For all his bullying, narcissism and self-contradiction, there is one point on which presumptive Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump cannot be criticized. In attacking our nation’s longtime free trade policies and deals, the real estate tycoon has brought necessary attention to a huge elephant in America’s policy room, one that’s run wild and must be stopped by the nation’s next leader.

[Clyde Prestowitz| May 26, 2016 |The Daily World]

While Trump’s been especially vocal on the topic, he’s far from alone in taking this stand.

Bernie Sanders, the self-described democratic socialist seeking the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination, has also decried the “disastrous trade policies” of the past 25 years.

In fact, even Hillary Clinton, who most experts expect to beat Sanders and face Trump in November’s general election, now says she opposes the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a free trade agreement that she, while secretary of state, described as the “gold standard” of trade deals.

This is a big shift. For the past 70 years, all presidential hopefuls have held up free trade as key to bringing about prosperity and peace to America and the world.

Now, following Trump’s lead, all this year’s candidates are saying Washington’s way of promoting trade has, in actuality, been quite perilous and has undermined American prosperity to the advantage of our trading partners.

What did Trump so presciently see?

First, he saw the problematic approach to trade policy taken by establishmentarians like Robert Zoelleck, a former World Bank president and deputy secretary of state, who in a Wall Street Journal op-ed this month argued for the TPP, which has yet to be ratified by Congress, by focusing on the impact America’s trade agreements have had on national security.

To insiders like Zoelleck, the main purpose of trade and globalization policy is not to enhance the incomes and welfare of ordinary Americans; it’s to shore up allies against Russia and stop the Chinese from doing what is never precisely articulated.

