KEY POINTS:

- Rebuilding U.S. manufacturing is gaining support in both political parties and both presidential candidates.

- Republicans favor tariffs; Democrats favor tax credits. Both aim for the same goal.

- “Productivism” is a new economic concept endorsing support for key industries essential to economic growth and national security.

- The Rubio-Khanna National Development Act lays out an exciting path forward for industrial policies.

The pro-American economic policies of President Biden and President Trump before him have been under sustained attack in financial press in recent weeks. The Wall Street Journal is waging a sustained campaign against industrial policies. Onetime trade ambassador Robert Zoellick emerged from his crypt to tell us that what we have today is the “Biden-Trump Economy of Nostalgia.” Economist Michael Strain summed up the anger of mainstream, neoliberal economists in the Financial Times, claiming “Protectionism is Running Amok in the US.”

All these attacks make the mistake of believing that free trade leads to economic growth. For the United States this is dead wrong. Economists, politicians, and their followers in the mainstream press confuse two different theoretical approaches to economics. The economic theory of free trade, first developed by David Ricardo in 1817, focuses on a nation’s opportunity to maximize output at the present moment, given its present set of capabilities, resources, and skills, and the capabilities of other nations. It is a short-term theory. It also assumes full employment.

However, long-term economic growth is an entirely different issue. A nation’s long-term growth depends on many things, including the skills and education of its people, its natural resources, the rule of law, and a government sensible enough to refrain from meddling in the private sector, or if it meddles, to do so intelligently. Most of all, prosperity depends on a nation investing in the right industries that can propel growth forward over a period of decades.

In a choice between short-term output maximization and long-term growth, long-term growth is clearly the more important goal. Long-term growth can transform a nation in a single generation. Short-term output maximization often leads to static, inflexible, volatile economies, dominated by one industry. That industry often pays its workers badly due to its dominant position, leading to high levels of inequality. Think of Greece, whose economy is dominated by its “comparative advantage” in tourism, or the Congo, dominated by mining. While the beaches of Greece are very attractive, when you have hundreds of hotels all offering similar experiences, competition leads to very low wages for staff and a stagnant economy. And when an unexpected shock disrupts the one dominant industry, the whole economy crashes. This is exactly what happened when COVID hit tourism-dependent economies such as Greece especially hard.

David Ricardo himself recognized the static nature of his comparative advantage concept. However, he believed it played into the advantages of Great Britain, which was then the world’s manufacturing leader. In his classic work, Principles of Political Economy, Ricardo wrote: “It is this principle which determines that wine shall be made in France and Portugal, that corn shall be grown in America and Poland, and that hardware and other goods shall be manufactured in England.”[1]

On the comparative advantage principle, America would have remained a nation focused on agriculture for decades after 1817. Fortunately for us, the hostile actions of Britain and France during the Napoleonic wars led Presidents Jefferson and Madison to impose an embargo, followed by tariffs, in order to block British imports and stimulate U.S. development of industry to equip an army and navy with arms and ships to defend itself. This blatant rejection of comparative advantage launched the U.S. into industrialization which made us the world’s richest nation and a superpower.[2]

Fast-forward to the 1990s when the U.S. led the world into what is now known as hyper-globalization, an accelerated process of promoting trade and offshoring. Comparative advantage theory does not envisage a situation where different nations have differing levels of costs. For high-wage, high-cost nations like the U.S., global competition in high-value industries forced the U.S. to make a terrible choice: either cut costs to levels competitive with low-wage nations, or let industry decline and disappear, i.e. deindustrialization. With competitor nations’ wages some 80%-90% below U.S. levels, the U.S. chose deindustrialization.

