KEY POINTS

- U.S. pharmaceutical imports have risen sharply in the last decade, with imports from China and India skyrocketing.

- India and China are increasingly the leading U.S. source for generic pharmaceuticals, which account for 91% of all prescriptions written in the U.S.

- China and India account for 57.6% of total pharmaceutical imports by weight last year.

- Imports continue to rise rapidly, accounting for 32.8% of Americans’ total annual spend on pharmaceuticals.

- Growing U.S. dependence on China and India for widely-used generic pharmaceutical products creates serious risks to national security and patient safety.

- Generic drug shortages have led to unnecessary suffering for cancer patients and extended outbreaks of syphilis.

- There are some 100 drugs prescribed in the U.S. whose supply is dependent on a single factory in China.

- The PILLS Act would incentivize manufacturers to invest in U.S.-based generic drug manufacturing, increase secure supply of generics, and reduce U.S. dependence on supplies from China.

Pharmaceutical imports rose again in 2023, and continue to be the second largest import category for U.S. consumer goods. At $208 billion worth of imports last year, pharmaceuticals are gaining quickly on motor vehicles, and likely to surpass them in a year or two.

At the same time, pharma imports from China and India increased their share of total pharma imports, reaching 58% by weight. While imports from those two countries dominate the $208 billion in total imports, their dominance is much greater in specific drugs and medicines, sometimes reaching 100%. In many cases, pharmaceuticals from India are dependent on ingredients or starting materials that come from China. Our increased reliance on very few suppliers who ultimately depend on ingredients from China for many life-critical products is a huge risk to the health and safety of the American people.

Table 1 shows America’s top ten sources of pharmaceutical products last year by weight. China led the rankings, with 217.2 million kilograms (kg) or 477.8 million lbs of pharmaceutical imports. India came second with almost 180 million kg or 395.8 million lbs. Together these two countries accounted for 57.6% of U.S. pharmaceutical imports.

Table 1: Top Ten U.S. Sources for Pharmaceutical Imports by Weight 2023

| Source | Imports 2023 (kg) | Share of Total Imports (%) | |

| 1 | China | 217,224,446 | 31.5% |

| 2 | India | 179,910,580 | 26.1% |

| 3 | Germany | 38,899,115 | 5.6% |

| 4 | Italy | 26,304,262 | 3.8% |

| 5 | Spain | 24,169,277 | 3.5% |

| 6 | Switzerland | 24,062,952 | 3.5% |

| 7 | France | 19,853,500 | 2.9% |

| 8 | Ireland | 19,780,522 | 2.9% |

| 9 | United Kingdom | 13,690,196 | 2.0% |

| 10 | Israel | 12,455,212 | 1.8% |

| World Total | 690,456,126 | 100.0% |

The pharmaceutical industry is divided into two very different sectors: generic pharmaceuticals account for 91% of prescriptions written but only about 16% of revenue in the industry. Branded pharmaceuticals account for less than 10% of the prescriptions but over 80% of the revenue. The full price of a branded pharmaceutical like Johnson and Johnson’s Darzalex for blood cancer or AbbVie’s Humira for rheumatoid arthritis is around $3,000 for one week of treatment and well over $100,000 for a year. Generics on the other hand are cheap. A week’s course of generic antibiotics can cost less than $20.

The very high profit margins on branded drugs have enabled drugmakers to manufacture those products in the U.S. or Europe. European governments, especially the Irish government, have used subsidies and tax breaks to lure global pharmaceutical giants to manufacture there. The result is that Ireland is the number one source by dollar value for U.S. pharmaceutical imports (Table 2).

The intense pressure to lower prices of generic pharmaceuticals has led to a different global structure. Generic production has moved increasingly to India and China as the lowest-cost manufacturing centers in the world. Both countries have used government subsidies, export incentives, and other tools to lower their costs of production and build locally-owned drug manufacturing centers.

The offshoring of production to China and India has put the U.S. in a dangerous position, dependent on unreliable suppliers. Chinese and Indian manufacturers have demonstrated a pattern of repeatedly violating FDA regulations. FDA inspections are ineffective at controlling quality standards at Chinese and Indian facilities. The rise of drug shortages, the unreliable quality of the output of Chinese and Indian facilities, and the increasing concentration of the industry to one or two manufacturers for many drugs or key ingredients raises real questions over the FDA’s ability to address the shortage problem.

