HONG KONG — As China contends with an economic slowdown and a stock market slump, the authorities on Tuesday sharply devalued the country’s currency, the renminbi, a move that could raise geopolitical tensions and weigh on growth elsewhere.

[Reposted from The New York Times | Neil Gough and Keith Bradsher | August 10, 2015]

The central bank set the official value of the renminbi nearly 2 percent weaker against the dollar. The devaluation is the largest since China’s modern exchange-rate system was introduced at the start of 1994.

China’s abrupt devaluation is the clearest sign yet of mounting concern in Beijing that the country could fall short of its goal of roughly 7 percent economic growth this year. Growth is faltering despite heavy pressure on state-owned banks to lend money readily to companies willing to invest in new factories and equipment, and despite a stepped-up tempo of government spending on high-speed rail lines and other infrastructure projects.

A steep drop in the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock markets in late June and early July, only halted by aggressive government actions, appears to have dented consumer demand within China. Automakers, typically a bellwether of demand, have announced declines in sales last month; Ford China, for example, said last Friday that its sales had fallen 6 percent last month compared with July of last year.

China’s devaluation represents a difficult dilemma for the Obama administration. The United States Treasury has tried to use quiet diplomacy in recent years to encourage China to free up its currency policies, while blocking efforts in Congress to punish China for major intervention in currency markets over the past decade to slow the rise of the renminbi. Many in Congress have long accused China of unfairly building up its manufacturing sector at the expense of American jobs by undervaluing the renminbi, and the Chinese devaluation could fan those criticisms.

In a seeming nod to such concerns, the central bank said that it would begin to use the market closing, not the previous morning’s official setting, to calculate the renminbi’s official daily fixing against the dollar. But China’s economic weakness now means that further opening up of the currency to market forces could mean a weaker renminbi, not a stronger one. That, in turn, would make Chinese goods even more competitive in the United States and Europe.

China’s central bank “has finally thrown in the towel on supporting the renminbi,” said Eswar S. Prasad, a professor of economics at Cornell University. At the same time, he added, easing its grip on the currency’s value “has blunted criticism by combining the currency devaluation with a more market-determined exchange rate.” The United States and institutions such as the International Monetary Fund have called on China to be more hands-off in managing the renminbi.

