The president’s favorite numbers guy, Peter Navarro, says buying from China strengthens a potential enemy.

[Peter Coy] May 2nd, 2017 [Bloomberg Business Week]

As he stepped onto the stage at the annual meeting of the National Association for Business Economics, Peter Navarro knew he was facing a tough crowd—or what passes for one in the staid world of the social sciences. It was March 6, Day 46 of Donald Trump’s presidency, and Navarro, then the head of the newly created National Trade Council, was due to make a speech. His positions on trade have led many of his fellow economists to regard him as a traitor to their class. Navarro has a doctorate in economics from Harvard and has taught for more than 30 years at the University of California at Irvine’s Paul Merage School of Business, but he’s far more skeptical of free trade than many of his peers, for whom it’s not just another issue but a foundational principle. “Truly disappointing,” wrote Harvard economist Gregory Mankiw, who was President George W. Bush’s chief economic adviser for two years, in September of a Trump campaign white paper that Navarro co-wrote. It was the economist equivalent of a body slam.

At the NABE event, roughly 500 business economists had gathered at the Capital Hilton, a few blocks from the White House, to hear Navarro talk. “Good morning,” he began, an edge to his voice. The audience barely murmured. “It’s not church. Come on—good morning,” Navarro demanded. More murmurs. Giving up on that, he launched into his speech. The title, Do Trade Deficits Matter?, got right to the reason for the cool reception. Navarro argued that conventional economists think trade deficits don’t matter—and that they’re wrong. Trade is good, he said, but not when trading partners cheat.

