A steel mill in Huger, S.C., in April. The president signed executive orders in April calling for the Department of Commerce to launch investigations into whether imports of steel and aluminum were harming American national security.

[Ana Swanson | October 26, 2017 | New York Times]

WASHINGTON — Frustration over President Trump’s delay in imposing the stiff tariffs he has promised on imports of foreign steel and aluminum is morphing into a fight over two of Mr. Trump’s trade policy nominees.

Senator Chuck Schumer of New York, the Democratic leader, said on Thursday that he would block the nominations of Gilbert B. Kaplan for the top international trade post at the Commerce Department and Nazakhtar Nikakhtar for assistant secretary of commerce until the White House advanced a stalled effort to protect American metal producers from cheap Chinese products.

Mr. Schumer’s timing is intentional, coming just ahead of Mr. Trump’s trip to Beijing early next month. Blocking the president’s nominees is one of the few levers Democrats have to try to force Mr. Trump to move ahead with his trade agenda, which is supported by labor unions and some Democrats, but opposed by some in the president’s own party.

The nominees can be approved even with Mr. Schumer’s hold, but it will force the Senate to go through a more time-consuming cloture vote for approving officials, delaying these and other nominations in the pipeline.

In an interview on Thursday, Mr. Schumer said he was frustrated that a process the president began this spring as a precursor to imposing tariffs had not culminated in any action and had actually made things worse for United States companies.

When the administration announced the investigation, “we felt, O.K., they’ve got the message. But they’ve just dragged their feet and delayed and delayed,” Mr. Schumer said. “The bottom line is the president has been a total paper tiger on this issue, and as a result, we feel the need to hold up nominees for the Commerce Department.”

The delays in imposing the tariffs appear to have further worsened conditions for the American steel industry, which was already struggling financially with a global glut of cheap metal. To get ahead of the tariffs, foreign manufacturers appear to have shipped more steel and aluminum into the country. Steel imports rose 20 percent in the five months since the investigation was announced in April, compared with the previous five months, the American Iron and Steel Institute said on Thursday.

The import surges have helped fuel more layoffs and plant closings, according to Scott Paul, the president of the Alliance for American Manufacturing, which represents steel companies and workers. According to Mr. Paul, that includes layoffs of 180 workers at the Dura-Bond Industries plant in Steelton, Pa., and 150 workers at ArcelorMittal’s rolling mill in Conshohocken, Pa.

The president signed executive orders in April calling for the Department of Commerce to open two separate investigations into whether imports of steel and aluminum were harming American national security. Initiated under the rarely used Section 232 of a 1962 trade law, the investigations gave the president broad authority to impose tariffs or other restrictions on imports. Proponents of such measures said a glut of Chinese metal was depressing worldwide prices to such low levels that American manufacturers could not remain in business.

The administration said it would announce a decision by the end of June. Throughout the spring and summer, those in the steel and aluminum industry in the United States and abroad waited for tariffs or other measures, which they thought would be sweeping and imminent.

Senator Chuck Schumer, the Democratic leader, said he would move to block two Commerce Department nominees, one of the few levers Democrats have to try to force the president to move ahead with a trade agenda supported by labor unions and some Democrats, but opposed by some in the president’s own party.

Al Drago for The New York Times

“Wait till you see what I’m going to do for steel and your steel companies,” Mr. Trump told a crowd in Cincinnati on June 7. “We’re going to stop the dumping and stop all of these wonderful other countries from coming in and killing our companies and our workers. We’ll be seeing that very soon. The steel folks are going to be very happy.”

But the measures never materialized. In July, the president told The Wall Street Journal that he had decided to wait until the administration had finished “health care and taxes and maybe even infrastructure.”

On Sept. 19, steelworkers came to Capitol Hill to meet with senators and urge them to move the investigation forward. Billy McCall, the president of the local United Steelworkers union in Gary, Ind., said he saw measures to protect steel plants as a necessity. “We’ve been fighting a trade war for some time,” he said.

But support for the steel and aluminum measures has been far from unanimous. American industries that buy metals to forge into other products, including food packagers and automakers, complained that tariffs could raise their costs and shrink their profits.

