Editor’s note: This opinion article by the former chief of staff of Vice President Joe Biden shows how the battle lines on the US-Mexico agreement, like much of the president’s trade agenda, are atypical.

Reading some of the reporting on the preliminary NAFTA renegotiation deal announced Monday between the United States and Mexico, there’s a partially unwarranted theme emerging: President Trump is a hypocrite because he’s now endorsing a deal that’s largely the same as the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a deal he vehemently opposed.

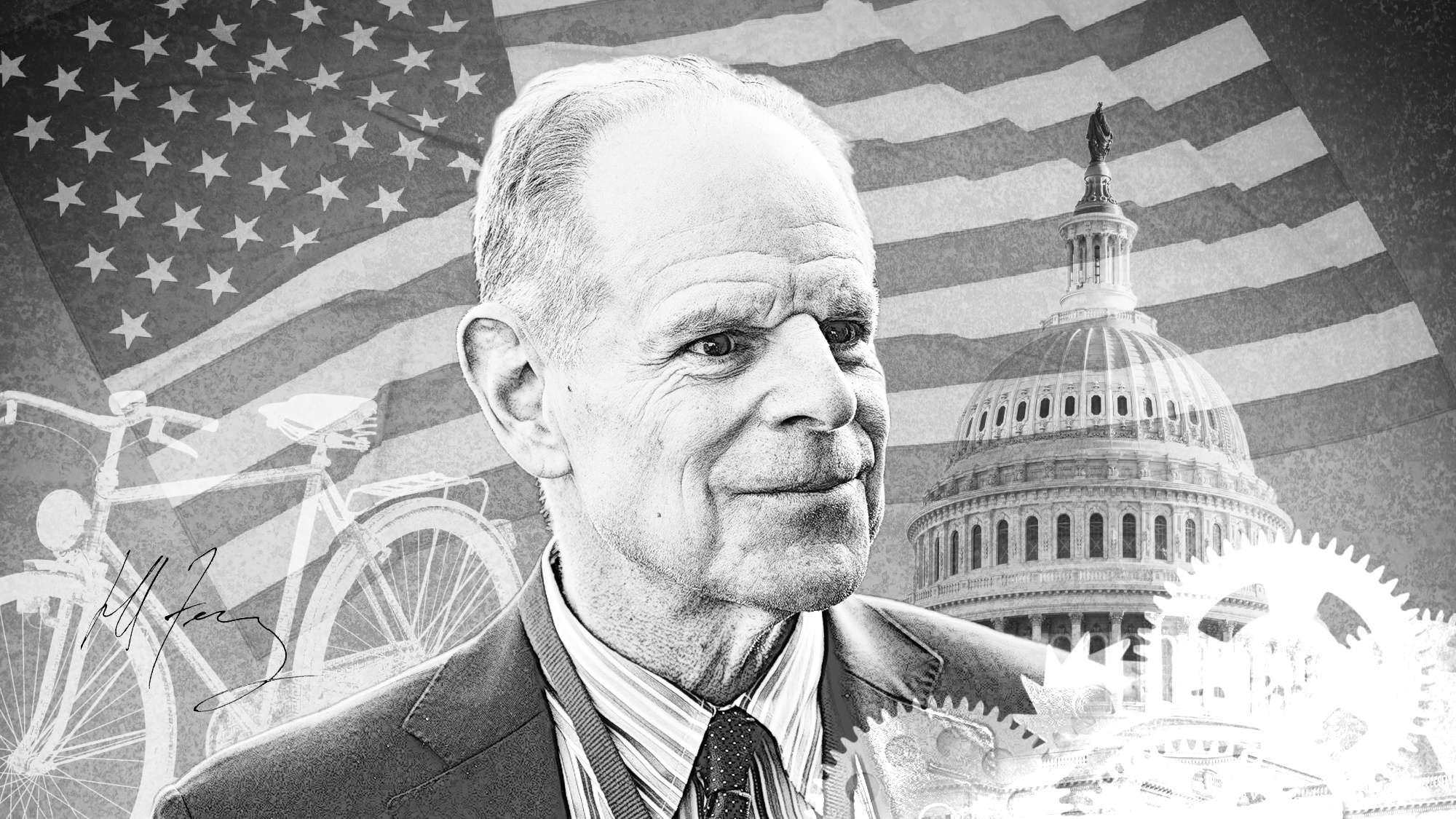

[Jared Bernstein | August 28, 2018 | Washington Post]

That’s partly right: Trump’s a hypocrite. But from what we can tell, this preliminary Mexican deal looks very different, and better for both American and Mexican workers then TPP ever did.

One big reason this TPP analogy is wrong is that the highly problematic investor-dispute process that was in both the NAFTA and the TPP is much altered and improved in this new framework. That alone, if it sticks, totally undermines the false equivalency.