This import dependence is unsustainable. FDA Commissioner Robert Califf admitted as much last year, when he warned that “there’s not enough reserve and supply” of generic drugs in the United States. Califf admitted that the stakes are too high (i.e. patients are sicker for longer and some are even dying due to drug shortages) he said the economics of the industry need to be altered to boost domestic production of generic drugs.

Table 2: Top Ten U.S. Sources for Pharmaceutical Imports by Value 2023

| Source | Import Value 2023 | Share of Total Imports (%) | |

| 1 | Ireland | $ 51,503,272,405 | 24.7% |

| 2 | Germany | $ 20,059,209,071 | 9.6% |

| 3 | Switzerland | $ 15,785,918,123 | 7.6% |

| 4 | India | $ 11,265,075,102 | 5.4% |

| 5 | Netherlands | $ 10,798,763,813 | 5.2% |

| 6 | Italy | $ 8,793,843,040 | 4.2% |

| 7 | China | $ 7,796,469,903 | 3.7% |

| 8 | United Kingdom | $ 7,708,937,686 | 3.7% |

| 9 | Canada | $ 6,251,182,079 | 3.0% |

| 10 | Denmark | $ 5,832,590,642 | 2.8% |

| World Total | $ 208,546,915,612 | 100.0% |

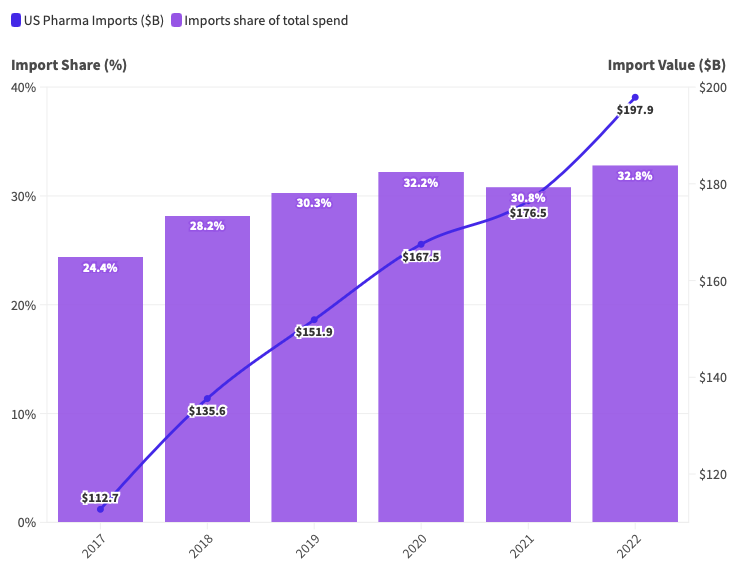

Increased offshoring of drug manufacturing has made imports a growing share of the U.S. pharmaceutical industry. In the five years from 2017 to 2022, imports rose to $197.9 billion, worth almost one third (32.8%) of the cash spent by American patients, insurers, hospitals, and the government on pharmaceuticals (Figure 1). On current trends, the value of imports and their share in the total pharmaceutical spend is likely to continue to rise.

Figure 1. In 2022, imports accounted for 32.8% of Americans’ spend on pharmaceuticals.

Generic Drug Shortages Increasing

Offshoring of generic drug manufacturing has brought with it many other problems. As hospitals and insurers seek to drive down the price of generic drugs, the process has pushed generic manufacturing into the hands of fewer and fewer companies, with an ever-larger percentage of them in India and China. This has led to widespread drug shortages.