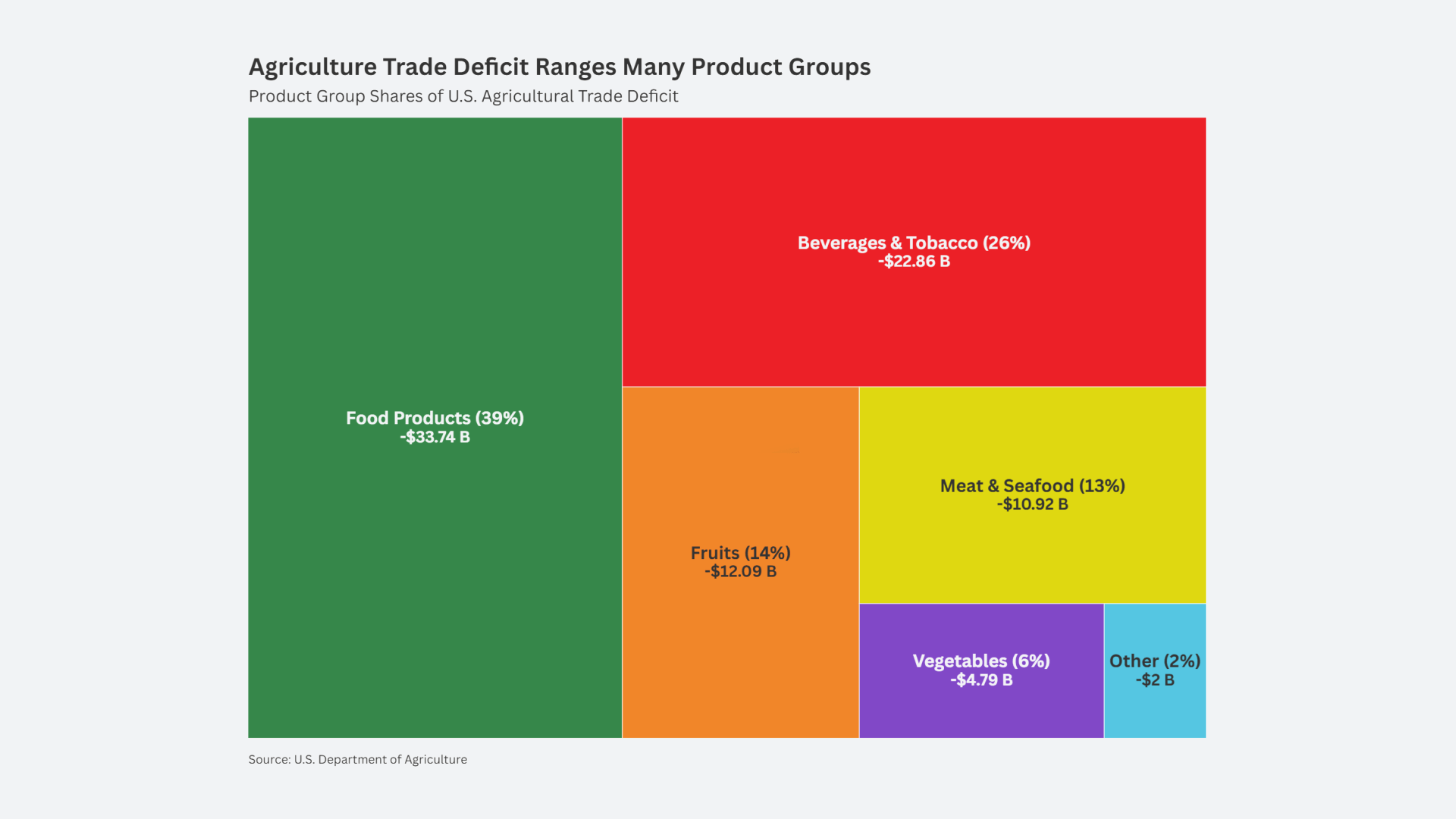

The European Union and foreign countries that supply metals to the United States, including Canada and South Korea, also protested, arguing that the United States should work with other countries to act against China, not retaliate against its allies. The Department of Defense argued that import restrictions could raise the price of its equipment, while the Department of Agriculture said it feared foreign partners would retaliate against American food exports.

In a letter sent Wednesday, Mr. Schumer and other Democrats urged the Commerce Department to take action before Mr. Trump arrived in Beijing on Nov. 8. But the White House may be hesitant to introduce such an aggressive policy before an important diplomatic visit.

The move is part of a broader fight over Mr. Trump’s promises to radically alter trade policy, which has largely been subsumed by other priorities, like the tax overhaul and the nuclear threat from North Korea. It is also a sign of the continued challenge the administration faces in creating policies to confront China economically while still preserving a strategic partnership.

Mr. Trump came into office saying that China’s economic competition was one of the biggest challenges facing the United States, but the administration has struggled to put together a comprehensive strategy to deal with it.

The administration did press China for significant cuts to its steel capacity during a visit to Washington in July, but the Chinese refused to accede to such big reductions. Since then, it has begun an investigation into intellectual property violations by the Chinese and is reportedly working on a more comprehensive trade approach. Both have yet to be unveiled, and it is unclear to what extent these plans or their components will be discussed during Mr. Trump’s Beijing visit.

In the next few months, the administration could roll out several influential trade measures, including the results of these investigations. Mr. Trump also confronts major decisions on whether to impose tariffs to protect domestic makers of solar cells and washing machines, as well as whether to withdraw from the North American Free Trade Agreement.

By statute, the Commerce Department is required to deliver final reports on steel and aluminum to the administration by January 2018.