P&O Ferries is the largest operator of ferryboats between the British Isles and the European Continent, a $1.1 billion company carrying 10 million passengers a year. Two weeks ago, on March 24, P&O shocked its 800 employees by firing all of them. But it was less what it did than how it did it.

On that Thursday morning, it emailed all 800 employees a three-minute video informing them they were fired with immediate effect. Minutes later, security guards arrived at all P&O boats in Dover and other ports to escort the workers off. The security force was equipped with handcuffs in case any workers resisted. In the event there was little resistance. According to BBC News, some employees were in tears as they were escorted off the boats. Some had worked for P&O for over 20 years.

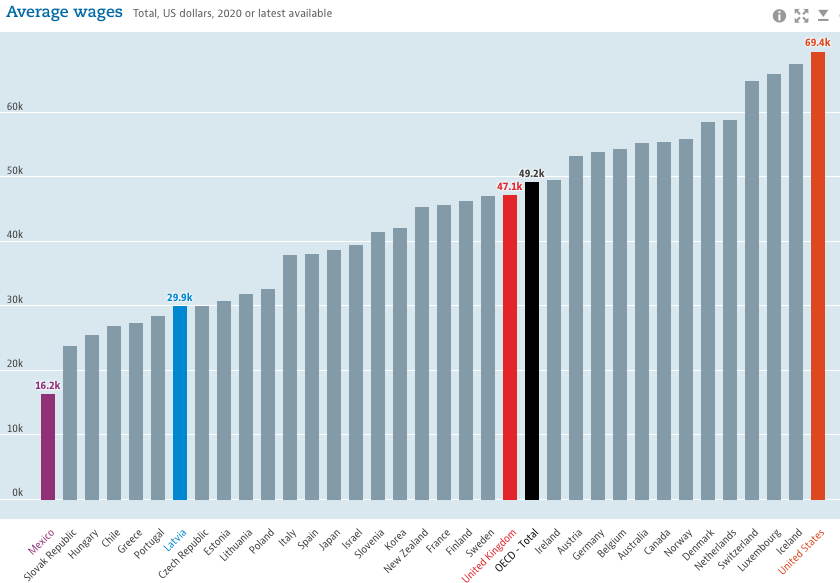

Although a historic company founded in 1835 in the heyday of the British Empire, P&O has belonged to a Dubai company, DP World, since 2019. As a Middle Eastern company controlled by a family of sheikhs, with all its ships registered in Cyprus for favorable tax treatment, P&O has apparently little concern for its public image in Britain. P&O fired its British crew to replace them with Latvians, who will be employed through an outsourcing agency. A look at Figure 1 below makes it clear why P&O took this action. If British and Latvian seamen are paid at the national average wage of their home countries, with this one move, P&O has cut its wage costs by 42%.

This is peak globalization. A multinational company can slash its wage costs by bringing in workers from a low-wage foreign nation. Even if Britain uses Brexit to deny the workers British residency or work visas, they can live in France or the Netherlands or Ireland, all choices open to them as Latvians since all are in the European Union.

As I have been arguing for around ten years, globalization is regression to a global mean. Putting British workers in competition with Latvian workers (and the workers of a dozen other eastern European nations) can only drive British wages down and eastern European wages up over time. Many economists, politicians, and other globalists have long claimed that global “efficiency” gains will outweigh the downward pressure on rich country wages in a global market for labor. They are fooling themselves and anybody who buys this silly argument. Economist Paul Samuelson pointed this out way back in a famous 1948 paper, where he showed that free international competition would force equality of price in tradeable goods and wages.

Globalization is bad news for American workers too. Take another look at Figure 1. The US is at the top end of the table, with average annual wages in 2020 of $69,392. At the extreme left is Mexico, where average wages are $16,230. The nation with the lowest wages in the OECD happens to be the one with which we share a lengthy border. China is not in the OECD, but if it were included, its wages would be similar to the Mexican level. Over time, if globalization proceeds without any protections or safeguards, U.S. real wages will fall to meet Chinese and Mexican wages. All the other claimed effects such as economic boom in poor countries or greater levels of trade may or may not happen, but economic theory and experience confirm that when two nations with different wage levels enter into completely free trade, wage levels converge.