Under Chapter 11 in NAFTA, disputes between investors in the member countries were resolved not by the courts of the member countries but by a tribunal of three lawyers empowered to order unlimited sums to be paid to the investor from taxpayers for any domestic policy or action that the investors claim violates their rights and privileges under NAFTA.

The rationale for this process, called investor-state dispute settlement, or ISDS, is that absent some form of protection, investors would, not unreasonably, fear that their rights would be violated in countries with inadequate legal systems. But the reality is that in 25 years of NAFTA, corporations have grabbed $392 million from taxpayers in investor-state attacks on environmental and health laws.

ISDS never made sense between the United States and Canada, which have legal systems as advanced as any in the world. And yet, according to Lori Wallach, who knows more about these deals than almost anyone, “54 of the 56 NAFTA ISDS cases to date attacking U.S. or Canadian laws were brought by investors from the Canada or the U.S., not from Mexico,” suggesting that investors were using the process to avoid legitimate, sovereign, highly functional legal systems

The new deal, according to Wallach, “eliminated the old NAFTA ISDS text altogether and ends the possibility of any future U.S.-Canada ISDS cases. This is huge, given major U.S.-Canada cross investment.”

For Mexico, where domestic courts are less reliable, investors who have an investment dispute with the government must first exhaust domestic court and administrative remedies or spend 30 months trying to do so, before turning to new procedures that significantly raise the bar to investor compensation.

Under this new system, there is no “right to invest” as exists in TPP and NAFTA, implying no investor rights to demand compensation if a government decides, for instance, to ban fracking or not authorize the digging of a mine. Compensation is available for direct expropriation, not the broad set of special rights provided investors in NAFTA and TPP. (The fact that the Business Roundtable is already complaining about this part of the deal is revealing in this regard).

There is apparently a carve-in for broader rights for the relatively few existing concessions contracts in Mexican oil and gas made in the past few years that this sector was partially privatized. These terms would allow a small group of U.S. investors the same protections as in earlier agreements if Mexico continues to provide those rights to other countries’ investors. This caveat looks to have been the negotiating price for the larger advances just noted.

Turning to labor standards, I find nothing in the TPP that comes close to the 75 percent regional auto content, including parts, up from about 62.5 percent under NAFTA. TPP’s auto content rules were set at 45 percent, meaning most of the value of a vehicle could be sourced from China and still have obtained TPP treatment.

An even greater standards improvement is the requirement in the U.S.-Mexico deal for $16 an hour pay for 45 percent of auto-production content and 40 percent of auto parts content; that’s about four times what Mexican auto parts workers currently make and twice the earnings of those in Mexican auto assembly plants.

And unlike the TPP’s weak labor chapter and NAFTA’s entirely unenforceable labor side agreement, the United States and Mexico have agreed to labor standards that union folks consider excellent. This includes a new commitment in the agreement by Mexico to ensure secret-ballot votes by workers at a facility to choose unions and approve contracts. This would mean the end to the scourge of the endemic Mexican “protection” unions, which sign low-wage contracts with the boss before the first worker is hired.

That said, there’s a huge caveat on the labor chapter of the new deal: Enforcement is not yet sufficient. And even the best standards won’t change conditions on the ground unless swift and certain enforcement is guaranteed.

Predictably, these improvements in Mexican labor standards and the pulling-back of the investor privileges has commentators complaining about higher prices. But this reveals a fundamental misunderstanding about trade agreements: that their sole goal is to reduce consumer prices. If that were the case, the agreements wouldn’t include patent and IP protections that add hundreds of billions to consumer costs. Such protections for pharmaceuticals in the TPP led various physician groups and health-care advocates to oppose the agreement (they’re in NAFTA, too, of course).

But as Wallach and I have written, trade deals are largely about how the benefits of trade, which are real and substantial, are distributed. ISDS and patent protections serve the investor class, which isn’t surprising, as they’ve had the dominant seats at the trade-deal table for decades. It thus betrays a deep class bias to complain about labor standards and not investor protections. In fact, from a progressive perspective, one reason to engage in trade deals is to improve labor, consumer and environment standards, something that has long been part of the U.S. rhetoric but hasn’t been present enough in the deals themselves.

As noted, enforcement is a concern about this new framework. Absent strong enforcement language backed up by real oversight, there’s no reason to believe these higher standards will come to fruition. And of course, there’s a very long way from where we are with this deal to anything final.

But my point here is not to suggest I know where the NAFTA process is going. It’s to take down this phony, false equivalence between the deal we’re learning about and prior deals, including the TPP. With the enforcement caveats I’ve stressed, this deal looks to go a lot further toward helping workers on both sides of the border.