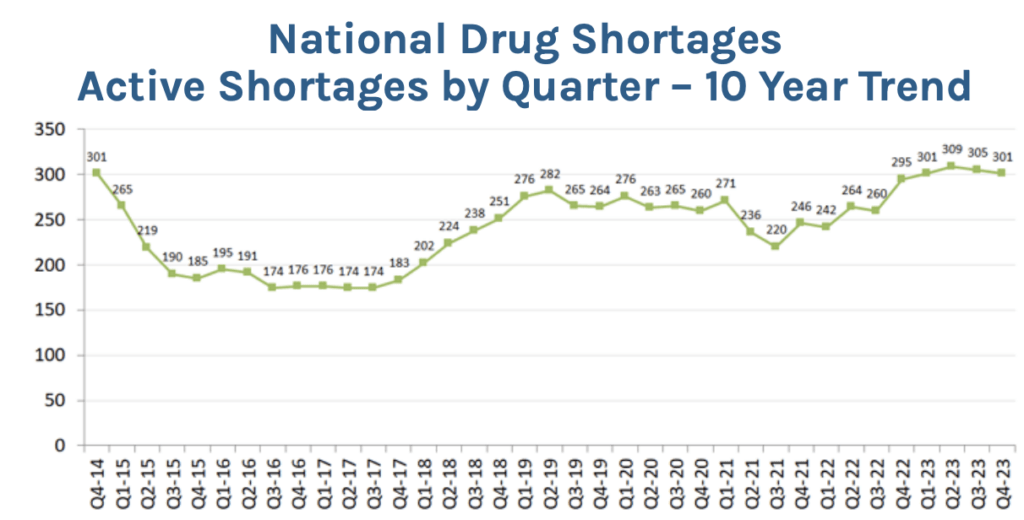

Data from the American Society of Health System Pharmacists (ASHP) shows that the number of drugs in shortage reached 301 at the end of 2023, one of the highest figures since data began. Note that the ASHP data is different from Food and Drug Administration (FDA) data. The FDA produces smaller figures because they count only shortages at the national level. The ASHP considers regional and local shortages too, a measure that doctors and health economists consider more relevant to the quality of care provided to patients. Figure 2 shows the rising trend of drug shortages since 2016.

Some of the most damaging shortages are in generic cancer drugs, widely used to control many forms of cancer. Two of the most widely used cancer treatments, cisplatin and carboplatin, have been in shortage for much of the past two years. A chilling study last year by the American Cancer Society found that one in ten patients have suffered from drug shortages. One cancer patient wrote this in reply to the survey: “My doctor office only gets enough for one patient a month. I’m currently set to get mine in over six months.”

Last year, the FDA allowed the cancer drug cisplatin to be sold in the U.S. from an uninspected lab in China. Faced with shortages and a limited number of suppliers, almost all of them overseas, the FDA is actually being forced to relax its standards, just to find any supplier of certain badly-needed drugs.

Figure 2: National drug shortages reached 301 at the end of 2023.

Source: ASHP

Doctors regularly write angry letters to newspapers complaining that they cannot find the drugs their patients need. It’s widely acknowledged that our generic drug supply system is broken. The heart of the problem is that we have driven prices too low, moved supply of generic medicines to a small number of the cheapest-of-the-cheap offshore suppliers, and sacrificed resiliency, manufacturing quality, and backup supply to chase the false god of low prices.

National Security

On top of all these problems is the large and growing national security risk as more and more drugs become dependent on suppliers from China. Even the common knowledge that we are becoming dependent on a small number of large drug companies for generic drugs understates the dependency on China. Data from Qyobo provides an illustration. Qyobo is a software startup that collects pharmaceutical data from dozens of national and international databases to provide a picture of the drug supply chain that is not only superior to what the patient or the doctor sees, it is probably superior to the knowledge of the FDA.

Take atorvastatin calcium. This is a statin or blood-thinner used by millions of patients at risk of cardiovascular disease. According to Qyobo’s data, atorvastatin is available from nine different drugmakers, including companies based in Germany, Bangladesh and Turkey. But all of those drugmakers depend on an Indian company, Ind-Swift Laboratories Ltd, for the active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) to make atorvastatin. And Ind-Swift depends on five companies, all of them Chinese, for the key starting materials (KSMs) to make the APIs. Unknown to American doctors or patients, the entire supply chain for this drug depends on China. Shortages of atorvastatin have been reported in the U.S., the U.K., and Canada.

Another example is in contrast dyes, which are administered to patients before CT scans to improve health care professionals’ visibility of the circulatory system and help identify blood clots in cancer patients. As a result of Covid-related factory shutdowns in Shanghai, China in early 2022, GE Healthcare was unable to produce enough contrast dye to supply the American market. According to a CNN report, about half the hospitals in the U.S. rely on GE Healthcare for the contrast dye. Vital scans were postponed or denied to patients at many hospitals as doctors and radiologists scrambled to find dye, used only in the most critical cases.

