The proposed acquisition of U.S. Steel by Japan’s Nippon Steel has understandably generated controversy and concern. At a gut-level, it feels wrong to many Americans.

President Biden says the acquisition deserves “serious scrutiny in terms of its potential impact on national security and supply chain reliability.” And former President Trump has pledged to block Nippon’s purchase if he retakes the Presidency.

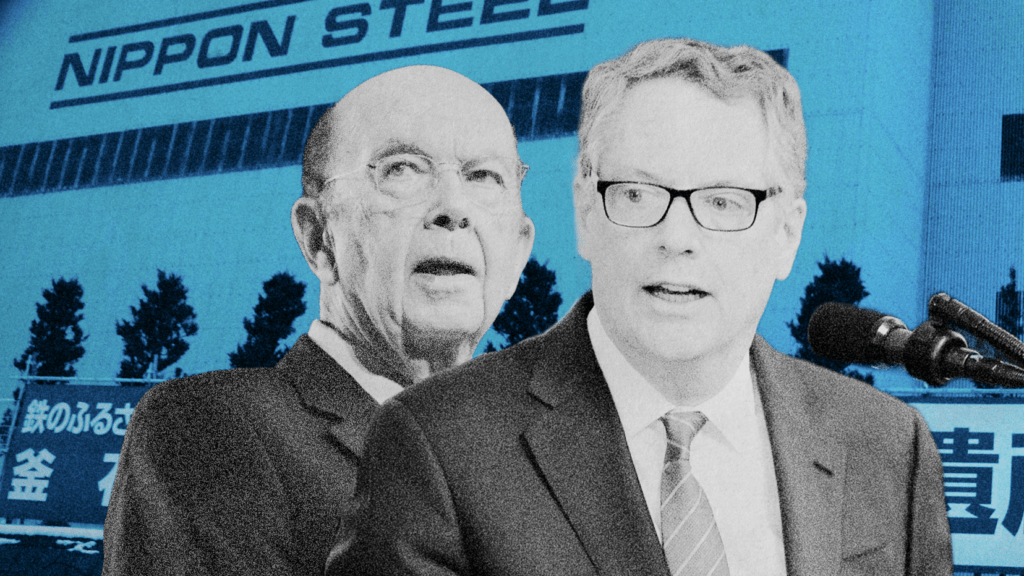

But Wilbur Ross, U.S. Secretary of Commerce under President Trump, wrote in a WSJ op-ed that only “xenophobia” or anti-competitive concerns were driving opposition.

Secretary Ross is wrong. He should listen to his former colleague and past U.S. Trade Representative, Ambassador Robert Lighthizer, to understand why.

The history leading up to Nippon’s takeover bid is a story of failure and inaction on the part of U.S. policymakers.

America has always welcomed ‘greenfield’ foreign investment from friendly nations, and Japan is a highly regarded U.S. ally. But while we welcome friendly foreign investment into new domestic productive capacity, we are also the country that invented antitrust law. We rightfully scrutinize mergers and acquisitions which limit competition.

Acquisition scrutiny should be magnified exponentially when a proposed acquisition targets American productive capacity and comes from a nation that runs persistent trade imbalances with the United States.

Why? Listen to Ambassador Lighthizer, who explains it better than anyone in his book, No Trade Is Free. The following is an excerpt (pp. 25-26):

Why Persistent, Long-term Trade Deficits Matter for the United States

The United States has run huge consecutive trade deficits for decades. All told, we have accumulated more than $11 trillion in trade deficits since just 2000. None of this is free. We are trading our assets for short-term consumption. Yet incredibly there is a debate about whether this matters. Ordinary Americans know on a commonsense level that deficits matter in life. If you make more than you spend, you get richer. If you spend more than you make, you get poorer. Only some economists seem to have trouble with this simple concept.

Free trade enthusiasts, and those influenced by their arguments, take comfort in the following trope: “I run a trade deficit with my barber; since both of us are better off as a result, even though he gave me no money back, this shows why trade deficits are benign.” However, a deficit with the barber is one thing, but if I run a deficit with the barber, the butcher, the baker, and everyone else, including my employer, the situation is altogether different.