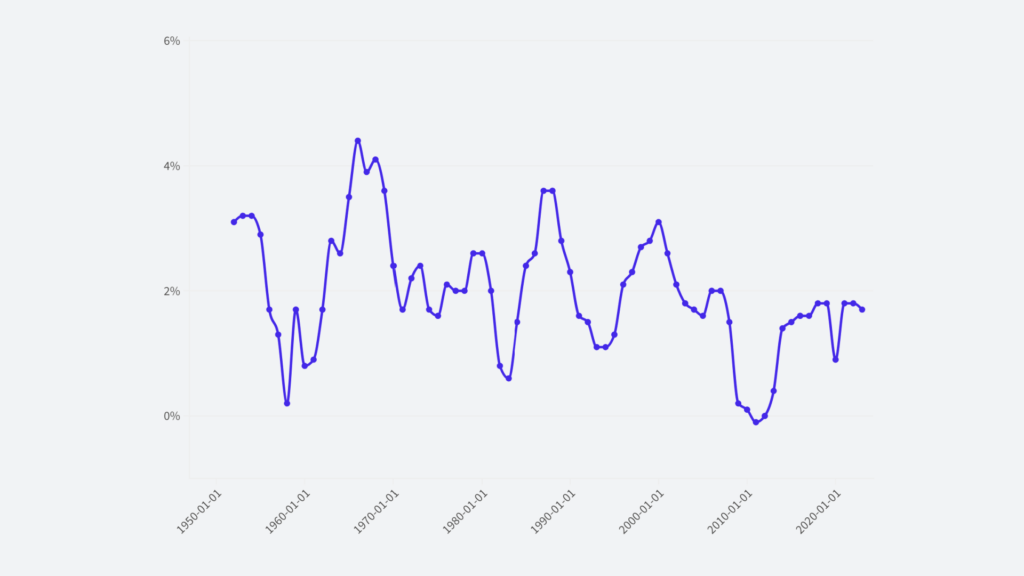

Figure 1 shows the decline in U.S. productivity growth since 1988. Between 1950 and 1988, U.S. productivity growth per person averaged around 3% to 4% a year. That was the period when working class families readily ascended to the middle class, and millions of workers were able to buy a home, run two cars, and accumulate material possessions their parents never had. But in the 1980s, productivity began to fall. There was a short-lived mini-boom in the late 1990s. Since 2000, annual productivity growth has struggled to reach 2%.

Figure 1. The post-2000 slowdown in US productivity growth

The 2016 election of Donald Trump as president marked a sea-change in the way the political class thought about the U.S. economy. Since then, both the Trump and Biden administrations have sought to rebuild U.S. manufacturing industries through tariffs, tax credits, and other policies.

Such pro-manufacturing policies have been christened “productivism” by Harvard Kennedy School economist Dani Rodrik. These policies emphasize the importance of promoting the productive capabilities of an economy. Rodrik (like myself) is Keynesian in the sense that he believes that demand can be managed to minimize the impact of recessions. He also recognizes that Milton Friedman’s monetarist and free-market paradigm (rechristened “neoliberalism” or the Washington Consensus) has its value. But neither of those economic paradigms can address the supply-side challenge of a nation losing its most productive industries due to low-wage foreign competition. Supply-side as used by Rodrik and myself does not refer to tax cuts but to direct action to boost the most productive industries. Here’s Rodrik’s summary:

“[Productivism] is an approach that prioritizes the dissemination of productive economic opportunities throughout all regions of the economy and segments of the labor force. It differs from what immediately preceded it (“neoliberalism”) in that it gives governments (and civil society) a significant role in achieving that goal. It puts less faith in markets and is suspicious of large corporations. It emphasizes production and investment over finance, and revitalizing local communities over globalization. It also departs from the Keynesian welfare state – the paradigm that “neoliberalism” replaced — in that it focuses less on redistribution, social transfers, and macroeconomic management and more on creating economic opportunity by working on the supply side of the economy to create good, productive jobs for everyone. And productivism diverges from both of its antecedents by exhibiting greater skepticism towards technocrats and being less instinctively hostile to populism in the economic sphere.”[3]

Trump's Tariffs

In 2018 and 2019, President Trump implemented tariffs on several industries and a broad set of tariffs on roughly half of U.S. imports from China.

The most successful of these tariffs from the economic point of view were the global tariffs. The steel tariffs led U.S. steel companies to invest in some 15 new steel facilities including steelmaking and steel mills, all over the U.S. Those new facilities have taken on thousands of new employees, mostly in “heartland” America, the very places where the local economies were blindsided by the surge in imports from China and other low-wage nations in the years after 2000. The solar equipment tariffs led solar energy manufacturers to invest in new solar module facilities, kicking off the rebirth of an industry that had come close to death under the onslaught of subsidized Chinese solar panels that began around 2010.

Much of the criticism of tariffs involves the claim that tariffs have raised prices. Yet actual price data does not bear this out. Increases in the consumer price index were low in 2018 and 2019. The CPI increase in 2019, at 1.8%, is a figure the Federal Reserve can only dream about today. By contrast, prices shot up in the post-Covid inflation beginning in late 2021. The 2021-2024 surge in prices, around 25% as measured by the CPI index, was due to the combination of supply chain snafus (due to heavy reliance on imports in many industries) and excessive fiscal/monetary spending.