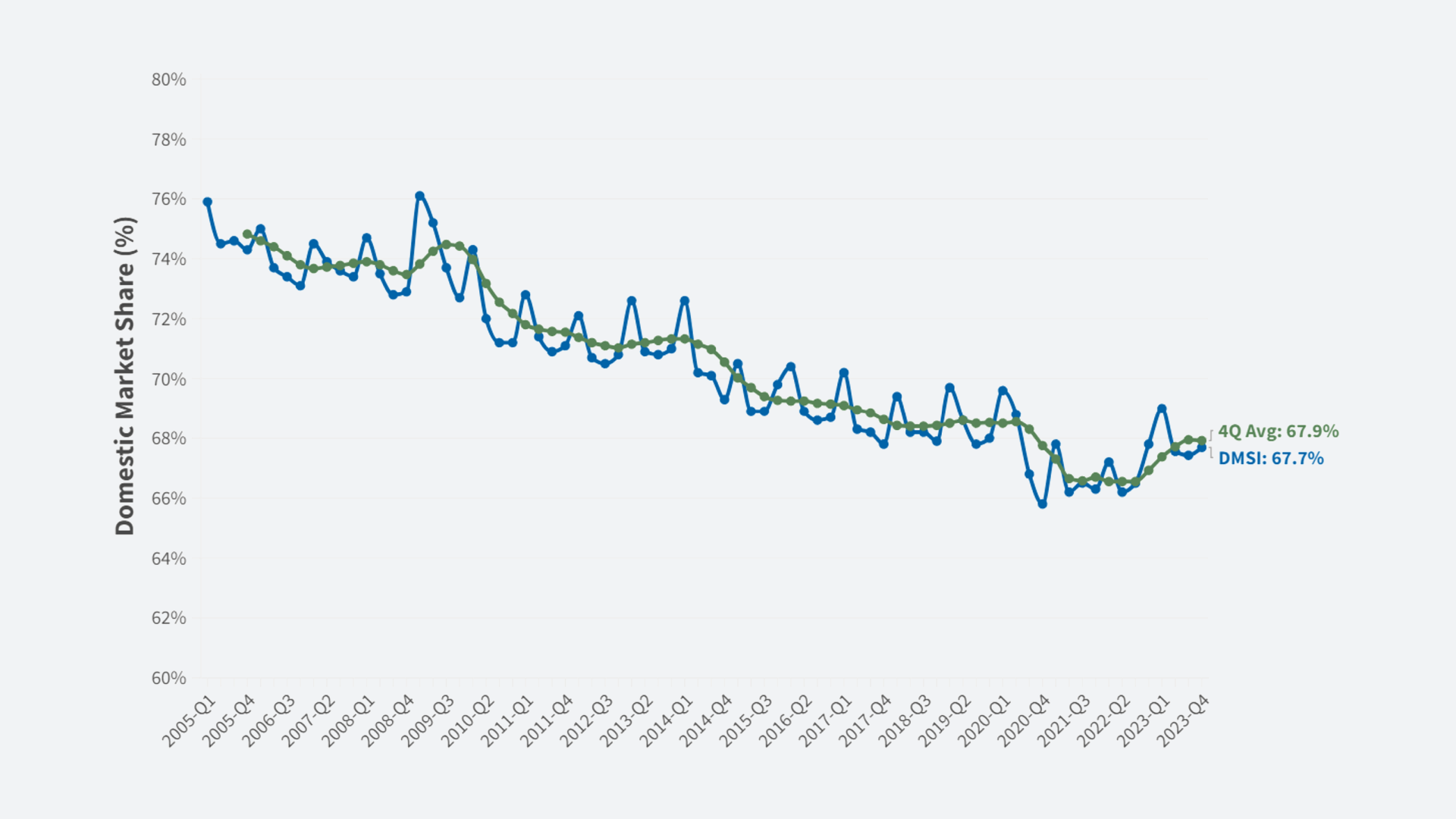

The Chinese currency has been a global point of contention for nearly a decade. China officially ended the renminbi’s fixed peg to the dollar in 2005. Since then, it has risen in two long, slow climbs. The first was from July 2005 to August 2008, when it was interrupted by the global financial crisis. The renminbi then resumed its rise from June 2010 to early last year, when it dipped slightly, then stabilized.

The overall increase since 2005 has been more than 25 percent against the dollar. It has strengthened even more against other major currencies, like the euro and the yen.

But the Chinese currency is not freely tradable, and its movements are tightly controlled by the government.

Each morning in Shanghai, China’s central bank sets a midpoint for the renminbi’s value against the dollar and other major currencies. This can be as much as 2 percent higher or lower than the previous day’s value, although the change is almost always a tiny fraction of 1 percent.

But on Tuesday, the central bank fixed the value of the renminbi at 6.2298 per dollar, down 1.9 percent from Monday’s official fixing. In a statement on its website, the central bank said it was seeking “to perfect” the renminbi’s exchange rate against the dollar.

The bank, the People’s Bank of China, said it was reacting to trends in the market, where traders in recent months had been betting on a weaker renminbi. In trading in mainland China on Tuesday, the renminbi weakened further to close at 6.3231 per dollar, a drop of 1.8 percent from the close on Monday. By the end of the Asian business day, it had fallen even further in offshore trading to around 6.36 renminbi per dollar, a drop of about 2.7 percent, signaling overseas investors expected further weakening.

Changing Value

The Chinese authorities on Tuesday sharply devalued the country’s currency, the renminbi, relative to the dollar.

The move also jolted the currencies of countries that depend heavily on China as a market for exports. The Australian dollar fell 1.1 percent against the United States dollar on Tuesday, and the South Korean won declined 1.4 percent.

“While China’s policy makers have long suggested that foreign exchange reforms would happen, the abrupt nature of today’s announcement has injected considerable volatility into the renminbi and other Asian currencies,” analysts at HSBC wrote Tuesday in a research note.

The central bank also said it would seek to prevent what it described as “abnormal” capital flows. Weaker economic growth has prompted sizable outflows from China in recent months, which have most likely been exacerbated by the country’s stock market volatility. A falling renminbi generally increases the risk of more outflows.

While China grew at a 7 percent rate in the first half of the year, that was made possible mainly because of a boost from the financial services industry, which benefited from the country’s stock market boom. With the downturn in the nation’s markets over the past two months, growth is slowing more evidently.

This is despite an all-out effort by the government to prop up share prices. The measures included extraordinary support from state-run banks, which in July made new loans worth 1.5 trillion renminbi, or about $240 billion at the time, according to data released Tuesday. The last time Chinese banks approached that amount of lending was 2009, when Beijing was deploying 4 trillion renminbi in stimulus to stem the damage from the global financial crisis.

A depreciating renminbi also has implications for China’s pledges to open its economy and financial markets wider, including efforts in recent years to lift the currency’s global prominence.

The central bank has been lobbying the International Monetary Fund to include the renminbi among freely traded benchmarks like the dollar, euro and yen, so that other countries can include it as an official reserve currency.

While acknowledging these efforts, the fund issued a report last week saying that “significant work remains outstanding” before it could decide whether to include the renminbi as a global benchmark, adding that no changes were likely to be made before September of next year.

The fund also singled out China’s official daily fixing of the renminbi’s exchange rate, saying this “is not based on actual market trades.”

Tuesday’s devaluation “is likely intended to improve the ‘market-driven’ quality” of the exchange rate to appeal to the I.M.F., Wang Tao, the chief China economist at UBS, wrote Tuesday in a research note.

“However, we think it unlikely that the Chinese government will let only market momentum drive the renminbi exchange rate from now on,” Ms. Wang added, “as that can be quite destabilizing.”