Editor’s note: If the phase one deal is pronounced dead, China decoupling becomes even more likely.

Remember the phase one trade deal that the Republican Senate really wanted President Trump to ink with China (or else no quick impeachment acquittal, some DC insiders have told me) — well, it’s on life support.

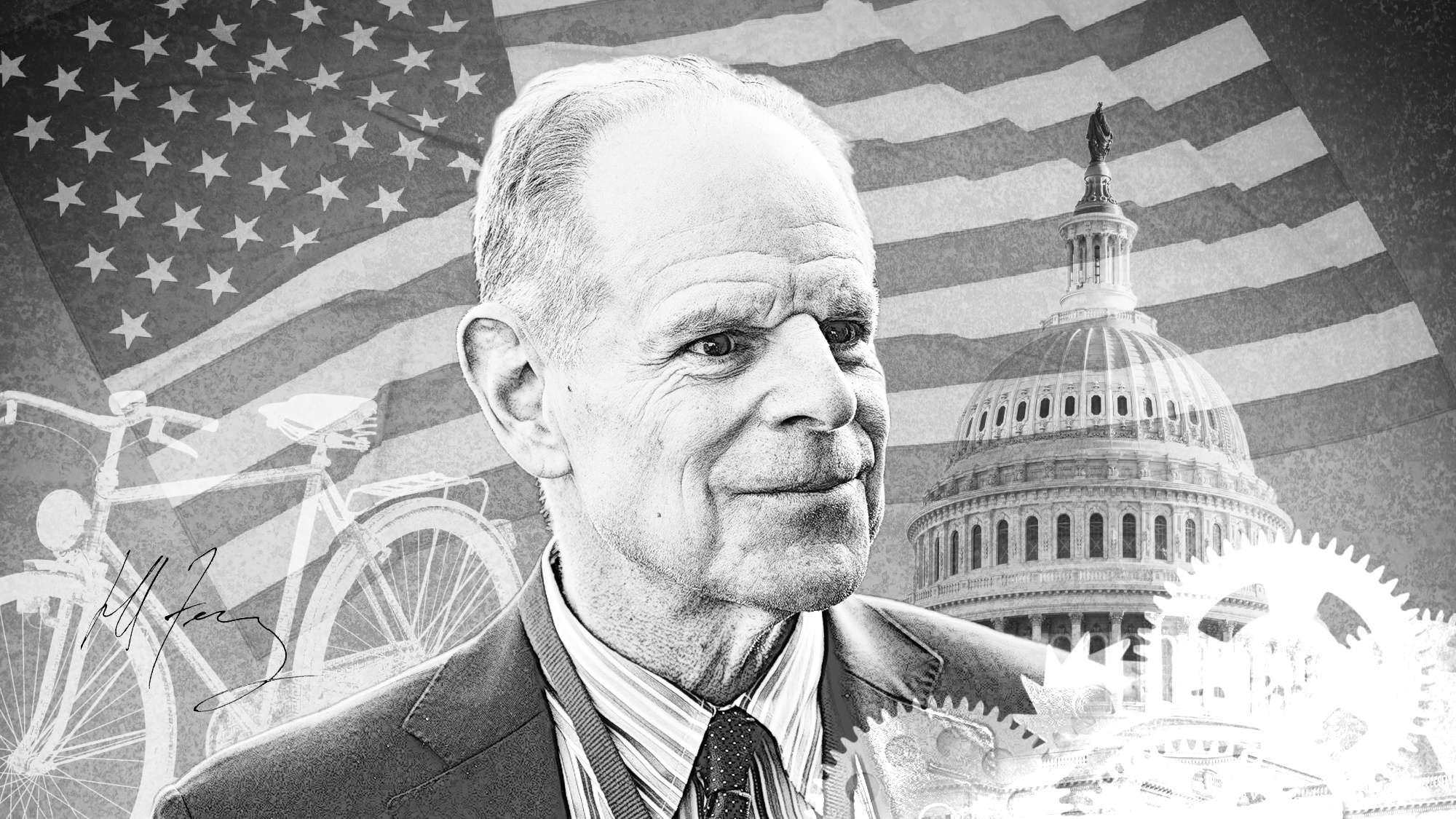

[Kenneth Rapoza | June 2, 2020 | Forbes]

“That phase one trade deal…we are left holding the bag,” says Lori Ann LaRocco, author of the book “Trade War: Containers Don’t Lie” and a trade columnist focused on supply chain data at industry publisher FreightWaves. “China has not met its obligations under the deal as of April 1 data and I think that trend still holds,” she says.

