President Obama is preparing a major push on a vast free-trade zone that seeks to enlist Republicans as partners and test his premise that Washington can still find common ground on major initiatives.

[Reposted from The Washington Post | David Nakamura | December 26, 2014]

It also will test his willingness to buck his own party in pursuit of a legacy-burnishing achievement. Already, fellow Democrats are accusing him of abandoning past promises on trade and potentially undermining his domestic priority of reducing income inequality.

The dynamic, as the White House plots strategy for the new year when the GOP has full control of Congress, has scrambled traditional political alliances. In recent weeks, Obama has rallied the business community behind his trade agenda, while leading Capitol Hill progressives, including Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), have raised objections and labor and environmental groups have mounted a public relations campaign against it.

The administration is moving aggressively in hopes of wrapping up negotiations by the middle of next year on a 12-nation free-trade pact in the Asia-Pacific region before the politics become even more daunting ahead of the 2016 presidential campaign.

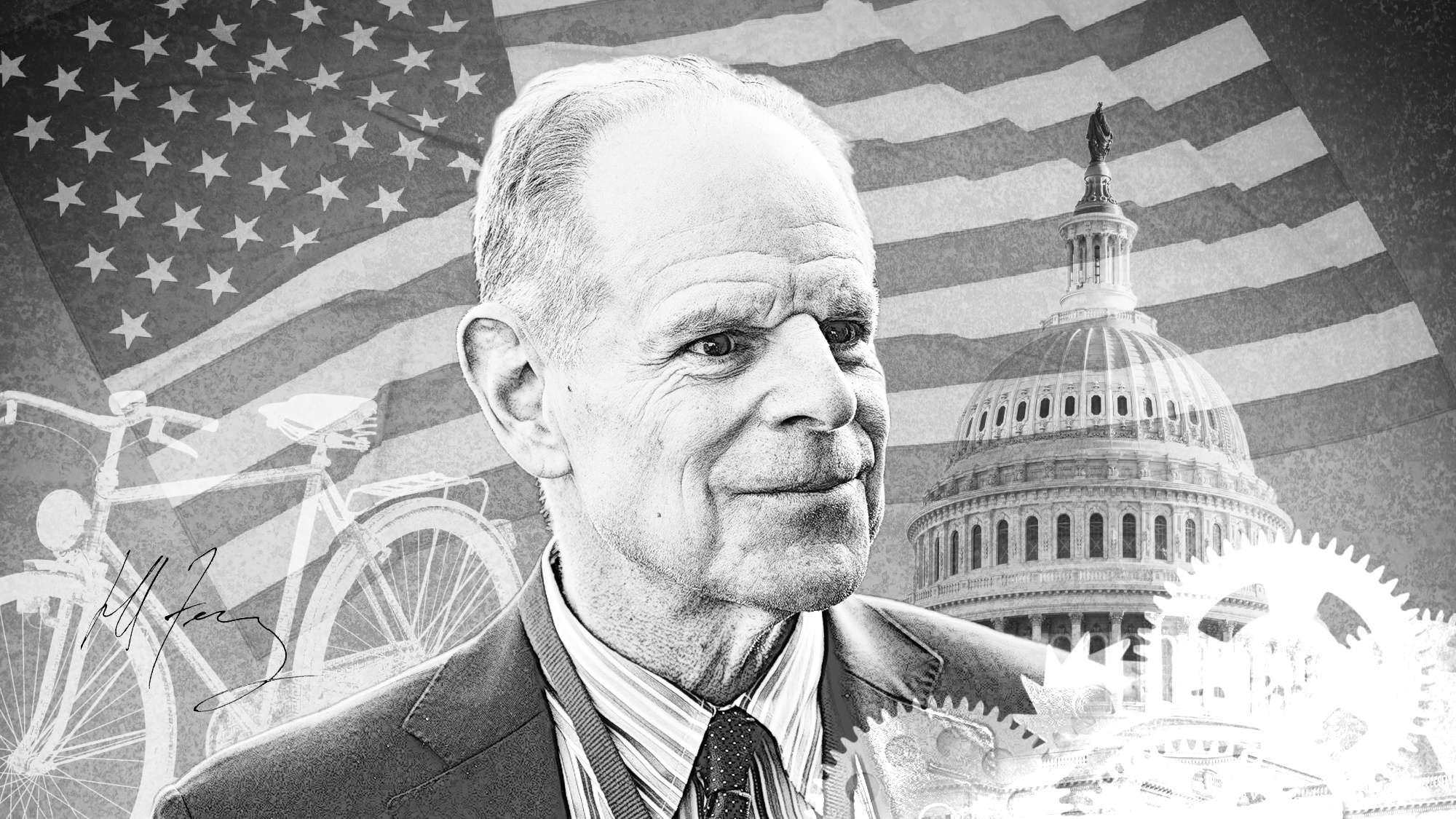

“This is an all-hands-on-deck moment for the administration,” said Rep. Ron Kind (D-Wis.), a pro-trade Democrat viewed by the administration as a key ally. “They need to get out and educate members and address the concerns they might have. I’ve been advising colleagues who are skeptical and not supportive of trade to at least engage in conversations and feedback.”Some states have been threatened much more than other by increased trade.

