Editor’s note: CPA’s work on the Baldwin/Hawley exchange rate management bill is recognized in the Financial Times.

The novelty of an interventionist approach gains cross-party traction on Capitol Hill

[Brendan Greeley | August 19, 2019 | Financial Times]

Washington is beginning to sidle away from its two-decade consensus in favour of a strong dollar.

Donald Trump’s recent complaint that he was not thrilled with “our very strong dollar” because it harmed American companies has found fertile ground among some politicians on both sides of the aisle, and political momentum is building behind the idea that intervention might be necessary.

Republicans are more willing to contemplate interventions in the free market, Democrats have become unmoored from Wall St — which sells dollar-denominated stocks and bonds — and everyone is looking for ways to help domestic manufacturers.

The novelty of the idea is crucial on Capitol Hill; it leaves room for bipartisan experiments.

Last month two senators — one from either side of the aisle — co-sponsored a bill that would oblige the Federal Reserve to prevent the value of the dollar from harming US exports. The bill would give the Fed discretion over a “market access charge” to be levied on foreign investment in America — effectively a form of capital controls, historically regarded by US politicians as a radical economic measure.

Although the legislation has little chance of passing into law, it is an important symbolic moment in the shift away from the longstanding bipartisan consensus on the desirability of a strong dollar.

“Foreign speculators have driven up the dollar by trading in and out of US stocks, bonds and other assets,” said Senator Tammy Baldwin, the Democrat who co-sponsored the bill. “These trends have blown up our trade deficit and led to an uncompetitive American dollar.”

These are words that could have come directly from the president.

The bill would “level the playing field for our farmers and factories”, said Josh Hawley, her Republican colleague and co-sponsor of the bill.

Both Ms Baldwin and Mr Hawley are influenced by the work of Michael Pettis, whose 2013 book The Great Rebalancing championed the idea of weakening the dollar; their staffs have passed around a copy of the book.

Foreigners investing in the US are not contributing the capital that the country needs, Mr Pettis argued — instead the inward capital flows mean that other countries are pushing in capital they cannot use, creating economic distortions which damage homegrown industry.

His argument rests in part on the interest rate on federal debt, which is slowly dropping over time — a sign, he said, of demand for the paper exceeding its supply.

“If Americans were desperate for foreign capital, we wouldn’t get that capital by lowering and lowering interest rates,” he said. “We’d raise it.”

Weakening the dollar could help workers, midsized industry and farmers. Ms Baldwin’s bill originated with the Coalition for a Prosperous America, a trade group run by Dan DiMicco, a former steel executive who sits on the president’s advisory committee for trade.

It is backed by family-owned manufacturers, farming trade groups and representatives from the AFL-CIO and the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, both labour groups. They are all focused on the drag which a strong currency imposes on a nation’s industry and exporters.