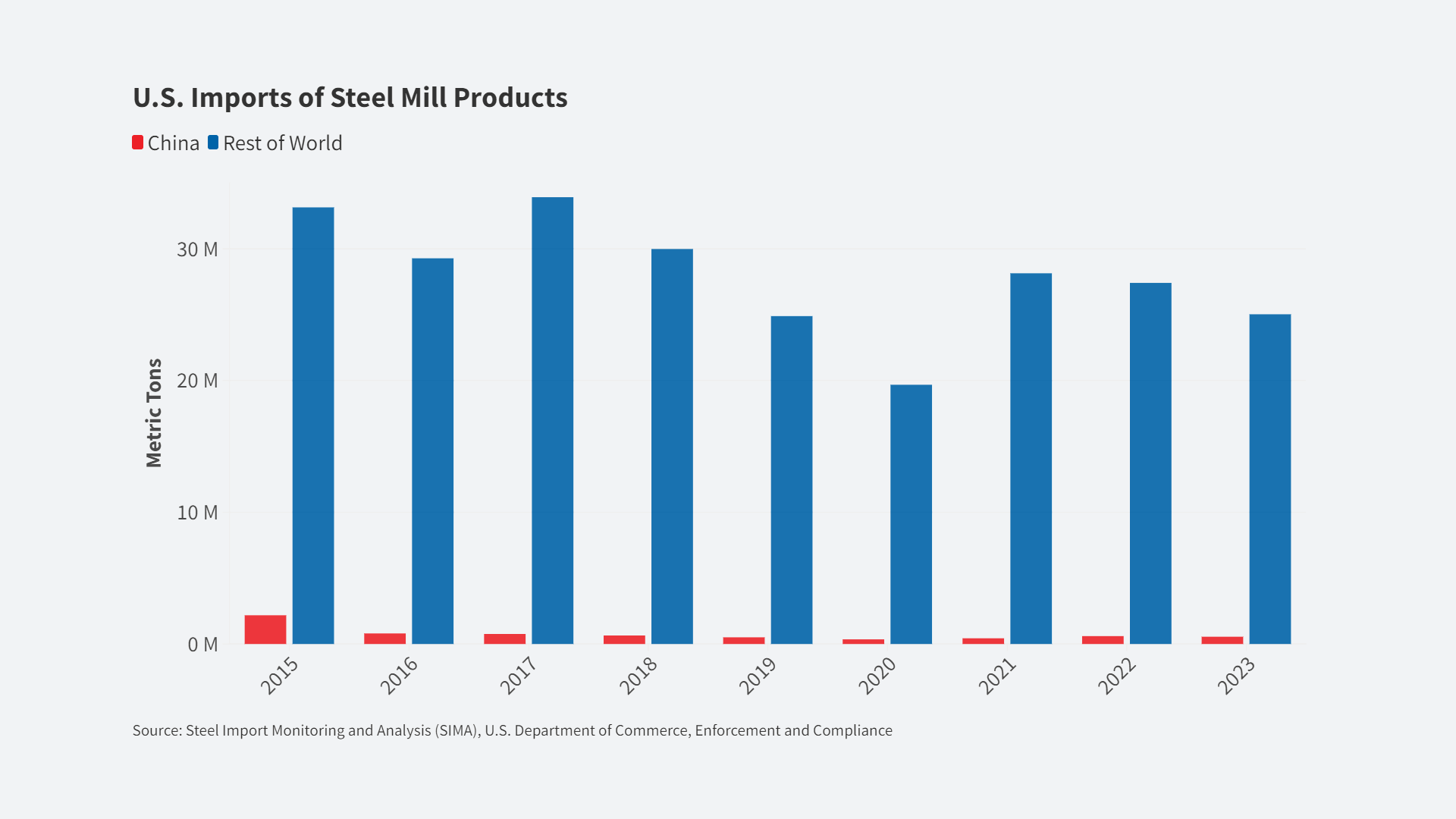

Countries that use dollars from trade surpluses to buy up American assets, he said, are pursuing a strategy of “conquest by purchase.” He added, “Most of those in our profession have chosen to ignore the broader national security risks that stem from large and persistent trade deficits and the concomitant decline of our manufacturing and defense industrial base.” Suppose, he told the economists, the acquirer isn’t an ally but “a rapidly militarizing strategic rival intent on hegemony in Asia and perhaps world hegemony.” The implication: Not only were the people in the room costing Americans their jobs, they could even get them killed.

After the speech, a bow-tied moderator, studiously neutral, read questions that were handed up from the audience. One defended the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the 12-nation trade deal that Trump backed out of after taking office. Navarro, incredulous, asked for the piece of paper the question was written on. “I’m saving this for my memoirs,” he said, condemning the TPP as “simply a bad deal” and a “death knell” for makers of autos and auto parts. “I’ll cherish this card,” he said. “Anyone want to own up to this one?” The room was sullen. It was a typically provocative performance from the man who appears to be Trump’s favorite economist.

Navarro doesn’t always get his way. He and the other nationalists on Trump’s team, including chief strategist Steve Bannon, contend with defenders of the status quo such as Jared Kushner, the president’s son-in-law, and Gary Cohn, the head of the National Economic Council. Which faction is winning can seem to vary by the news cycle. Trump, who before the election damned the North American Free Trade Agreement as “the worst trade deal maybe ever signed anywhere,” is now talking about mending it, not ending it. The president has shrugged off his campaign promise to declare China a currency manipulator “on Day One.” He even says he’s now open to making trade deals with China in return for its help with North Korea.

Navarro, who’s 67 and fit, with combed-back white hair, works out of a large corner office in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, where his stand-up desk faces the White House. During an interview in his office, Navarro got one sentence into recounting his biography—“I was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts”—when a call from Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross, the billionaire investor, came in on his cell. Ross is Navarro’s main conduit to Trump. He went out in the hallway to talk and didn’t come back for 20 minutes. When asked later about Navarro, Ross sent a restrained statement through a spokesperson. “Peter was a great help during the campaign.” He added a sentence about the administration’s intention to fix bad trade deals that made no mention of Navarro. When I told Navarro a few weeks later that Ross’s statement seemed lukewarm, he got Ross to send me a new one. This one said that since the campaign “we have continued to work closely together on Executive Orders and other projects.” Ross wrote that they often debated the details, but added, “This is a strong point of our relationship and a process that results in well-vetted conclusions.”