Figure 1: Average annual wages, all OECD member nations with Mexico, Latvia, UK, OECD average, and US highlighted. Source: OECD.

Figure 1: Average annual wages, all OECD member nations with Mexico, Latvia, UK, OECD average, and US highlighted. Source: OECD.

Regression to a Global Mean

The downward pressure on living standards is in the long run a bigger cost of globalization than the jobs lost. People frequently talk of jobs lost, with common estimates that 1 million U.S. manufacturing jobs have been lost to Mexico and some 2.5 million jobs lost to China in the past two decades. But the slow, steady grinding down of U.S. real wages by international competition with the poor countries of the world is a broader and more relentless phenomenon, affecting millions of employed American workers, who don’t lose their jobs but instead find their living standards steadily eroding. If the process is allowed to continue, it may take 50-75 years for wages paid to U.S. workers (outside of industries sheltered from international competition) to match Mexico’s, and it may take 30-40 years for British wages to match Latvian wages. The process will be faster in Europe, because the level of economic integration is greater and because most of the low-wage eastern European nations are democracies and they will allow wages to rise more quickly than will the dysfunctional Mexican government. As for China, while wages may rise, other forms of subsidy to their exports will continue to drive down U.S. wages.

The Pendulum Swings Towards Deglobalization

And yet we seem to be reaching a turning point. A national consensus is gathering force that we now need to move beyond globalization and begin the deglobalization process, essential for rebuilding our economy, achieving greater income equality, and restoring national security.

This is precisely what thoughtful, influential billionaire investor, Howard Marks of Oaktree Capital Management, argued recently in the Financial Times when he said that after 30 years, the “pendulum of globalization” is now swinging in the other direction, towards onshoring and greater national self-sufficiency.

According to Marks: “Choosing to rely on a hostile neighbor for essential goods is like building a bank vault and contracting the mob to supply it with guards.” Marks recognized the economic impact of globalization: “offshoring…led to the elimination of millions of U.S. jobs and the hollowing out of the manufacturing regions and middle class of our country.” He went on to say that reshoring of U.S. industry will: “improve importers’ security, increase the competitiveness of onshore producers and the number of domestic manufacturing jobs, and create investment opportunities in the transition.”

Larry Fink, chairman, of $10 trillion investment manager BlackRock, has also publicly recognized that we are at the beginning of a new phase of what he called “deglobalization, inflation, and the energy transition.” While Fink claimed that he still believed globalization was a good thing, he conceded that the Russian attack on Ukraine marked a turning point where nations including the U.S. now need to pay closer attention to national security and reliable supply lines.

We’ve also seen greater recognition of the need for and the viability of deglobalization among political leaders. Congressman Earl Blumenauer, an influential Democrat who serves as chairman of the Trade Subcommittee of House Ways and Means, introduced a bill to block all Chinese sellers from using the de minimis exemption from duties which allows all shipments valued at less than $800 to enter the U.S. duty-free and inspection-free. If this bill passes, it will knock the heart out of Amazon’s business and the business of hundreds of other online stores selling cheap China goods which, as Rep. Blumenauer pointed out, sell dangerous merchandise and profit from forced labor in China. “Republicans and Democrats alike will have the opportunity to show they are pro-human rights, pro-environment, and pro-worker,” Blumenauer said.

Across the aisle, more and more Republicans are becoming outspoken on the need for deglobalization, motivated by national security, economic pressure, and cultural concerns. In a powerful speech last December, Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida called globalization “an economic, social, and geopolitical disaster.” Rubio focused on the damage that job loss has done to family structure and the self-respect of men and women who lose their job. “Lower prices alone can never make up for the fact that you lost the stability and dignity that comes from a good paying job,” Rubio said.

