Editors note: Any candidate who will not fully repudiate any TPP-like agreement is hiding his/her views, will be “for” those economically destructive agreements and therefore should not be in the oval office.

The Atlantic surveyed the Democratic presidential candidates on whether they support the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Only some took a definitive position.

[Edward-Isaac Dovere, Madeleine Carlisle and Olivia Paschal | June 26, 2019 | The Atlantic]

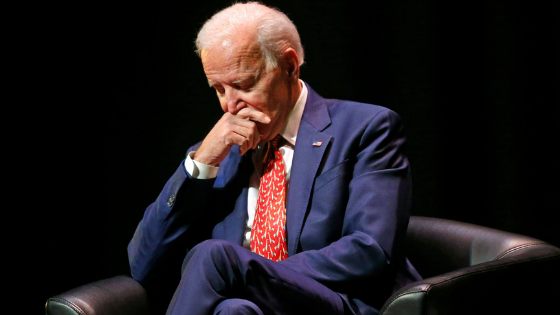

Toward the end of his vice presidency, Joe Biden was a prime player in the administration’s bid to win support for the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the failed trade deal that was supposed to be the crowning achievement of Barack Obama’s presidency-long “pivot to Asia.” Biden liked to hold up two maps of the Pacific region—one shaded in blue to show America’s influence in the region if the deal passed, and one shaded in red to show China’s growing influence if it didn’t.

“I think it’s very, very important to understand that the 20th-century rules of the road no longer exist, and new ones have to be written, and we should write them,” I heard him say in April 2015, to a gathering of the insistently moderate New Democrat Coalition at a hotel on the Chesapeake Bay. To other crowds, Biden and others in the administration would try to sell it as Obama’s trade deal, arguing that people should support it because they liked and trusted the president.

On the eve of the first presidential-primary debates, however, Biden’s 2020 campaign wouldn’t say whether he still supported the deal. He’s far from alone—Democratic candidates are quick to say they’d immediately rejoin the Iran nuclear deal and the Paris climate agreement, both of which Obama helped put in place, but his TPP remains toxic. Even as Biden is running explicitly as a restoration of the Obama presidency, his campaign press secretary declined to comment on what his position is, other than to point to recent remarks the former vice president has made: that he opposes President Donald Trump’s trade war, and that he’d like higher labor standards in the revamped NAFTA agreement that the current administration is hoping to get approved by Congress. The campaign says more details on what he’d do on trade will be coming soon.

That seems to reflect the Democratic Party’s current crisis on trade, with even most of the people running for the presidential nomination unable to articulate a clear vision of what America’s approach should be. The Atlantic asked 23 Democratic presidential candidates whether they support TPP and would want to restart negotiations if elected, and received only some definitive responses. Of the people who were firm in their answers, former Representative John Delaney of Maryland is the only one who said yes.

Several candidates’ campaigns didn’t provide answers on their current position on TPP despite repeated requests: South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg; Senator Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota; and Representative Tulsi Gabbard of Hawaii.

Of the definitive responses, Julián Castro, who was in Obama’s Cabinet during the TPP push, said that although he sees the value of “vigorous trade,” he wouldn’t support the deal as originally negotiated. Was Obama wrong to have pushed for it? “No,” said the former secretary of housing and urban development. “That’s what the administration believed was an improvement. That trade agreement was an improvement over NAFTA in its labor provisions, its environmental provisions—but we’re going to keep getting stronger. We’re not going to settle for the standards of the past.”

Delaney explained his outlier “yes” in terms of a “Trump vision of the world versus the Obama vision of the world.” The former president “became really good at understanding the U.S. role globally and how you tie economic relations to global relations to economic security,” Delaney said. “I don’t think you can actually take on Trump unless you are for the TPP, because I don’t think you can actually say, ‘Your vision of the world is wrong if you basically opposed Obama’s vision of the world.’ I actually thought we lost the election over it last time.”

Trade was one of the most divisive, definitive issues in the 2016 Democratic-primary campaign—and in the general election. Both Trump and Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont tapped into decades of simmering rage over gutted manufacturing towns, declaring their opposition to trade agreements such as NAFTA and TPP that they say are bad for the American worker. In the early days of the Democratic primary, when Biden was still rumored to jump into the race, Hillary Clinton was spooked enough to announce her opposition to TPP. She wanted to box him out and protect her support from unions—even though she’d helped lead the early negotiations for the deal. The anti-trade edges of the Democratic and Republican bases converged, and America seemed to be moving firmly away from its traditional leadership on global trade.

Trade opponents tended to have the loudest voices in 2016, and they were concentrated in states that have become the hottest battlegrounds for general elections, including Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. But they didn’t—and they don’t—represent the full picture of where Americans are on trade. For example, in public polls, younger voters are consistently much more open to global trade. And the debate over TPP was often framed in simplistic terms, eliding the details of an agreement that involved 12 countries, in which all agreed to a baseline of standards about workers’ rights and proper working conditions—a baseline seen, among opponents on the left, as settling for the lowest common denominator.

Supporters pointed to the economic opportunities of further opening markets for American goods, but critics argued that the agreement would result in domestic jobs being moved overseas. Trump often says he pulled out of the TPP. But the United States never actually formally made it into the agreement: The deal had been waiting for months for a vote in Congress when Trump withdrew the United States, almost immediately after his inauguration. Since then, China has kept moving forward. And other countries party to TPP have made their own agreement, while suggesting that they’d be open to America coming back in should there be a change of heart—or administration.

Don’t expect that to come with Sanders in the White House. “He would only support trade agreements that were fair to American workers and were written through an engaged, democratic process,” said his campaign press secretary, Briahna Gray. Same goes for an Elizabeth Warren administration: The senator from Massachusetts “thought the deal had weak labor standards, toothless enforcement provisions, and special private courts for multinational corporations,” said Saloni Sharma, a spokeswoman for Warren.

