it doesn’t happen again,” she warned Califf.

Chairwoman Pat Murray (D-WA) was just as adamant. She did not backpedal at all on the opposition party’s threat to withhold progress on the user-fee reauthorization bill in light of the latest supply chain crisis. “We want to see a plan on this first, so it doesn’t happen again,” she warned Califf.

Califf has been at his post for less than six months before all hell broke loose. He was in the hot seat again on Wednesday during the House Energy and Commerce Committee hearing on the same topic, held on May 25.

You can read the FDA’s testimony to the House here.

Califf spent much of the last two days answering the same questions to House and Senate members. They wanted to know about timelines, “mail room screw-ups” on delivery of Abbott Laboratories whistleblower complaints regarding their infant formula facility in Sturgis, MI, the source of the current problem, and they consistently blamed the FDA for dropping the ball.

FDA Commissioner Califf was in the hot seat in the House and Senate in back-to-back hearings. He had very little sympathy from members of both committees this week.

Califf repeated himself that FDA employees were working nights and weekends on the issue, and that the Abbott Labs facilities was in “egregious” disregard for FDA standards of public health at its Sturgis plant. Califf also said that while the FDA could have handled things better, it was clearly a canned statement – as anything that leads to failure could have been handled better. Califf made clear that all steps were followed, and that the slowdown was caused by verifying the Abbott Lab whistleblower’s complaints, and then inspecting the facility.

Shockingly, the FDA’s solution to the problem was always more imports rather than increasing production at home, or getting government contracts, through the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children, aka WIC, to diversify its supply source. WIC is a huge buyer of infant formula and – based on what was heard at the Senate hearing, a majority buyer of infant formula in the market.

At one point, Senator Rand Paul (R-KY) blamed a 17% tariff on infant formula for “economic bottlenecks” to supply chains.

“To those who argue why onshoring is the solution to all our supply chains, this is a classic example of why that’s not the case,” Califf said. “This was almost all onshore products. And the industry couldn’t produce what people needed.”

Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT) fell short of asking what could be done to reshore the industry for the longer term. The solution was always brought down to increased imports. Nestle, not currently a big player in the U.S. market, is now part of the Operation Fly Formula, the Biden administration’s Defense Production Act plan to get infant formula to market as soon as possible by allowing for the fast approval of mostly European imports.

Sanders asked about consolidation of the market, with only three major players involved, and wondered, “What can we do to broaden the number of companies that produce baby formula?”

Califf said he was “concerned about consolidation,” calling it a risk.

Then Sanders asked, “What is the FDA doing to get more companies involved?” He did not say the keyword here, which is “domestic.”

From both the House and Senate hearings it was clear that domestic supply chains were rattled by the Abbott Labs plant closure in Sturgis, Michigan. And that no one else in the market here could have picked up the slack in time. Abbott Labs is indicative of problematic monopolistic markets, and over-reliance on sole source, centralized suppliers for essential products.

Califf told Sanders that the FDA “reduced some paperwork so more foreign manufacturers can import. Nestle had no presence. They will help out quite a bit.”

Sen. John Hickenlooper (D-CO) said the FDA was behind in dealing with supply chain crises, whether in food or drugs, which is clearly the FDA’s top concern, both chambers of Congress agreed.

“We continue to react to supply chain interruptions rather than proactively plan ahead,” Hickenlooper said. “Does the FDA have adequate access to critical supply chain information? Not only for the formula shortage but also to limit the risk to other lifesaving and life-sustaining products?” he asked, likely referring to medication.

“The short answer is no,” Califf said. “I’m a huge advocate for free enterprise and allowing individual companies making independent decisions that are in their interests. It’s worked great for America. But what’s happened is each company has its own supply chain, its own optimization, and if company X gets in trouble, will we have supply for that community? We don’t know. On the drug side, we just got the authority to require the drug companies to notify us when there is a shortage. We had over 300 (shortages) last year that we had to help with. If you talk to hospitals and health systems around the country, they are dealing with shortages every day,” he said. “We don’t have that same authority for food,” he said, adding that government intervention is not always the answer. “There is no reason for the government to intervene…unless there is a public health need.”

In 2020, the FDA produced a list of dozens of generic drugs that were in short supply in the U.S.

In February of this year, an Abbott Labs whistleblower warned that their infant formula plant was shoddy. FDA ruled it was and shut it down, leading to the ongoing shortage.

Weak supply chains for essential goods are a crisis Washington has had in the spotlight since the pandemic began in 2020.

Califf said the Abbott facility is not ready to open. “They had to replace the roofs, replace the floors, but the work is not done. You just can’t open a plant with bacteria growing all over the place. Which is what the inspection showed,” he said.

Committee Chairman Frank Pallone, worried about more supply chain issues the FDA can’t handle.

The House sounded similar alarms. Califf had few friends in the room. Both committee hearings were contentious and white-hot. The FDA was deemed a failure.

House Energy and Commerce Committee Chairman Rep. Frank Pallone (D-NJ-3) said he was concerned about the lack of preparedness once again for future supply chain crunches.

“We have to have a mechanism where the manufacturers tell us if they are experiencing shortages for whatever reason,” Pallone said. “Maybe we need to have some kind of legislation that would require manufacturers to alert the FDA so we can help shift production or empower the FDA to act more quickly. The process is bogged down.”

“We requested authorities to deal with the threat of formula shortages and we were unsuccessful at that,” Califf responded about the shortages and how to deal with them at the FDA level. “Right now, we have no ability to (deal with shortages) and there is no requirement that manufacturers alert us if there is a shortage. There is no national system that makes sure supplies need to go where they need to go. We are having shortages of generic drugs, every day in hospitals. We have to do something about our supply chain,” he said.

Less than 24 hours later, he said reshoring was not really the answer.

Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-WA-5), the ranking member on the House committee that spoke with Califf as well as executives from Abbott Labs, asked about FDA intel on U.S. supply chains for essential goods. “Don’t you have data you can use to monitor the supply chain?” she asked.

“We requested help on this. We didn’t get it,” he said about the tech at the FDA’s disposal. Califf used to work for Google. Based on his testimony, the FDA is underfunded and understaffed and has old tech. “We are working around the clock on this issue,” he said repeatedly to both Committees. “On the tech side, what we have is outdated.”