Navarro has been on a high recently. He’s spearheading the president’s nationalistic “Buy American, Hire American” initiative, which tightens enforcement of federal procurement rules and cracks down on alleged abuse of H-1B visas and other foreign-hiring programs. On April 29, Trump called Navarro “one of the greats at trying to protect our jobs” and named him director of a new, permanent Office of Trade and Manufacturing Policy, which replaces the National Trade Council. Trump’s condemnation during his campaign of various trade deals as “terrible” and “a rape of our country” seemed sincere, and he badly needs a win as president. If he’s stymied on health care and taxes, he could bang the drums on trade even harder. That would be good for his adviser. Navarro “could be down this week and back next week,” says William Reinsch, former president of the pro-trade National Foreign Trade Council. “As an adviser or counselor or whisperer in Trump’s ear, I suspect he won’t go away.”

Navarro would be intriguing even if he’d never joined the Trump administration, simply because he presents such a challenge to his profession’s mainstream. Since World War II, presidents and lawmakers of both parties have tended to heed the textbooks: Free trade encourages companies and workers to specialize, lowers prices, and keeps U.S. producers sharp; displaced factory workers should be able to find new jobs; if they fail, they can be compensated for their losses with a small share of society’s gains. In 2012, 95 percent of leading economists surveyed by the University of Chicago Booth School of Business agreed with the following statement: “Freer trade improves productive efficiency and offers consumers better choices, and in the long run these gains are much larger than any effects on employment.”

Voters never fully bought into that message, though, and they’re getting less deferential to authority figures. In 2013, according to a paper by economists at Booth and Northwestern University, 76 percent of the general public said “buy American” requirements have a positive effect on U.S. manufacturing employment. Only 11 percent of economists agreed.

Navarro is as skeptical of trade as the average blue-collar American, if not more. His 2011 book, Death by China: Confronting the Dragon—A Global Call to Action (written with Greg Autry), argues that the U.S. and China are on a trajectory for armed conflict. Trump blurbed a 2012 documentary film based on the book, narrated by Martin Sheen, as “Right on. … I urge you to see it.” The trailer features a knife, representing China, that’s plunged into a red, white, and blue map of the U.S. Blood leaks from the tricolor corpse.

A lot of Democrats don’t know what to make of the Trump-Navarro trade agenda. They may be turned off by the bluster, pugnacity, and flag-waving, but many share the sense that free trade has served multinational corporations better than ordinary Americans. Vermont Independent Senator Bernie Sanders said in January that he’d be willing to work with Trump on “a trade policy which works for the American worker.” In March the liberal Roosevelt Institute credited “right-wing economic authoritarianism” with co-opting aspects of the trade policy playbook of progressives, leaving them “struggling with whether to pivot right, left, or center on trade questions.” Robert Hockett, a Cornell Law School professor who was a spokesman for Sanders’s presidential campaign, says he finds a lot about Navarro to admire. “Mr. Navarro’s position on trade liberalization,” he wrote in an email, “can be viewed as representative of that of MANY Democrats and Republicans who initially bought into the promise that free trade would ‘lift all boats,’ only to be quite reasonably disillusioned.”

When Navarro was a child, his father, Al, played saxophone and clarinet and led a house band that did the hotel circuit—summers in New Hampshire and winters in Florida. “We lived out of a station wagon” part of each year, Navarro says. His parents divorced when he was 9 or 10, and his mother got a job as a secretary for a Saks Fifth Avenue in Palm Beach, Fla., raising him and his older brother on her small weekly paycheck. When the family moved to Bethesda, Md., a teenage Navarro worked as a stock boy and security guard, delivered the Washington Post, and pumped gas. He slept on a couch in the living room of the one-bedroom apartment. “That kind of upbringing makes you stronger,” he says. “You learn to survive on your own. I was a latchkey kid. By high school, I pretty much was cooking a lot of my meals.”

On Navarro’s first day at Bethesda-Chevy Chase High School, a guidance counselor “took one listen to my Southern accent and wanted to vocational-track me,” he says. “That’s the first I remember standing up for myself. I told him in no uncertain terms I would pursue an academic track.” He finished near the top of his class. Although only 5-foot-6 at the time, he played guard on the varsity basketball team, and he went to Tufts University with a full academic scholarship.

