We Need to be Better at Industrial Policy

By Amanda Mayoral, CPA Economist

Industrial policy is critical to competing in a global economy and maintaining our national security. In the world of U.S. economic policymaking, we need to stop wasting time debating whether to “do” industrial policy and rather debate how to improve it. Industrial policy has been a key part of American policy at every level of government and will continue to be so. The U.S. has many industrial policy tools in our arsenal. In recent years however, our approach to international trade and U.S. industry has largely been to take a blind eye to the advantages given to foreign competitors, to the detriment of our firms and workers. This article outlines several cases of successful U.S. industrial policy. Being better at industrial policy requires a look at what went right as well as what went wrong to learn and improve our industrial policies.

An industrial policy is any government policy targeted at an industry. The goals of industrial policy vary with the number of industrial policies, but generally they can include increasing production, employment, market share, productivity, and overall growth. Methods of industrial policy include R&D investments, subsidies, preferential/easy credit, tax breaks, quotas, tariffs, and many forms of non-tariff barriers.

Aims of Industrial Policies

- Countering other nations’ unfair trading practices

- The government uses a variety of industrial policies to defend U.S. companies from unfair trading practices, particularly subsidized or otherwise more expensive exports to the U.S.

- Protect national security

- While some policies are targeted to increase industrial productivity, a core manufacturing base is necessary for national security.

- Support new industries and raise productivity

- The government can help develop and increase the productive capacity of new industries by providing protection from foreign competitors and funds to advance new technologies.

- Provide for externalities

- R&D efforts in one firm or even industry provide positive technological externalities for other domestic firms.

- Overcome coordination failure

- Industrial policy helps industrialization by overcoming coordination failure. Industrialization requires growth and investment in a range of firms. Without coordination, development of certain industries is less profitable.

A False Debate

Debate over whether the U.S. should engage in industrial policy is a false choice. Industrial policy is not going away. The U.S. has always done it, and our inability to accept this has kept us from being better at it. Industrial policies have been the bread and butter of economic policies in the United States, at all levels of government since our inception. Like every country, we have intervened in the economy at every level and stage of our development. From tax breaks, farm subsidies, vaccines (operation warp speed), or minimum wage laws, we are interventionists and rightly so. It would be reckless to leave our livelihoods completely to the whims of free markets and market failures. Economic policies targeting specific industries are interventionist, and are de facto industrial policies.

Industrial policies must be thoughtful and tailored to the market they are aimed at. Evidence of failed policies does not mean that industrial policy as a whole does not work. It simply means that policy did not work for that market. On the contrary, there are plenty of examples when industrial policy does work. Our job is figure out how to do it better.

A key consideration for policy makers is to properly evaluate which are the “right” industries to promote. This is because if the industrial policy fails to advance an industry, it still cost taxpayer money and can raise domestic prices. Industrial policy should therefore be made with an understanding of the underlying issue in an industry.

The next few sections discuss federal level industrial policies, but U.S. industrial policy truly spans across all levels of government. At the city or county level, local port and development authorities help attract businesses that will increase wages and employment. At the state level, states will often use tax, subsidy, or bidding methods to compete for placement of major developments such as for automobile or semiconductor manufacturing plants. They also provide funds for training schools and grant colleges to help support the local worker needs.

Examples of U.S. Industrial Policy

Biotech Industry

The biotech industry has grown over time with the help of U.S. government National Science Foundation (NSF) grants. NSF grants helped fund the work by Herbert Boyer and Stanley Cohen, the inventors of DNA cloning and central to the technology in the biotech industry (Block & Keller, 2011). This support began in the 1970’s and this type of research received over 100 million dollars by 1987. The injection of NSF money stimulated research between academics and firms in both the biotech and pharmaceutical industries.

The biotech industry also benefited from legislation passed in the 1980’s to encourage the collaboration between academics and firms. Legislation such as the Bayh Dole Act strengthened the legal commercial rights to publicly funded research. The Orphan Drug Act provided patent protection, tax credits, and a quicker method for FDA approval for innovators working on rare diseases. A well-known example of this type of industrial policy is the success of the biotech firm Genzyme, which was originally a consortium of academics funded by the NIH to study Gaucher’s disease. Researchers in the consortium discovered a therapy for Gaucher’s disease in 1983 and were subsequently fast-tracked through the FDA’s approval process by 1985. Ultimately, this team of researchers turned the treatment into a business and eventually became one of the largest biotech firms in the world.

Tennessee Valley Authority

In response to the Great Depression President Franklin Roosevelt passed a series of reforms known as the New Deal. One piece of legislation created the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). Following the collapse of markets during the Great Depression and with widespread poverty in Appalachia, the purpose of the TVA was to modernize the region by investing in critical infrastructure services such as dams, roads, flood control systems, and electricity generation. TVA spans many states, including Georgia, North Carolina, Alabama, Mississippi, Virginia and Tennessee.

The TVA provided annual investments to the region over an extended period. Total government spending for the program was roughly 20 billion dollars, most of which occurred between 1940-1958. By 1960, federal spending declined as the TVA power system had become a self-sustaining entity.