Last September, the FDA approved Chinese company Hainan Poly to manufacture Iopamidol, a contrast dye that was to be imported from Europe in order to address the contrast shortage. According to FDA records, Hainan Poly has not been inspected since September 2019.

Still another example is the antibiotic benzathine penicillin, which is now on shortage. It is the primary treatment for syphilis. According to an article in medical journal International Health, its production is entirely dependent on three Chinese API manufacturers. The shortage is said to be due to a combination of manufacturing constraints and unexpectedly increased demand. The true causes are always somewhat obscure because pharmaceutical companies try to conceal the thinness of their supply chain and its exposure to single points of failure, such as unexpected decisions by foreign governments to shut a facility.

Whatever the cause of the benzathine shortage, Professor Stephen Schondelmeyer says that it has led to more outbreaks of syphilis in the U.S. than were expected. Syphilis outbreaks affect disproportionately lower-income groups and pregnant women. Schondelmeyer, a professor of pharmaceutical management and economics at the University of Minnesota, testified on drug shortages before the House Ways and Means Committee in February, urging the Congress to take action to address the growing problem of generic drug shortages.

Professor Schondelmeyer told us that the U.S. is now dependent on India for 45% of the generic medicines we buy. One key reason generic drug production moved (and is still moving) to India is the high level of subsidies offered by the Indian government to drug manufacturers and exporters. Those subsidies are described here. Another reason is that India has not joined the International Council for Harmonization, a body that sets global standards for drug production. The U.S. and most European nations are members but India has refused to join. It also does not have national standards for drug production, instead leaving pharmaceutical regulation to its 38 states. That leads to widely differing standards across India, with the temptation to lower standards to attract more manufacturers. “The Indian drug industry is like the wild west on steroids,” Professor Schondelmeyer told us.

At the same time, the Indian pharmaceutical industry is highly dependent on China for APIs and KSMs. Says Professor Schondelmeyer: “There are about 100 drugs [dependent on ingredients] that are only made in one factory in the world and that factory is located in China. It would take two to five years to rebuild that capability outside of China. If China decides to use its leverage, we would be in trouble.”

A recent CPA report on Aurobindo — an Indian generic pharmaceutical manufacturer that is the largest provider of generic drugs by prescription to the U.S. market — revealed that Aurobindo has substantial, alarming ties to Chinese companies sanctioned by the U.S. for working with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) military, or for human rights violations. Aurobindo has had numerous well-documented safety and quality issues, as well as instances of corruption and lack of transparency.

China has already demonstrated its willingness to use its economic leverage in peacetime with commodities like rare earths and graphite. If hostilities between the U.S. and China rose or if we entered a genuine military confrontation over Taiwan or another global hotspot, we would be at grave risk of seeing vital pharmaceutical supplies reduced or cut off entirely.

Solutions

CPA supports the Producing Incentives for Long-term Production of Lifesaving Supply of Medicines Act, known as the PILLS Act, which would provide corporate tax credits for pharmaceutical companies investing in U.S.-based manufacturing facilities. The bill was introduced last October by Rep. Claudia Tenney (R-NY). The bill uses the tax credit techniques of the Inflation Reduction Act to stimulate U.S. companies to invest in the production of APIs and finished doses of generic medicines in either pill or injectable form. The bill is supported by both Democrats and Republicans.

Professor Schondelmeyer favors creating what he calls “concentric circles” starting with the most at-risk drugs, which start with drugs produced in at-risk countries in only one factory, then move out to include those produced at multiple facilities or multiple countries and those in current shortage.

But just to begin to pursue that objective requires more information than the FDA has today. The FDA has pretty much admitted that it is ineffective at managing America’s generic drug shortage problem, pointing the finger at the drug and medical device makers. In May 2022, FDA Director Dr. Robert Califf admitted in congressional testimony that supply chains are too narrow and too dependent on single sources.

“The [medical devices and supplies] industry has fought us tooth and nail on requiring that there be insight into their supply chains,” Califf told Congress. “We’d like to be able to stress-test and prevent these things from happening, rather than waiting until they happen and then scrambling.”