Back in the U.S., he briefly did consulting work, then earned a master’s degree at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, followed by a doctorate in economics, focusing on utility regulation. “I found my calling,” he says. He wrote a 1981 New York Times op-ed with one of Harvard’s most famous economics professors, Dale Jorgenson, that criticized a Reagan administration tax proposal as “a very large corporate subsidy.” He supported free trade in a 1984 book, The Policy Game: How Special Interests and Ideologues Are Stealing America, arguing that tariffs “protected the profits of a small core of domestic industries” while harming consumers. (He explains that because “the globalist erosion of the American economy” was just getting started, he hadn’t recognized it then.)

After earning his Ph.D. in 1986, Navarro moved to the northern edge of San Diego and in 1989 got a job up the coast teaching at UC Irvine’s business school. He reminisces about swimming two or three times a week in La Jolla Cove, surrounded by dolphins, and windsurfing on Mission Bay. He was troubled by what he saw as uncontrolled Los Angeles-style development beginning to destroy the idyllic area, spawning traffic, jamming students into prefab buildings, and spewing raw sewage into the ocean. He founded a group called PLAN—Prevent Los Angelization Now—which marked his entry into politics.

“Blond, brash, and charismatic” is how the Los Angeles Times described him in those days. Navarro ran for mayor of San Diego on the Democratic ticket in 1992, losing with 48 percent of the vote. He later lost elections for the county board of supervisors, city council, and the U.S. House of Representatives, selling himself as a Democrat who could win over Republican voters. One poster for his 1996 congressional race read, “Peter Navarro. The Democrat Newt Gingrich fears most!”

As the force behind PLAN, he infuriated developers by fighting their projects while saying he supported growth. “How is it that someone who has been so contradictory can get away with those contradictions and not be dismissed as an inconsequential leader?” asked Robert Lichter, a shopping center developer who was informally designated by his peers to do battle with Navarro at the time.

Reached by phone in March, Lichter says he was stunned that a man who’d campaigned to restrain development was working for President Trump, the world’s most famous property developer. “When he came into town, nobody knew who he was,” Lichter says. “Somehow he ended up making a name for himself. He had a winning smile. He had the Redford white teeth. … He was really not a friend of business, which is interesting when you consider today,” says Lichter, who calls himself an avid Trump supporter. “When we opened the paper and first saw his name as an adviser to Trump’s campaign, I went, ‘Oh, my God, Peter, how did you pull this one off?’ I would never in a million years have imagined it. It is the antithesis of the Peter Navarro I knew.”

Aside from a leave of absence during the mayoral race, Navarro kept teaching at UC Irvine during his campaigns, which ended with his fourth loss in 2001. In the 2000s he began churning out investing and management titles for a general audience such as If It’s Raining in Brazil, Buy Starbucks (2004), which advised mom and pop investors to trade on macroeconomic events, and What the Best MBAs Know: How to Apply the Greatest Ideas Taught in the Best Business Schools (2005). His distaste for free trade had begun to emerge as early as 1993, when he wrote a book praising President Clinton’s agenda—except for Nafta, which he took to calling Shafta. Navarro says his concerns grew in the mid-2000s, when he noticed that some of his evening students were being displaced from their day jobs in management. “At the time, I didn’t know what the cause was,” he says, “so I started asking questions, and all roads seemed to lead to Beijing.”

He concluded that China’s competitive advantage wasn’t just from lower wages, which would be a fair fight, but from unfair trading practices such as illegal export subsidies, currency manipulation, and theft of intellectual property. He wrote The Coming China Wars: Where They Will Be Fought, How They Will Be Won in 2006 and then Death by China, the book that caught Trump’s attention, in 2011. Navarro made another intellectual leap in 2015 when he ventured from trade economics into military strategy with Crouching Tiger: What China’s Militarism Means for the World. He warned that neoisolationism toward China was tempting but dangerous: “If this head-in-the-sand trend continues, this is a story that can only end badly for all of us.”

Navarro’s critics point out that despite his Ph.D. from Harvard, he has no scholarly credentials in the field of trade. He did team up with one widely published scholar—Glenn Hubbard, the dean of Columbia Business School and former chief economic adviser to President George W. Bush—for a 2010 book called Seeds of Destruction: Why the Path to Economic Ruin Runs Through Washington, and How to Reclaim American Prosperity, which was billed as a bipartisan blueprint for reform. When asked after Navarro’s NABE speech about that collaboration, Hubbard said, “You won’t find much of the rhetoric you heard this morning in the book.”

