The “Green Revolution” promises to produce electric power in a climate-friendly, low-emissions manner for homes, businesses, cars, trucks and other vehicles. There’s just one giant stumbling block. All these clean-energy sources use large amounts of copper. Global copper demand is forecast to double between now and 2035. But copper supply may not keep up. If that happens, it throws doubt over the ability of many companies—both U.S. and international—to follow through on their current plans. And the U.S. is badly positioned compared to many competitors—especially China—when it comes to accessing copper supplies.

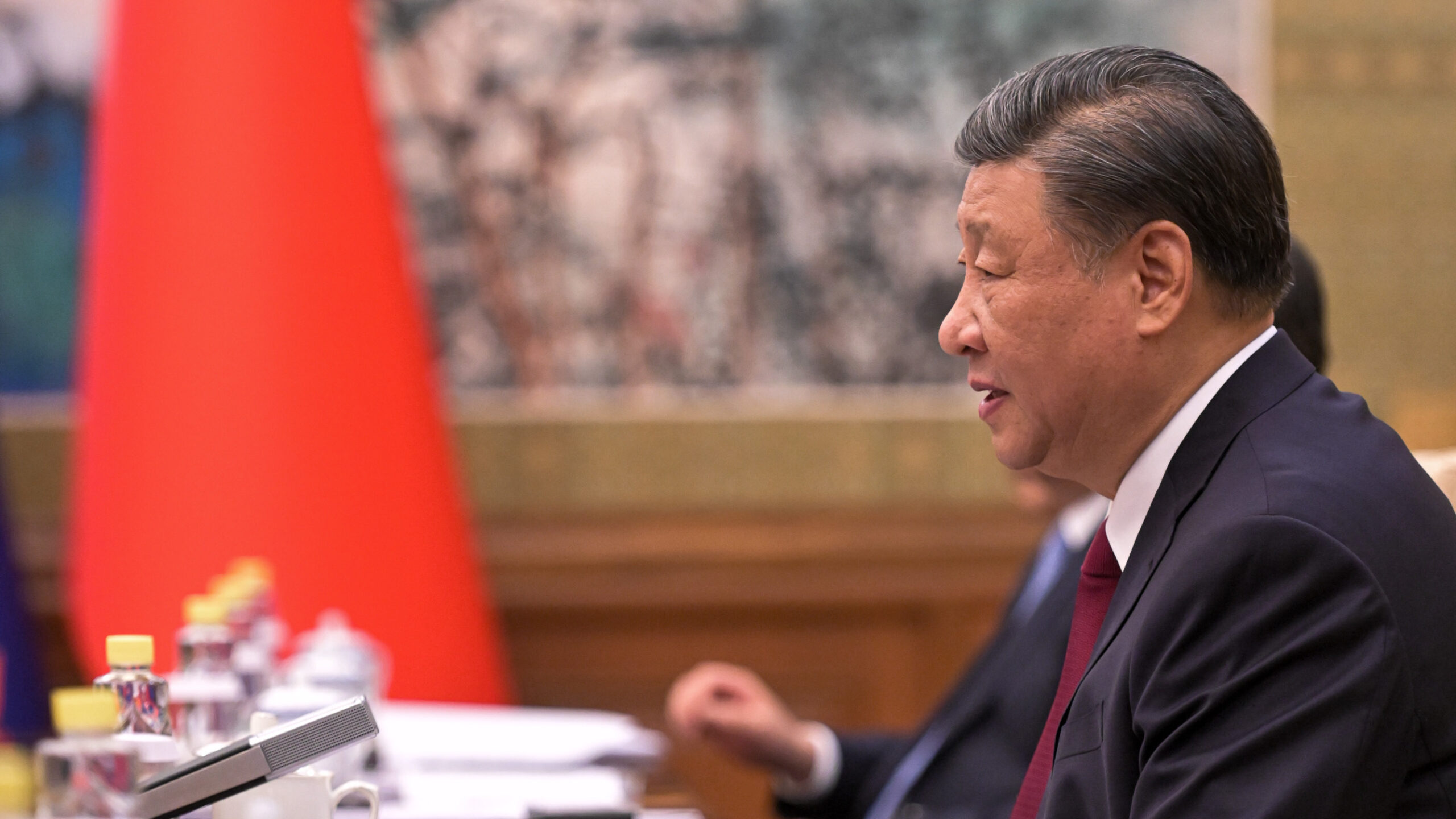

In an in-depth report published last summer by S&P Global, copper analysts forecast a shortage of as much as 10 million tons by 2035. “There will be a new geopolitical order around minerals like copper,” S&P vice-chairman Daniel Yergin told CNBC[1]. “China has been more focused on creating a primary position in the supply chains for minerals that will be necessary for net-zero carbon, and copper is a prime example for what a key position they’re in. Meanwhile, U.S. copper production has gone down by almost half in the last quarter century,” he told CNBC.