Though TPP itself never came up for a vote on Capitol Hill, in 2015 a related bill called Trade Promotion Authority did. It allowed Congress to take a simple initial yes/no vote on approving trade deals, rather than having each section of an agreement subject to debate. In practice, voting for TPA was largely seen as a vote for TPP, because it was passed with the understanding that Obama would immediately use it to send his trade deal up for a final vote.

Neither Warren nor Sanders voted for TPA. But several other 2020 hopefuls approved the measure—creating some noteworthy juxtapositions with their positions now.

Take Senator Michael Bennet of Colorado. His spokesperson noted that Bennet wanted TPP to better address “the very real economic pain that American families are feeling from globalization and the changing economy.” But “he also doesn’t think we should cede to China writing the rules for trade in the Asia-Pacific region, as President Trump has done.”

Or take former Representative Beto O’Rourke of Texas, who also voted for TPA. Asked where the candidate stands on TPP, O’Rourke’s communications director, Chris Evans, went after Trump: “This president’s go-it-alone and shoot-from-the-hip trade policy is jeopardizing the very livelihood of American farmers and workers while imposing a tax hike on American consumers,” Evans said. “As president, Beto would only support trade agreements that put American workers, farmers, and consumers at the center. He will also ensure that all U.S. trade agreements have strong worker and environmental protections with strong enforcement mechanisms.”

Some of the 2020 candidates who opposed TPA similarly parsed the issue, saying they’d support TPP if TPP were improved. Representative Tim Ryan of Ohio, who aims to be the voice of the often overlooked industrial Midwest in the campaign, believes the United States needs to “make inroads” with Pacific countries to counter China, said his campaign spokesman, Michael Zetts. But while Ryan “was a vocal opponent” of TPP, he “would look at rejoining the agreement if we could secure increased labor standards, stronger environmental protections, and better human-rights protections.”

Representative Seth Moulton of Massachusetts, who also voted against TPA, said he wants a deal with higher standards than TPP. But “by simply abandoning TPP with no alternative—which is what a lot of people are talking about doing and certainly what Trump has done—means that China sets the rules of the road,” he said at a campaign-stop interview in South Carolina last weekend. “And that is wrong.” Representative Eric Swalwell of California, another TPA opponent, was also short on specifics about what to do next. “Let’s get a better deal,” he said in a statement provided over email. “I’m open to any trade deal that means more good-paying jobs for U.S. workers.”

Similarly seeking to improve TPP is former Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper. A spokesperson said he’d want to renegotiate the agreement to give “trade-impacted workers and areas” extra help. “He recognizes the value of global engagement and our partnerships with our Pacific trade partners,” the spokesperson said. “But he would seek to negotiate a TPP that includes stronger provisions for workers and the environment.”

Warren and Sanders aren’t the only senators opposed to TPP. Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey stands by his opposition to TPA and TPP, said his press secretary, Sabrina Singh. “It put large corporations before workers and would have led to the decline of U.S. manufacturing,” Singh said. According to a spokesperson, Senator Kirsten Gillibrand of New York, who also voted against TPA and opposed TPP, “believes U.S. participation in any trade agreement needs to have a real strategy behind it.” It “must hold bad actors accountable, promote fair trade, protect American workers and the environment, and deliver real economic growth to middle-class families,” the spokesperson explained.

Other candidates weren’t in Congress for the TPA vote, and some may not have taken a position on TPP until now. Senator Kamala Harris of California opposed TPP when she campaigned for the Senate in 2016, “pointing to its lack of worker protections,” said her press secretary, Ian Sams, adding that she wouldn’t join the agreement as president. In an interview last week in South Carolina, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio said, “TPP was a huge mistake, and it was a giveaway to corporations, and we need an entirely different approach to fair trade.” What does that mean? “Total emphasis on standards for working people in all the affected countries—wage and benefits standards, labor conditions, strong environmental standards.” And it “especially has to not be something that explicitly empowers corporations over governments that are supposed to have the back of the people,” de Blasio added.

Jay Inslee, the Washington State governor, didn’t take a position on TPP when Obama was negotiating the agreement, but he said his future support for the deal would hinge on his signature focus: climate. In an interview in Iowa recently, he argued in favor of putting carbon-emissions trading into any future agreement. When asked whether he is open to international trade, he noted that more than a quarter of the jobs in his state are based on trade. “I start with the proposition that trade can be mutually beneficial,” said Inslee, who voted for the original NAFTA in 1993, when he was newly elected to Congress. But “there are people who lose in trade … We’ve got to have a much more robust transition plan for communities involved in that.”

Montana Governor Steve Bullock, who also hadn’t previously taken a stand on TPP, now opposes how it was written, though a campaign spokesperson noted that he believes Trump’s withdrawal has resulted in America “on the sidelines,” as the countries previously party to TPP increase trade among themselves and with China too. As president, Bullock “would carefully assess all trade agreements, fight for U.S. workers and environmental interests, and ensure any agreement is accompanied by meaningful worker retraining at home for impacted industries,” the spokesperson said.

The self-help author Marianne Williamson was one of the few firm no’s on TPP. Andrew Yang was a firm sort-of. “If we do TPP and all the money’s going to go to the top, he won’t support it,” said his press secretary, Randy Jones. “If there’s a mechanism in there that lets average Americans get the benefits, he’d support it.”

Yang’s response perhaps best captures just how confused the Democratic Party is on trade right now: A candidate with no record in office, running a campaign with little to lose, still apparently finds TPP too tricky an issue to have a clear position on. On that front, he has company—including the race’s front-runner.

Read the original article here.