Prices of industrial or consumer goods are affected by many factors, not just the cost of a tariff. Competition and changes in supply and demand are the most important factors in setting prices. What we have seen after the Trump tariffs is that in most markets, where there is significant domestic competition, tariffs have only a minimal impact on prices. The International Trade Commission estimated the price impact of a tariff at between 10% and 20% of the tariff value (in other words, a 25% tariff leads to only a 2.5% increase in prices in the U.S. market). Studies by academic economists have noted that the impact of tariffs on retail prices was “not easily visible”[4] in retail price indexes—in other words, there was no correlation between tariffs and retail price changes.

A typical example of economists’ misleading tariff-prices argument comes in a paper by Sherman Robinson of the Peterson Institute, claiming that tariffs on steel, aluminum, and lumber add 1.3 percentage points to the consumer price index. The paper is based entirely on what Robinson calls a “trade-focused simulation model” of the world economy. There is no real price data in the model, simply a set of assumptions of how global prices and costs interact. Yet this type of simplified model is quoted by other economists, such as Peter Morici, as if it contained real evidence.

The Trump administration’s global tariffs had a strong positive impact on the sectors where they were applied. The China tariffs served a national security purpose in that they have reduced our dependence on China, or at least began that process. However, the results of the China-focused tariffs in terms of reshoring U.S. manufacturing have been small. Most of the trade and investment diverted away from China went to Southeast Asia, Mexico, India, and elsewhere.

While China has used every trick in the book (subsidies, IP theft, forced labor, huge trade surpluses, artificially low prices, currency manipulation, and more) to exploit and increase its advantages in the world economy, even a country like Mexico, with little that can be called a coherent economic policy, has profited from U.S. deindustrialization. Such is the offshoring power of the low-wage/high-wage differential built into hyper-globalization.

Biden's Tax Credits

President Biden’s tax credit policies, as represented by his three major achievements, the infrastructure bill, the CHIPS Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), aim to achieve similar results to Trump’s tariffs. The three laws have kicked off a huge construction boom, notably in the EV, battery, and semiconductor industries as new plants are built across the country. It is too early to judge if they will be successful, because it is hard to know whether all these investments will be profitable and sustainable.

Some observations can be made. Tax credits tend to be less controversial on the international scene and are therefore less likely to lead to retaliation. And retaliation, even if it comes, in the form of tax credits enacted by our trading partners, is less of a concern because the U.S. market is so large and the credits so generous that manufacturing companies will find it hard to resist investing in America. Most important, the credits have been enacted on a 10-year timescale, which gives corporate investors the certainty that an investment today will earn tax credits for years to come. Tariffs tend to be short-term, subject to legal challenges and political debate, and are often enacted on a declining scale, for reasons understood only by lawyers who have never tried to build a business plan.

Tariffs have the advantage of not favoring individual companies. Biden’s tax credits have clearly been written to target certain companies, such as Intel and General Motors. This opens them up to the charge of favoring special interests. They are also huge bets on specific companies which may or may not make good use of the funds. Still worse, tax credit bills tend to be written, like most congressional bills, in response to lobbying pressure. Large, struggling companies like GM and Intel spend millions of dollars a year on lobbying. Labor unions also have substantial clout in Washington.

In summary, each policy has its advantages and disadvantages. Given the weakened state of U.S. manufacturing, the huge wage differential between the U.S. and low-wage nations, and the aggressive policies of China to force its overproduction on other nations, both tariffs and tax credits need to be used to rebuild the U.S. economy.

As Figure 2 shows, manufacturing production in the U.S. has been broadly flat since January 2016, fluctuating within a narrow range of 98-102 (except for the Covid lockdown period). Broadly speaking, neither the tariff nor tax credit policies have been sufficient to put U.S. manufacturing output on an upward curve.

CPA’s Domestic Market Share Index (DMSI) shows a somewhat worse trend. The DMSI index measures the share of domestic manufacturing demand met by U.S.-based producers. It therefore excludes the effect of business cycles (booms and recessions) and measures specifically how domestic producers are doing compared with their import competitors. Since 2005, the DMSI has fallen by eight points, from 76 to 68. In other words, last year, imports took 32% of the U.S. market for manufactured goods.

Figure 2. The Fed’s index of manufacturing production has been effectively flat since 2016.

Figure 3. U.S-based manufacturing has lost 8 points of share to imports since 2005.

Clearly, not enough is being done to rebuild U.S. manufacturing. A big part of the problem is that out of the spotlight, offshoring is continuing. For example, last month Master Lock closed its century-old manufacturing facility in Milwaukee, laying off the last employees from what had once been a facility that employed over 1,000 workers. Master Lock gave into years of relentless low-price competition from China by shifting production to Mexico.