Moreover, long-term trade deficits must be financed through asset sales, which can prove unsustainable over time. The man paying his barber can pay with a cash surplus, but what if he starts trading assets—that is, things he owns that he expects to lead to future wealth? The trade deficit that he runs with providers of goods and services he consumes is benign if it is offset by the surplus he runs with his employer through the sale of his labor. But the situation may prove unsustainable if he’s funding his consumption by taking out a second mortgage on his home. And that is essentially what the United States has been doing over the past three decades by running a trade deficit year after year.

Ambassador Lighthizer is correct that ordinary Americans have a better sense of the takeover attempt than free trade enthusiasts.

Ambassador Lighthizer continues on page 27:

As Warren Buffett pointed out in his famous 2003 article about “Thriftville and Squanderville” (“America’s Growing Trade Deficit Is Selling the Nation Out from under Us”), there is a compounding effect in huge trade deficits. That is something we could call negative compounding. The people in the foreign country who buy our assets own those assets forever, with the obvious effect that they get the profit from those assets year after year. That profit compounds, and the effects of even one year’s trade deficit multiply over time as profits continue. Added to this is the fact that we have seen huge $500 billion to $1 trillion trade deficits year after year, so we have both an accumulation of trade deficits and a compounding negative multiplier on each trade deficit.

So how big is the problem? There is something called the net investment position of a country. That is how much a country owns in all other countries (all-inclusive—stocks, bonds, real estate) compared to how much all other countries own in that country (all-inclusive). For the United States, it would be how much US citizens own around the world compared to how much foreign citizens own in the United States. It’s not a stretch to say that the country with the most positive net investment is the richest.

The net investment position of the United States was positive and very high for decades. Indeed, we were the richest country in the world by this measure for most of the twentieth century. In the last thirty years, however, that number has changed very dramatically. When Mr. Buffett made his complaint about our rising persistent trade deficits back in 2003, the negative net investment of the United States was about $2.5 trillion. It is now $18 trillion. In other words, foreign interests own $18 trillion more of American debt, equity, and real estate than we own within them. That means that their children will receive and can invest all of that wealth and that our children cannot. With $18 trillion, you could buy most of the top hundred companies in America and get some change.

Now keep in mind that none of this was supposed to be possible. In the days when gold facilitated trade, a country would run out of gold before they had a big deficit. In the current period of floating currencies, the assumption, most famously articulated by Milton Friedman while advocating for a transition to such a system in the 1950s, has always been that a country’s currency would adjust to reflect its trade position and to move it back toward balance. So a country that ran large trade deficits for a few years would find less demand for their currency and their currency’s value would drop. This would then make it very difficult for that country to import and easy for it to export in terms of its domestic currency. Therefore, the weak currency would help correct the trade imbalance. Indeed, we see this occurring regularly around the world.

The problem is that this self-correcting mechanism has not applied to the US dollar. We have run trillions of dollars of trade deficits over a relatively brief period of time without our currency weakening substantially. We can debate what the cause of this is. One possible cause is currency manipulation by our trading partners, and surely this is at least among the reasons. Japan weakened its currency to gain competitive advantage. China certainly has. Likewise, other Asian countries have followed the example.

Japan Does Not Run Their Economy Like We Run Ours

The United States has suffered a trade deficit with Japan since 1965. In 2023, that trade deficit was over $71 billion. But as is virtually always the case for the United States, looking at the “balance” masks our dire situation. That’s because our top global exports are oil and gas, while we rely on other countries to actually make things for us. For Japan, our top export is liquified natural gas, while Japan’s top exports to the United States are cars and car parts.

Japan sends us well over a million cars annually, whereas we send Japan about 20,000. Japan’s excess accumulation of U.S. dollars will naturally flow into the acquisition of more U.S. productive assets.

Compounding the tension, Japan rejects foreign investment. According to the U.S. State Department’s 2023 Investment Climate Statement on Japan, Japan’s “inward Foreign Direct Investment stock was 46.6 trillion yen, 8.4 percent of GDP, one of the lowest in the world”.

Secretary Ross omits this reference when he celebrates that “Japan ranks first in foreign direct investment in the U.S., with more than $700 billion in 2022. U.S. firms are the largest foreign investors in Japan.”

The omission by Secretary Ross of any dollar figure on the U.S. investment side only suggests he is perhaps aware of the imbalance.

We do not have to speculate on Ambassador Lighthizer’s position on the Nippon Steel purchase, as he has publicly opposed the takeover:

Over the coming weeks, CPA will highlight important historical moments over the last 75 years when U.S. policy makers failed to see what was plainly happening to our steel industry under our so-called rules based trading system.