What Rubio did not say, but is equally important, is that the pressure for lower prices brings with it the pressure for lower wages as U.S. wages are forced, over time, to reach the same level as our international competitors. The claims that U.S. workers benefit from better education, more skills, or more capital investment per worker have been disproved by time.

Another fund manager now recognizing this is Stephen Jen, a former IMF economist and currency trader based in London. Under the headline “Trade Globalization Made the World Brittle,” Jen explained how this works in a recent note to clients:

“Many workers in the developed world suffered and their suffering was for a while silenced by the bribe that these affected workers would have access to cheap imported goods financed by cheap loans. Policymakers enabled this very dangerous equilibrium by justifying QE [quantitative easing] to fight low inflation, which was partly a result of trade globalization. Artificially low interest rates in turn justified big fiscal spending, bloated property prices, cheap personal loans, which helped dull the impact of workers in the developed world being marginalized. This was never sustainable…and I blamed the Davos crowd, including the likes of the IMF and the academics, for maligning anyone who challenged the concept of uncontrolled trade globalization, which was in overdrive from 2001…These days mainstream economists are largely silent about trade globalization, because they know what we know.”

Factory Closures in Ohio

However…although there is growing recognition that deglobalization is the new order of the day for the United States, the forces of globalization remain strong.

Two weeks ago, GE Lighting, now a subsidiary of private company Savant, announced it was closing two Ohio plants in Bucyrus and Logan, and laying off 175 workers. These plants made light units with LED lights. LEDs are rapidly overtaking the entire lighting industry due to their low cost, long life, and low energy consumption. A Department of Energy report called the 2020 LED Manufacturing Supply Chain pointed out that 94% of the LEDs purchased in the U.S. each year come from China. Chinese domination of LED manufacturing has been growing steadily for a decade. Although the Savant plant packaged LEDs and did not manufacture them, the closure just adds momentum to China’s campaign to dominate this industry.

LEDs are essential for automobiles, among many other applications. The virtual reality goggles and contact lenses of the future which will be worn by gamers but also by Special Forces of the military will rely on LEDs. The typical automobile has some 3,000 microchips, and several hundred of those are LEDs. U.S. carmakers can’t build cars without LEDs (to overcome the chips shortage, one European carmaker is actually making cars with an old-fashioned steel needle on a spring for the speedometer.)

The CHIPS Act now under consideration in Congress will do nothing to address our LED dependence on China. While the pendulum is swinging back towards deglobalization, the federal government and Congress need to be more engaged in the details of our supply chains. They need to put in place the sticks and carrots that get manufacturers like Savant to favor the U.S. for manufacturing locations and carmakers and other customers to buy American instead of buying cheap and Chinese. We need to reduce dependence on extended unpredictable supply lines, especially when dominated by hostile nations. There are many other such industries, where we in the U.S. have lost almost our entire productive capacity and aggressive action is needed.

Yet, many observers who criticize the role of Wall Street often overemphasize its influence. The barrier to rebuilding the U.S. economy is less Wall Street than it is the managers of the multinationals who see the quickest route to profit in cutting cost.

Smart investment managers like Howard Marks will make money whether the trend is towards globalization or deglobalization. But corporate managers who lack a creative business strategy have for over 20 years turned to globalization as a way to drive down costs. While an individual company can boost its profits this way, the collective result is to depress U.S. job opportunities and wages, while strengthening our economic competitors. Contrary to the pablum from mainstream economists, there is a global competition for the best industries, the best jobs, and the best economic growth. Senator Sherrod Brown outlined the problem well in his statement on the GE Lighting closures. He said:

“Corporate greed—aided by decades of underinvestment, bad trade policy—which these corporations lobbied for—and worse tax policy—which special interests also lobbied for—all drove production overseas. It left us reliant on other countries—too often our economic competitors. It exposed us to supply shocks. And it gutted our middle class.”

As the pendulum swings back to deglobalization, the challenge facing us is to turn around the mentality of the corporate elite managing our largest corporations.