It sure looks that way.

It’s not Trump’s fault. No one in their right mind can say that Trump can force China to buy soybeans and pork meat, airplanes and LNG when its economy was crushed in a pandemic.

China does need to eat. China does need fuel, especially cheap fuel. It’s getting it elsewhere.

Here’s an example:

China is buying more Brazilian commodities and its not just because they’re fresh out of the ground. They are buying more than usual, meaning they will probably not need to buy much from the U.S. during crop season in the fall. We shall see.

For now, China accounted for 40.4% of Brazil’s exports in May. Despite the pandemic, despite weak economic growth, China has become an even bigger market for Brazil than ever before while other markets have shrunk. China bought 35.2% more from Brazil in May 2020 than it did in May 2019. So far this year, China has imported 15.4% more from Brazil than it did a year ago. Considering most of what it imports from Brazil is agricultural commodities and fuel, two items it promised to buy from the U.S., it seems fairly safe to say that the phase one trade deal is as strong as a wet noodle.

Like last year, and the year before that, China is telling its private companies not to buy American.

China imports from Brazil have increased by over 30% from the same period last year. Most of this is … [+]

Getty

Chinese state-owned companies suspended purchases of U.S. food items recently in response to Washington’s decision to strip Hong Kong of its privileged bilateral trade status.

A breakdown of the phase one deal, concluded in January after complex and lengthy negotiations, looks more likely today than it did at few weeks ago.

Chinese state-owned companies were told by Communist Party bosses to stop the purchase of pork and soybeans from the United States, in particular. Most of that is now coming from Brazil, the leading exporter of soybeans, having surpassed the U.S. because of the trade war. China is the biggest buyer of soy.

Phase two looks dead on arrival.

On May 29, Trump said that he would remove Hong Kong of its special status since Beijing’s creation of a national security law is deemed an encroachment on Hong Kong’s separate legal system.

The special status still stands. It is unclear when this would be stripped away. The Senate passed a bipartisan bill last year to do just that in case China encroaches more heavily on the Hong Kong pro-democracy movement; a movement Beijing sees as futile given that the autonomous region will be engulfed into mainland China within the next 27 years anyway under its agreement with the U.K. in the 1990s.

Under the phase one deal, China said it would increase the volume of purchases across numerous sectors in exchange for tariff rollbacks on more than $112 billion worth of goods.

The idea was to import around $200 billion worth of goods over the next two years, including about $50 billion in two years for oil and gas; $80 billion for engineering equipment; and $32 billion in agricultural products.

The Ministry of Agriculture said that China bought $1 billion worth of soybeans and $691 million worth of pork in the first quarter. If they did the same over the next three, that’d be $4 billion. If they doubled it, that’d be $8 billion, which is still far below what China normally imports from American soy farms.

In 2017, Brazil shipped 53 million tons of soy to China. It’s Brazil’s top two export item. It’s usually soy or iron ore that competes for number one to China.

The combined Brazilian exports of soy for 2018 and 2019 was 120 million tons, most of that due not to China being hungrier, but due to the fact that China turned to Brazil in an effort to hurt U.S. soy producers who have grown comfortably dependent on China over the last decade. Those days are over.

Brazil isn’t out of the woods, though. Their export economy is becoming more dependent on China. And that dependency means it will be harder for them to be independent on numerous geopolitical matters that could separate Brasilia further from Washington.

Read the original article here.