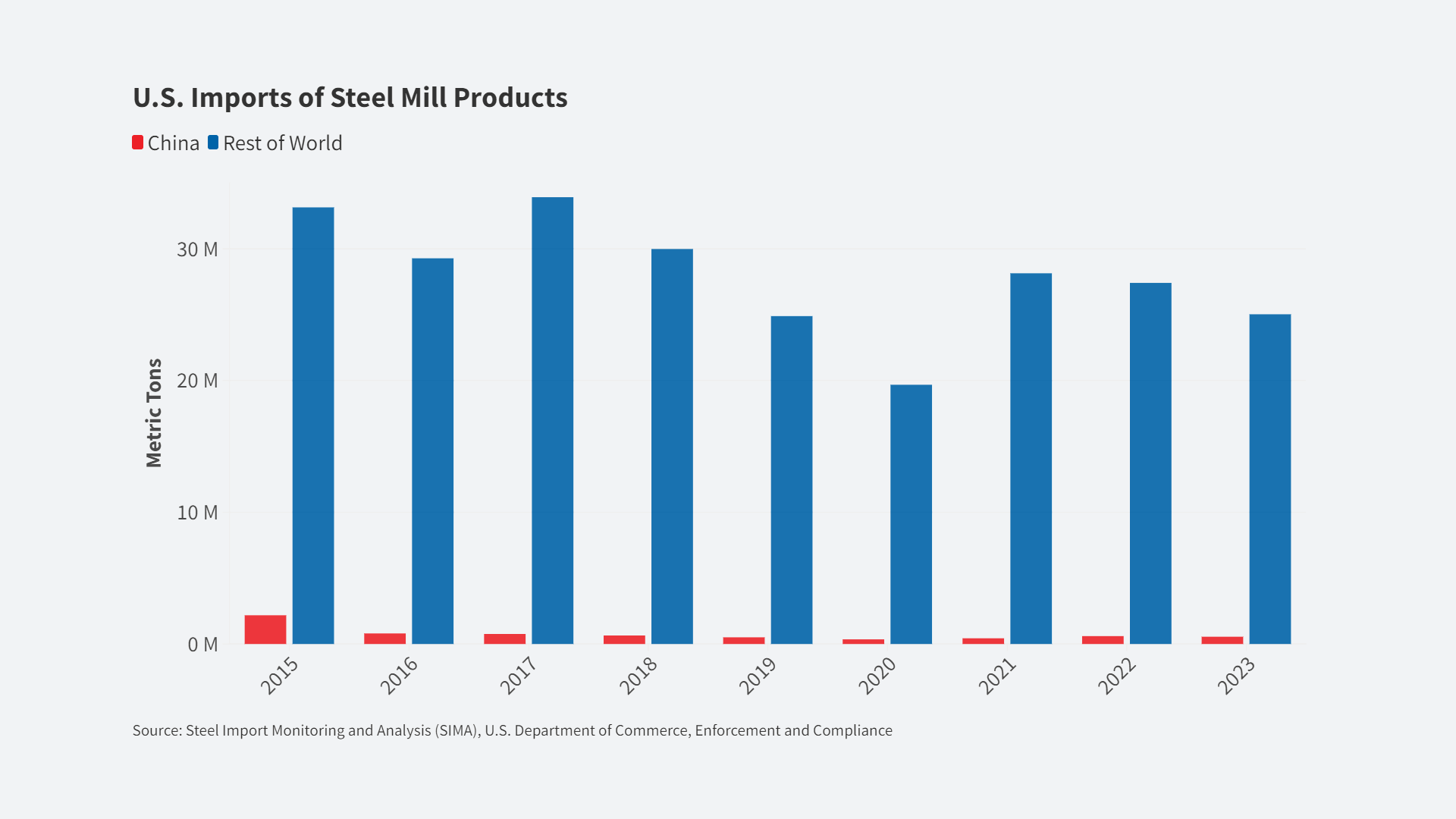

This position is held by the very people who uttered nary a whisper when General Electric, rather than investing back home, decided to move its high-tech aviation electronics division to Shanghai through a joint venture with a state-owned Chinese company. These are the people who promoted and profited from the offshoring of millions of American manufacturing jobs in the name of making China a responsible stakeholder in the global economic system.

To Trump, Sanders and those who share their view, such an approach is the height of inconsistency.

Neoclassical economists and the foreign policy establishment, however, see the nonreciprocal opening of American markets as an allegedly cost-free way of buying friends and persuading countries with tiny economies to host U.S. troops and join us in supporting supposedly critical issues at the United Nations.

This approach has long been thought of as cost-free because leading Anglo-American economists — not, mind you, Japanese, Korean, German or Singaporean economists — argued that free trade is always and everywhere a win-win proposition.

So, opening American markets to foreign competition, even when it’s been clear the competitors are operating under mercantilist, export-led growth policies, has been said to be a big win for the vast majority of Americans. Of course, it’s been admitted, there will always be a few workers or companies who suffer displacement, but it’s also been promised they’ll be compensated by the vast majority of winners. That’s how it’s been argued, anyway.

All this has been based on the counterintuitive concept of comparative advantage, first articulated in 1817 by British economist David Ricardo and elaborated upon in the 1930s by Swedish economists Eli Heckscher and Bertil Ohlin. The theory essentially holds that countries should concentrate on producing what they do best and trade for the rest.

What countries produce best, according the theory, is determined by their endowments of land, labor and capital. And therefore, countries like America, with skilled labor and lots of land and capital, ought to produce agricultural and advanced manufactured products and trade those for toys, clothing, and other products from countries with lots of cheap labor. America ought to sell computer chips and airplanes to China in return for T-shirts, underwear and lychees, the theory would say.

This all sounded good for a long time, but as noted in the early 1980s by economist Paul Krugman, this theory rested on a host of far-fetched assumptions: fixed exchange rates, no cross-border flows of investment or technology, constant full employment, no cost of entry into or out of business, no government intervention such as Social Security or minimum wages, no unions, and, very importantly, no economies of scale.

In other words, the world of free trade theory has always been make-believe, and increasing globalization made it more so.

Indeed, in the late 1990s, Ralph Gomory, a former chief scientist at IBM, and William Baumol, a former president of the American Economic Association, demonstrated that in the real world, where many countries and products were experiencing rapid technological change, immense cross-border flows of investment and technology, and frequent fluctuations in economic growth and employment, trade is as likely to be a zero-sum (I win, you lose) proposition as a win-win situation. The outcome of trade all depends on the situation, they concluded.

Trump and Sanders probably haven’t read all these analyses. But they have seen that none of the forecasts by Republican or Democratic administrations for new job creation and reduced trade deficits with Japan, China, Korea or other global partners ever came true. For instance, America’s $2 billion trade surplus with Mexico has turned into a $50 billion deficit since the North American Free Trade Agreement went into effect. Instead of shrinking, America’s trade deficit with China — which stood at $80 billion in 2011 — has ballooned to nearly $400 billion. America’s free trade agreement with South Korea has seen U.S. exports decline, imports double and 11,000 jobs quickly lost.

It’s hard to deny that Trump and Bernie have been right about trade.