The TVA helped industrialize the Tennessee river region. Even after the power system became self-sufficient and the government subsidies ended, the effects of the TVA on the manufacturing industry persisted. Research by Kline and Moretti estimated that the TVA raised overall U.S. manufacturing productivity by 0.3 percent between 1940-1960 (Kline, Moretti, 2013).

Semiconductors & Batteries

Due to strong competition from Japan in the 1980’s, the U.S. lost substantial semiconductor market share (SEMATCH 1992a). In response, in 1987 fourteen American firms formed the consortium of semiconductor manufacturing technology (SEMATECH). The goal of SEMATECH was to increase competitiveness of U.S. firms by both increasing the volume of semiconductor chips produced and the functionality of the chips. SEMATECH pooled the resources of several companies to stimulate research and innovation in the semiconductor industry (Browning, Beyer, Shetler, 1995).

SEMATECH included industry leaders such as AT&T, Hewlett-Packard, Intel, Motorola, and Texas Instruments. Together, the consortium represented most of the U.S. semiconductor market. Each SEMATECH member provided financial and staffing labor resources to the initiative. The total amount contributed to SEMATECH was 100 million dollars annually, an amount matched by the U.S. government to bring the total investment to 200 million dollars annually. The US Department of Defense provided further financial support to SEMATECH. By the 1990’s, SEMATECH was considered a success as the U.S. reduced its manufacturing costs, increased chip production and productivity, and regained its market share.

In 2008, the success of SEMATCH motivated another consortium to form only this time in the U.S. battery industry. Again facing stiff competition from Japan, several battery manufacturers started The National Alliance for Advanced Transportation Battery Cell Manufacture (NAATBatt). NAATBatt is comprised of over 100 corporate members, extending beyond battery manufacturers to include other companies in the battery supply chain (Greenberger, 2019). More recently, NAATBatt has helped U.S. battery manufacturers compete with China’s major investment in the lithium-ion battery industry.

The Advanced Technology Program

The Advanced Technology Program (ATP) was created in the early nineties between both the Bush and Clinton administrations to stimulate research in new American technologies. The benefit of the ATP is to help firms innovate where the market would otherwise not be willing to invest in risky or new technologies. To support these awards, the ATP was given between 100-200 million dollars annually (Wessner, 2001).

Research on the effectiveness of the ATP shows that the awardees tend to be more successful than non-recipients. Further, following the research award, recipients were more likely grow and receive additional R&D they would otherwise not have received. Despite its benefits, the ATP was suspended in 2007 due to political pressures (Feldman, Kelley, 2003).

Chrysler Bailout

In the 1970s, the US faced increasing international competition, particularly from Japan. Inflation, competition for more fuel-efficient automobiles, and rising oil prices led U.S. automobile makers like Chrysler to experience falling sales and market share. Facing bankruptcy, the U.S. government “bailed out” Chrysler by providing a 1.5 billion loan guarantee in 1980 (Hufbauer, Jung, 2021).

Following a series of cost saving measures and new investments, Chrysler rebounded and released more competitive fuel-efficient cars. These new developments for Chrysler led to record profits of 2.4 billion dollars and higher market share by 1984. As part of repayment, Chrysler provided warrants for the government to buy Chrysler stock (Bickley, 2008). The program was so successful that the government made money on sale of Chrysler stock. Given that the Chrysler workforce was then about 360,000 employees, cost per job was roughly 4,200 dollars, a small investment for a large return.

Military & National Security

The U.S. government has invested billions of dollars in advanced technologies to support U.S. national security and military interests. A well-known example of this type of industrial policy is the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). DARPA was created in 1958 under the U.S. Department of Defense by President Eisenhower as an R&D agency to stimulate U.S. military technological ability. DARPA has played a central role in American technological achievements, such as during WWII, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War. To stimulate research, DARPA provides competitive grants to fund high-risk research.

