Excerpt: Digital companies aren’t the only ones avoiding corporate taxes. Plenty of foreign multinationals that sell in the U.S. are also shifting profits through tax havens…

Over the past few months, a number of countries have been planning to impose new taxes on U.S. tech companies like Google, Facebook and Amazon. France in particular has aimed to impose “digital taxes” on these tech giants. The goal is to ensure that America’s tech firms finally start paying taxes on their massive global profits — rather than continue to hide earnings in tax havens.

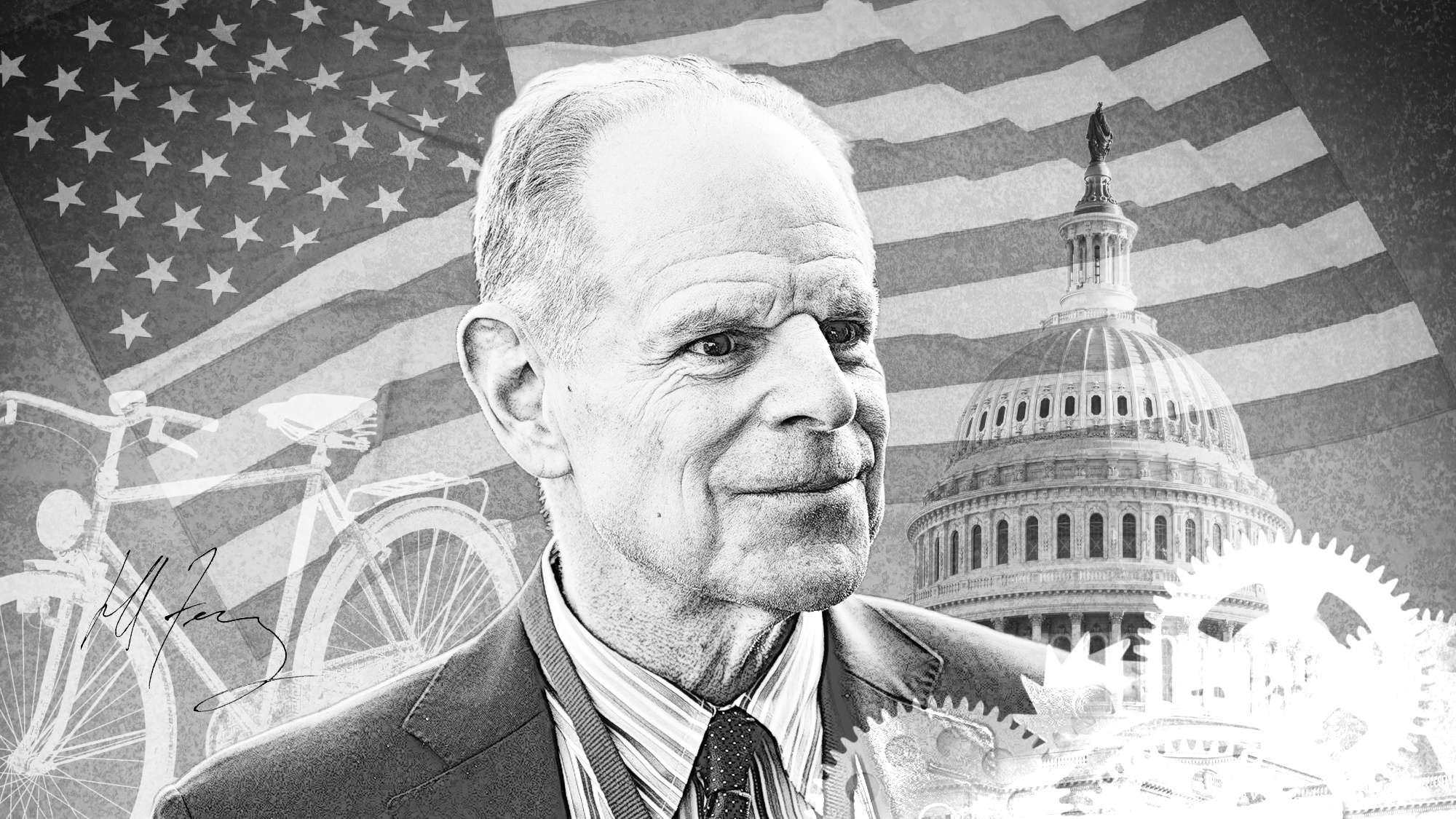

[David Morse | January 28, 2019 | Morning Consult]

Tackling this corporate “tax avoidance” has become a tense international issue of late. But last week, France and the U.S. agreed to a temporary truce — thanks to a major breakthrough between President Trump and French president Emmanuel Macron. Trump convinced Macron to delay any further digital taxes, and to wait until the conclusion of multilateral negotiations currently being conducted through the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

In the short term, this is good news for the large digital multinationals that would have faced higher corporate taxes in France and elsewhere. But it still leaves open a key challenge — the many multinational firms that similarly avoid paying corporate taxes in the U.S.

France’s proposed tax would have focused on America’s digital multinationals, like the aforementioned Google and Amazon. But it’s an extreme approach — since it wouldn’t hold French companies accountable for the same taxes these U.S. tech firms would be expected to pay. Worse, it would tax U.S. companies based on their overall revenue, without allowing for operating expenses.

Essentially, France proposed something akin to what’s known as a “destination-based tax.” That approach means taxing firms based on profits from their sales in a particular country. It’s a logical remedy to use, since it eliminates the effectiveness of tax havens. However, France’s approach — of imposing the new taxes only on specific industries and top-earning companies — would primarily target U.S. multinationals. As a result, it would hardly penalize French multinationals.

The president and congressional leaders rightfully objected to this one-sided plan. But digital companies aren’t the only ones avoiding corporate taxes. Plenty of foreign multinationals that sell in the U.S. are also shifting profits through tax havens. And U.S. tax policy simply does nothing to adequately address it. Should France or any other country end up imposing a destination-based tax on U.S. companies, Washington should use the occasion to respond similarly — and finally start taxing both foreign companies and multinationals through a similar destination-based system.

Right now, during the current cooling-off period, the Trump administration has time to consider a response — one that would assesscorporate tax liability based on profits earned from sales in the U.S. market. Doing so would mean any company — domestic or foreign — selling a product or service in the U.S. would finally be required to pay taxes on its profits, no matter where it might be “domiciled.”

To make this happen, President Trump should start right now to get a jump on things. He could direct the United States Trade Representative (USTR) to begin drafting a response. And Congress should follow suit with supporting legislation.

There’s little doubt that foreign multinational corporations continue to use tax avoidance to enjoy major profits from America’s lucrative consumer market. And they happily pay little or no taxes. It’s estimated that foreign and American multinationals avoid paying roughly $80 billion annually in U.S. corporate taxes — a windfall that gives them a clear advantage over smaller, domestic U.S. firms.

It’s a good thing that President Trump was able to negotiate a halt to France’s proposed digital services tax. But it’s unclear how long that will hold. Hopefully the current pause will buy enough time for the USTR and Congress to consider solutions to help domestic companies compete on more equal terms with overseas competitors, particularly the multinationals that continue to game the U.S. tax system. Otherwise, France’s digital services tax will lead to yet another scenario where U.S. firms are penalized, to the benefit of foreign competitors.

Read the original article here.

David Morse is the tax policy director at the Coalition for a Prosperous America Education Fund. Follow him on Twitter @CentristinIdaho.