Navarro says he’s well-versed in classic trade theory, dating to David Ricardo in the early 1800s, because he teaches it: Countries, like people, should produce what they’re best at and import the rest, yadda yadda yadda. “I know how it works, but more importantly I know how the Ricardian trade model doesn’t work,” he said in an August interview with Bloomberg.

He blames Nafta and China’s 2001 entry into the World Trade Organization for much, if not all, of a 15-year economic slowdown in the U.S. The country grew an average 1.8 percent a year during that span, down from 3.4 percent from 1986 through 2000. Other economists cite a wider range of causes for the deterioration, from a productivity slowdown at home to cheap-but-legal competition from the developing world. Not Navarro. “Bad trade deals are at the heart of America’s economic malaise,” he says. “Trump knows that in order for the global economy to prosper, we need to trade freely. But he’s not going to stand, for a second, cheating.”

Last August, Trump named Navarro to a 13-member economic policy advisory team along with powerful finance types such as hedge fund billionaire John Paulson. In December the president announced the National Trade Council and said Navarro would be the first person to head it. Navarro was given one employee, Alexander Gray, who specializes in the defense industrial base and shares the office at the Eisenhower building. They haven’t bothered to decorate, other than a couple of maps and a moody Ogden Pleissner painting from 1940 of an auto plant converted to a ship factory. Attached to the White House-facing wall are three poster-size sheets on which Navarro has scrawled to-do lists in red marker. On the floor next to the door are two pairs of running shoes, which he wears for running to work and then home again.

Rare speeches aside, most of what Navarro does involves planning Buy American, Hire American; assisting Ross and others in prepping for bilateral trade negotiations; and helping companies, workers, farmers, and ranchers injured by unfair foreign competition. Right now that includes Whirlpool Corp.’s fight with South Korea’s LG Electronics Inc. and Samsung Electronics Co., which he accuses of “country-hopping”—changing manufacturing locations to avoid penalties for dumping products into the U.S. at below cost. (Samsung says it respects U.S. trade rules. LG didn’t respond to a request for comment.) The cases are referred to him by the Department of Commerce. “The best problems that come in for our SWAT team to solve are specific problems of an entity that can be generalized to a macro solution,” Navarro says. As for White House infighting, nationalists vs. globalists is “a false narrative and a false dichotomy,” he says. “It doesn’t capture the sophistication and nuance of the way the team works together.”

To be fair to mainstream economists, Navarro’s portrayal of them as clueless theoreticians is a straw man. Many would agree that running chronic trade deficits can permanently undermine a country’s production capacity while leaving it beholden to foreign creditors. Where they part with Navarro is over what to do about it. He and Trump convey more willingness to risk trade wars. They favor bilateral negotiations, in which they presume the U.S. has more bargaining power. But they’re wrong to think that other countries will fold under strong U.S. pressure, says Reinsch, the pro-free-trader who’s now a distinguished fellow at the Stimson Center, a Washington think tank. “In a lot of countries, standing up to the Americans is good domestic politics, whether it makes economic sense or not.” By retreating from multilateralism, the U.S. could play into China’s hands, some free traders argue. The vacuum left by the TPPcould soon be filled by the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, behind which China is the driving force.

There are still free traders who would like to dismiss Navarro as a Don Quixote tilting at Chinese-made wind turbines. That would be a mistake. He’s saying what a lot of people are thinking—including, it would seem, the president. He’s also on the same side as some of the most influential figures in the creation of America. Abraham Lincoln was an ardent protectionist. Alexander Hamilton, the first Treasury secretary, favored tariffs and subsidies to build a strong domestic manufacturing base. Scott Paul, the president of the Alliance for American Manufacturing, an industry group, says Navarro is squarely in that tradition: “Peter,” he says, “is a Galileo or a Copernicus.”

In an email, Navarro shared several lessons from politics: “Pick battles big enough to matter and small enough to win.” “Get back up every time you get knocked down.” And, sounding Trump-like, “You have a lot more ‘friends’ when you win than when you lose.”

“My mission in life has been to look at big problems that matter,” Navarro says. “I don’t like labels, and I don’t like to put myself in any category other than a pragmatist.”