At issue is Obama’s support for the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), which would establish the world’s largest free-trade zone. The administration has touted the deal as a way to boost U.S. exports to Asia at a time when the United States faces increasing competition from China.

The TPP aims to lower tariffs, establish guidelines on patents and copyrights, and level competition for international companies that compete with government-backed businesses. The first major test could come next month, when Senate Republicans are expected to put forward legislation that would grant U.S. trade negotiators “fast-track authority” to reach final terms that could not be changed by Congress before an up-or-down vote.

Last year, Senate Democrats blocked a White House push for such powers amid pressure from organized labor in an election year. Since the midterms, Obama has ramped up his personal engagement, meeting with the other nations at an international economic summit last month and touting the potential benefits to business leaders in Washington.

Yet Democrats continue to criticize the TPP as little more than a repackaging of previous trade deals, such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), that failed to include enforceable standards on labor conditions and the environment and controls to halt foreign currency manipulation.

In airing their concerns, opponents have reminded Obama of his 2008 campaign, when he spoke skeptically about NAFTA and pledged to renegotiate it once he took office.

“I’m hoping he remembers that campaign and being in Ohio and speaking directly to folks who lost their job because of a trade agreement he was campaigning to renegotiate at that point,” said Rep. Tim Ryan (D-Ohio), who opposes the TPP.

In the past several weeks, Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) held a strategy session with House Democrats about ways to slow the deal; Warren sent a three-page letter to U.S. Trade Representative Michael Froman detailing concerns over provisions she said could undermine financial regulations; and the AFL-CIO launched an anti-TPP advertising campaign in Metro stations in the Washington area.

In response, the Obama administration has launched a “whole of government” campaign to build support in both parties on Capitol Hill. In addition to Froman, Treasury Secretary Jack Lew, Commerce Secretary Penny Pritzker and Labor Secretary Thomas Perez have been involved in discussions with lawmakers.

In a recent address to the Business Roundtable, Obama acknowledged an uphill battle to convince his base that liberalizing trade policy and increasing global competition would not exacerbate wage stagnation after a long period of financial unease among middle-class Americans.

“There’s no doubt that some manufacturing moved offshore in the wake of China entering the [World Trade Organization] and as a consequence of NAFTA,” Obama said. “Now, more of those jobs were lost because of automation and capital investment, but there’s a narrative there that makes for some tough politics.”

The roots of the TPP stretch back to the George W. Bush administration, which first engaged in talks with a far smaller group of Pacific nations. When Obama took office, he put the effort on hold while his administration, in consultation with outside experts, examined trade issues.

That review ran into institutional pushback from bureaucrats and outside pressure from interest groups that made significant reforms difficult, said Kevin P. Gallagher, an associate professor at Boston University who consulted on the project.

He said Obama “was left with, ‘If you can’t reform anything, then you have to be anti-new free-trade agreements.’ But he never said that. He said you need to expand trade because we’re living in a globalized world and we’re all benefiting from it.”

Philip Levy, who consulted for Republican Sen. John McCain’s 2008 presidential campaign, said Obama walked a tricky line as he tried to appeal to both pro-trade Democrats and labor unions.

“The problem is when he gets in office and each side says, ‘Okay, go ahead and deliver,’ ” said Levy, a senior fellow at the Chicago Council on Global Affairs. “It was a completely treacherous, explosive issue, and with almost every move, you’re going to make someone disappointed. They were extremely tentative going in.”

In late 2009, Obama made his first trip to Asia and announced his administration’s intent to resume exploratory talks on the TPP. But it was not until November 2011, at an economic summit in Honolulu, that the president threw his full support behind the pact as part of a broader effort to rebalance U.S. foreign policy to the fast-growing Asia-Pacific region.

That helped persuade other nations, including Japan, which has the world’s third-largest economy, to join the negotiations. The administration has since completed several smaller trade deals, including one with South Korea, that sought to provide momentum.

White House aides said the president views the TPP as making good on his pledge to renegotiate NAFTA because Canada and Mexico are also at the table and because there are sections devoted to higher labor and environmental standards. The administration has warned that China will set the economic ground rules in Asia if the United States does not take the lead.

“I don’t know how it’s good for labor for us to tank a deal that would require Vietnam to improve its laws around labor organization and safety,” Obama told the business leaders.