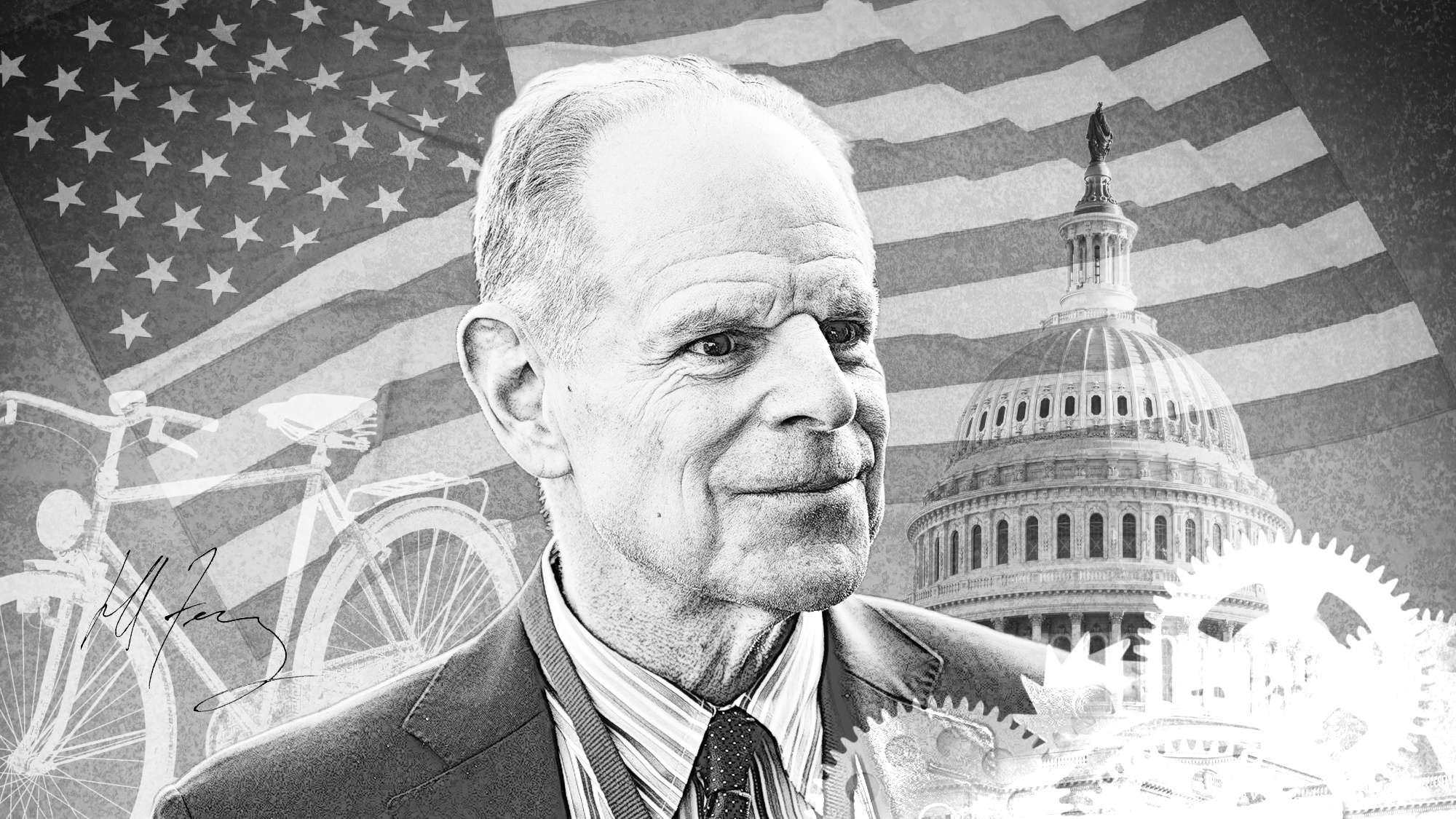

Jeff Ferry, the group’s chief economist, argued that to solve the problems of domestic manufacturers, “tackle the capital inflows. You don’t have to deter them all, you just have to deter enough to reduce the pressure on the dollar”.

The strong dollar has been unambiguously good for some, notably people who own and create dollar-denominated assets: financiers, property holders, and companies listed on US stock markets.

But perhaps it has now become a victim of its own success.

An explicit strong dollar policy was first officially endorsed by Robert Rubin, then Treasury secretary, in March 1995. At the time the Fed and other central banks were intervening to support the value of the dollar, the Federal government was paying more than 7 per cent to borrow and industrial production was growing at a pace that has seldom since been matched.

The risk of a dollar crisis — which would cut off the country’s ability to borrow abroad — was small, but it seemed more pressing than the possibility of a decline in manufacturing if the dollar rose too high.

“We were very focused on the dollar as the reserve currency,” Mr Rubin told the FT last week — and he would still make the same decision in 2019.

The strong dollar policy created capital inflows which in turn lowered the cost of capital, making it cheaper for American companies to borrow and raising the value of their stock, he said. The consistency of the strong dollar policy created “a kind of [investor] confidence that one should not sacrifice lightly”.

After a long bull market in stocks and with investment-grade companies borrowing at below 3 per cent, anxiety about the cost of capital seems less compelling. And now there is political appetite for sacrifice.

“Five years ago I would have thought it would take 15 to 20 years before anyone in Congress would understand,” said Mr Pettis. “And now we have a bill already.”

Read the original article here.