The transition to electric vehicles (EVs) provides a good illustration of how dependent green energy technologies are on copper. According to S&P Global, the typical internal combustion engine vehicle uses 24 kilograms (53 lbs) of copper. A battery-powered EV uses 60 kg (132 lbs) of copper for a light-duty EV. A medium-duty EV requires 139 kg (306 lbs) of copper, while a heavy-duty, battery-powered EV uses 425 kg (935 lbs) of copper. [2]

Last year, the U.S. consumed 2 million tons of copper. According to data from the U.S. Geological Survey, about 45% of that total was imported. Around 60% was mined from copper mines. About 210,000 tons, or 10%, was recovered from scrap. (Some 400,000 tons were exported, which is why the figures for copper production exceed 100% of consumption.)

Prospects for increasing the amount of copper that can be mined are not encouraging. Mined production in 2021 was down 5% compared with 2019. According to industry analysts, mining companies have avoided investing large sums in new mines since the 2008 recession left many of them with large debt burdens. In the U.S., it is especially hard to build a profitable copper mine since it takes an average of seven to 10 years from the application for mining permits to a mine finally commencing operations. While the Biden administration has put tax credits for critical minerals into the new Inflation Reduction Act, it has yet to take any action to simplify or speed up the mine permitting process—which involves approvals from multiple agencies at the federal, state, and local levels.

This leaves scrap as a more likely source of rising copper supply. Scrap supplied to the U.S. market rose 13% between 2017 and 2021. In a 2022 report, S&P Global said recycling of copper scrap into copper could be increased through technological development, capital investment in recycling equipment, and government support, since recycling produces less emissions than the mining of virgin copper. According to S&P Global, “copper scrap supply boasts the potential to be a major disruptor to primary copper supply, and a force to satisfy the expected growth in copper demand from the renewable energy transition and electric vehicle revolution.”[3]

According to USGS data, the U.S. is the fifth largest miner of copper in the world. But in terms of refined copper production, the U.S. refines only 1 million tons a year. China is the world leader in production of refined copper, with 10 times the output of the U.S. China’s huge output is the result of years of government support for the industry. The Communist government has long viewed copper as an enabling technology for production of other electronic products in China’s five-year plans.

If copper supply fails to keep up with demand, either within the U.S. or globally, the inevitable result is a rise in the copper price. Copper, like other commodity metals, has a highly volatile price. Copper analysts Goehring and Rozencwag, see realistic prospects of a large jump in the world copper price. In a 2021 report, they wrote:

“The previous copper bull market took place between 2001 and 2011 and saw prices rise seven-fold: from $0.60 to $4.62 per pound…. The fundamentals today are even more bullish. We would not be surprised to see copper prices again advance a minimum of seven-fold before this bull market is over. Using $1.95 as our starting point, we expect copper prices to potentially peak near $15 per pound by the latter part of this decade.”[4]

The 132 lbs of copper in an EV costs roughly $660 at today’s price (of $5 per pound). If copper were to rise to $15 per pound, that cost would rise to nearly $2,000. With its huge refining capacity, government support, and good relations with copper-producing nations like the Congo, China will have the capability to hold its copper costs in check. This would be a serious handicap for U.S. dreams of building a large EV industry. And today, outside of Tesla, which sold 936,000 EVs last year, they are still just dreams.

[1] CNBC, Copper Shortage Could Derail Energy Transition, Report Finds, July 14, 2022. Available here.

[2] Camellia Moors, Kip Keen, Looming copper shortage shifts attention to alternative supply solutions, Sept. 7, 2022. Available here

[3] Aline Soares, Copper scrap boasts decarbonization benefits amid challenging market dynamics, March 3, 2002. Available here.

[4] Goehring and Rozencwajg, The Problems with Copper Supply, Q1 2021. Available here.