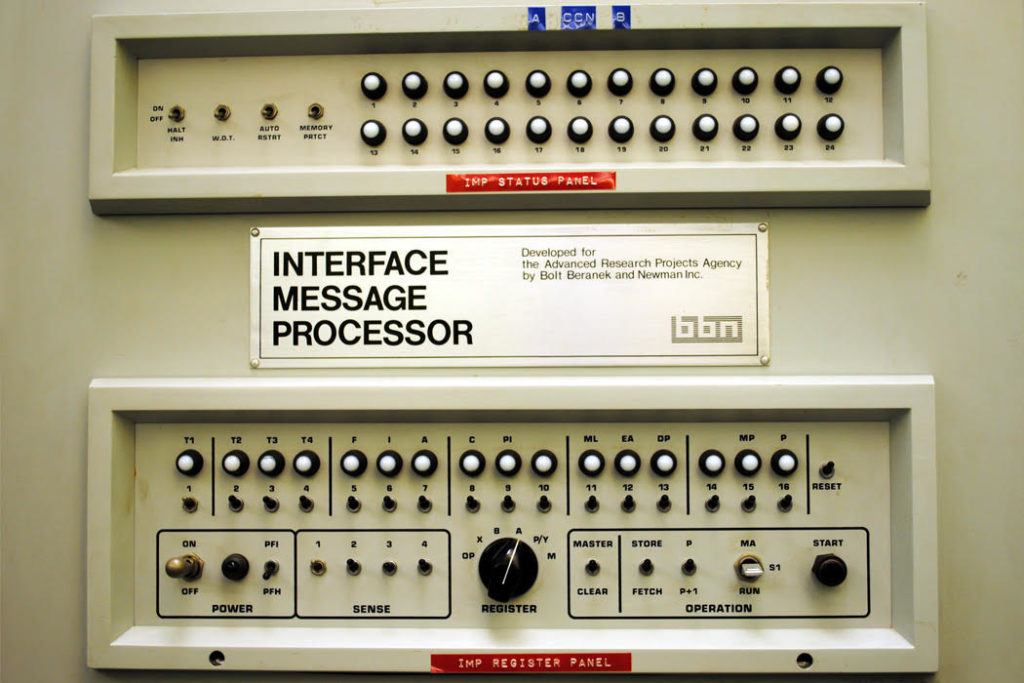

Many technologies supported by DARPA led to positive industrial spillovers and profitable companies. Examples include microelectromechanical systems, prosthetics, and autonomous vehicles. DARPA’s most famous success was its 1968 funding of the ARPANET, a network for university computers to exchange messages. As part of this project, DARPA awarded a contract to Boston area tech firm BBN to build the first router to send the messages to the correct location. These innovations gave birth to the Internet, today a trillion-dollar industry employing millions of people around the world.

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) was created by the federal government in 1958 to advance the space exploration and U.S. industry capabilities in aeronautics. As a result of this agency, the U.S. made major technological achievements and continues to do so today. In addition to meeting its own mandates, NASA helps new and particularly small firms innovate through its programs such as Facilitated Access to the Space Environment for Technology Development and Training (FAST). These programs provide firms with the ability to test and improve their technologies using NASA’s facilities.

In addition to advanced technologies, a core manufacturing base is necessary for national security. This need was clear during the Korean War when President Truman signed into law the Defense Production Act (DPA). A key part of this legislation is requiring manufacturers to prioritize government orders of essential goods during war or crisis times. However, ability to call on manufactures to meet domestic production needs and thereby our national security needs, is increasingly difficult.

Recently, Presidents Trump and Biden have each invoked the DPA to combat COVID-19 in the U.S. To support the DPA, the government spent over 11 billion dollars to stimulate production of medical supplies and equipment and stabilize to the medical supply chain (GAO, 2021). Despite these efforts, the U.S. has fallen short on mobilizing production, largely due to the relatively small manufacturing base available in many health-related industries. Recognizing the US overreliance on foreign manufacturing, Senators Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Tina Smith (D-MN) have proposed legislation to help rebuild the U.S. pharmaceutical supply chain. In the spirit of President Biden’s American Rescue Plan, the Pharmaceutical Supply Chain Defense and Enhancement Act provides 5 billion dollars in investments over five years, particularly for the most critical drug shortages.

Conclusion

Industrial policy is a major component of U.S. economic and national security policy making. From countering anti-competitive foreign practices, supporting and protecting new industries, to assisting in national security, this article demonstrates several examples where industrial policy was a critical tool to promote U.S. interests. While the U.S. has many tools to combat unfair trading practices, we have not kept up with the magnitude of foreign market intervention and our firms and workers have paid the price. Overall, we need to be better at industrial policy, doing so requires a fair and critical look at what has worked, what has not, and how to improve it.

References

James M. Bickley, “Chrysler Corporation Loan Guarantee Act of 1979: Background, Provisions, and Cost,” Congressional Research Service, December 8, 2008.

Fred Block, Matthew R. Keller, In Book: State of Innovation: The U.S. Government’s Role in Technology Development (pp.57-76) Chapter: Political Structures and the Making of U.S. Biotechnology Publisher: Paradigm Publishers, January 2011.

Patrick Kline and Enrico Moretti. “Local Economic Development, Agglomeration Economies, and the Big Push: 100 Years of Evidence from the Tennessee Valley Authority”. NBER Working Paper No.19283, August 2013.

Larry D. Browning, Janice M. Beyer, Judy C. Shetler, “Cooperation in a Competitive Industry: SEMATECH and the Semiconductor Industry”, The Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 38, No. 1 (Feb., 1995), pp. 113-151

James Greenberger, “Testimony Before the U.S. China Economic and Security Review Commission”, U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, June 7, 2019

Charles W. Wessner, The Advanced Technology Program: It Works, “Issues in Science and Technology”, Vol. XVIII, No. 1, Fall 2001

Maryann P. Feldman and Maryellen R. Kelley. “Leveraging Research and Development: Assessing the Impact of the U.S. Advanced Technology Program”, Small Business Economics20: 153–165, 2003.

Gary Clyde Hufbauer, and Euijin Jung, Scoring 50 years of US industrial policy, 1970–2020, Peterson Institute for International Economics, Briefing 21-5, November 2021

U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), “COVID-19: Agencies Are Taking Steps to Improve Future Use of Defense Production Act Authorities”, December 16, 2021