Even more significant for U.S. manufacturing are trends at General Motors. CEO Mary Barra began her January 30th earnings conference call by praising two new GM models which are proving popular with young consumers. Those models, the Chevrolet Trax and the Buick Envista, are both made in South Korea. She went on to praise the new Chevrolet Equinox, an SUV new for 2025 and made in Mexico. The IRA tax credits will ensure that most new EVs are made in the USA, but until they reach significant volume, Barra explained that GM will offset the $1.3 billion of additional labor costs due to last year’s UAW settlement by cutting “fixed costs,” which means shifting production to lower-cost regions.

The Need for Goals and Targets

The pro-manufacturing programs need to be more aggressive and more focused. In today’s world, where the U.S. has lost so much capacity in critical industries, insulation from low-cost foreign competition AND support for U.S. investment in rebuilding are needed. The insulation is required because foreign suppliers, especially China, will be relentless in trying to prevent the U.S. from rebuilding domestically and taking away their foreign market share. And U.S. financial support is needed to give U.S. companies the confidence that the U.S. won’t change course in a year or two.

Equally important, pro-manufacturing programs need to include specific targets, to be achieved over a long-term (say 5 years and 10 years) timeframe. Those targets need to be endorsed and embraced by the companies taking the financial support. Companies should be required to give back the subsidy money if the targets aren’t hit. In this way, private sector expertise will be incorporated to generate realistic, achievable targets.

The problem with today’s pro-manufacturing programs is that the goal is often unclear, left by Congress for different participants to interpret differently.

A good example is the CHIPS Act. This law aims to build up U.S. microchip manufacturing capability and, in the view of some, prevent China from dominating the global microchip industry. So Micron Technologies, the sole U.S.-based maker of memory chips, is receiving billions of dollars under the CHIPS Act to help it build a huge chipmaking fab in upstate New York. That’s a great step in the right direction.

Yet earlier this month a U.S. tech publication reported that Micron has just agreed to build a $602 million facility in Xi’an, China to test and package memory chips[5]. It’s very possible that ten years from today China may manufacture more microchips than the U.S., and China may yet dominate the global market. It’s even possible that in a few years, Micron (a U.S. company) may manufacture more chips in China than in the U.S. If the goal of the CHIPS Act was to maintain U.S. production above a certain threshold, or to maintain U.S. production above China’s, then those targets should be explicit. The use of “free” subsidy money, dependent only on building facilities that are largely paid for by the federal and state government, leaves private companies to go elsewhere (like China) and demand the same subsidies to build there.

Industrial Policies for the 21st Century

Two visionary members of Congress, Sen. Marco Rubio (R-FL) and Rep. Ro Khanna (D-CA), have proposed a more exciting and meaningful industrial policy to meet America’s current challenges. Together they co-wrote and introduced the National Development Strategy and Coordination Act (H.R.514 and S.99), a bill that would put the government in the business of laying out and leading a national industrial strategy. In an insightful essay[6] earlier this year, Sen. Rubio pointed out that such strategic economic planning and government involvement (while leaving the execution to the private sector) has been a part of American history since the founding of the republic. In a ringing endorsement of industrial policy, Sen. Rubio wrote: “The collapse of American manufacturing correlates with falling employment and societal decay in rural Appalachia and downtown Baltimore alike. But conservative industrial policy could correlate with the inverse, breathing new life — and freedom — into a divided and downcast nation.”

Rep. Khanna expressed a similar view. In a speech at Stanford University a year ago, he called for a new “economic patriotism” for America: “Let’s have a chips act for aluminum, for steel, for paper, for microelectronics, for advanced auto parts and for climate technologies. To succeed, we’ll need expedited permitting for national projects, conditional on companies paying a prevailing wage, meeting environmental standards, and not engaging in stock buy backs.”[7]

Industrial policies, including import protection and domestic stimulus, have begun. They have further to go. But they are on the right track.

[1] David Ricardo, The Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, Dover Edition, 2004 (1817), pg. 81.

[2] See my two-part article, The American Way of Growth for more on this history.

[3] Dani Rodrik, On Productivism, March 2023, pg. 1.

[4] Alberto Cavallo, Gita Gopinath, Brent Neiman, Jenny Tang, Tariff Passthrough at the Border and at the Store: Evidence from U.S. Trade Policy, Oct. 2019, pg. 3.

[5] Christopher Harper, Micron is building a new packaging and testing plant in China despite sales ban—largest American chipmaker expands abroad, Tom’s Hardware, April 2, 2024.

[6] Sen. Marco Rubio, Industrial Policy, Right and Wrong, National Affairs, spring 2024.

[7] Rep. Ro Khanna, Constructive Rebalancing with China, Prepared Remarks at Stanford University, April 24, 2023.