Key Points

- China needs to shift its economy away from investment and exports and towards domestic consumption. This would address its growing debt and overcapacity problems.

- China’s provincial and municipal governments face intense financial pressure. Some are having trouble meeting their bills.

- If it continues to rely on overinvestment, excessive imports, and financial repression, a debt meltdown is inevitable.

- The U.S., can help move China in this direction by continuing to reduce imports from China. This will put momentum behind a shift to domestic-led growth.

China’s economy is heading for an economic crisis as debt rises and the return on the huge industrial investment over the past twenty years continues to fall. China’s problem is that its economy is dependent on industrial investment and exports to generate the revenues that pay the bills of the national and local governments. That investment is in turn dependent on loans and subsidies from those same local governments as well as the state-controlled banks. According to Reuters, 12 regions are at high risk of debt default and have seen their investment activities curtailed by Beijing. China is fast approaching the point at which credit creation (or “money-printing” as some call it) loses its effectiveness and debt default and deflation follow.

The solution is to restructure the economy by allowing wages to rise and supporting a shift to a more balanced economy, i.e. increase domestic consumption reduce investment in loss-making heavy industry and exports. The west, especially the United States, can help this process along by limiting imports from China. This would be good for the Chinese economy and good for the U.S. too, to the extent reduced imports are replaced with American production.

From the fragmentary news reports we get in the west, it appears President Xi understands the problem. He has been trying to rein in local government debt and he often cites his vision of “dual circulation” meaning a growing domestic sector alongside a growing export sector. Yet he continues to encourage growth in chosen industries, such as those identified in the Made in China 2025 report. That conflict—between encouraging consumption but still encouraging heavy industry—is unsustainable. And the financial crisis of the local governments is the most dangerous link in the chain.

China’s national and local governments have less leeway to meet their financial obligations than is commonly thought. The local governments in particular are supporting continued investment in industry (with electric vehicles one of the hottest industries now) while at the same time the property crisis has cut back on their ability to finance that investment with land sales. Many Chinese provincial governments already carry debt worth over 100% of their local GDP (see Figure 1). Total local government debt is put at around 93 trillion yuan or $13 trillion by one estimate but as high as $23 trillion according to a private Goldman Sachs calculation.

Figure 1. The majority of China’s local governments are carrying debt at dangerous and unsustainable levels.

Source: Wind via GIS Reports Online

Industrial investment in overcrowded industries already selling at below cost and dumping on world markets does not make sense. Yet local governments continue to do so, hoping to create jobs and revenue in their local territories. According to one Communist Party official, more than a quarter of Chinese provinces already spend over half of their tax revenue on debt repayments. Many local governments are already having difficulties meeting the payrolls of teachers, bus drivers, and other local workers, according to one China expert at GIS Reports.

The short-term solution employed by the CCP since 2009 has been to expand bank credit available to banks, local governments, and industry, in other words to kick the can down the road and hope all the debt can be paid off in the future. But each bout of credit expansion has had less impact than the previous one, because investment returns are declining and in many cases are already well below the cost of capital. Also, credit expansion creates its own risks of widespread capital flight or a slide in the yuan which could start to look like a panic.

Exports are the longstanding recourse to boost revenue for Chinese companies and the local governments and banks that finance them. As Figure 2 shows, China runs the world’s largest trade surplus, having overtaken Germany in 2020. The current World Bank data goes up to 2022, when China’s trade surplus was $577 billion. Latest data from China shows the 2023 trade surplus at $823 billion. It has more than doubled in three years, driven by an export push on products like EVs and renewable energy equipment, weak demand for imports from its suffering consumers, and strong demand from Russia, its newfound trading ally.

Figure 2. China’s trade surplus has doubled in three years and is now the world’s largest.

Source: World Bank

But export growth is not a sure thing. Last year, China’s exports were $3.38 trillion, more than the U.S. and Japan combined. But they were down 4.6% from 2022 as a result of weak global demand, and the growing number of multinationals leaving China to produce elsewhere due to rising geopolitical tensions. Those tensions are likely to get worse as the European Union is close to enacting tariffs or some other form of restraint on imports of Chinese EVs.

Consumption is the Solution

The solution to the problem is to shift demand to consumption. The Chinese people are still poor by the standards of other large economies. The economic boom of the last 20 years has favored the rich. Shifting the economy to supply the needs of Chinese consumers will raise standards of living, encourage domestic spending, encourage more investment in domestically focused and profitable industries, and allow a scaling down of all those loss-making global industries. Crucially, it would generate tax revenue at the municipal, provincial and national level that would enable the Chinese government to pay its bills and avoid a revolution, which is of course the Communist Party’s worst nightmare. (Chinese Communist Party officials have not forgotten Tiananmen Square 1989.)

China has long had the highest ratio of investment to GDP in the world, at around 40%. Policies to support explosive growth of industrial investment were developed under Deng Xiaoping beginning in the late 1980s and carried on by his successors. These policies include the repression of wages, recycling profits into ever-more investment primarily in state-owned industries, supporting exports with tax breaks, subsidies and ambitious targets, and accelerating product development with widespread intellectual property theft.

China avoided the problems the Soviet Union faced of centralization eliminating all individual incentives by encouraging dozens of local governments to build and finance local industries, and let them compete with each other. But there is no mechanism for these companies to declare bankruptcy and withdraw from their markets when they are losing money. Instead they get new loans and stay in business. The Communist Party’s deep hold on the entire financial sector reduces the danger of a U.S.-style financial crisis. But that risk remains. In a deeply indebted economy, there is always the risk that something goes wrong, somebody fails to meet his obligations, and panic ensues.

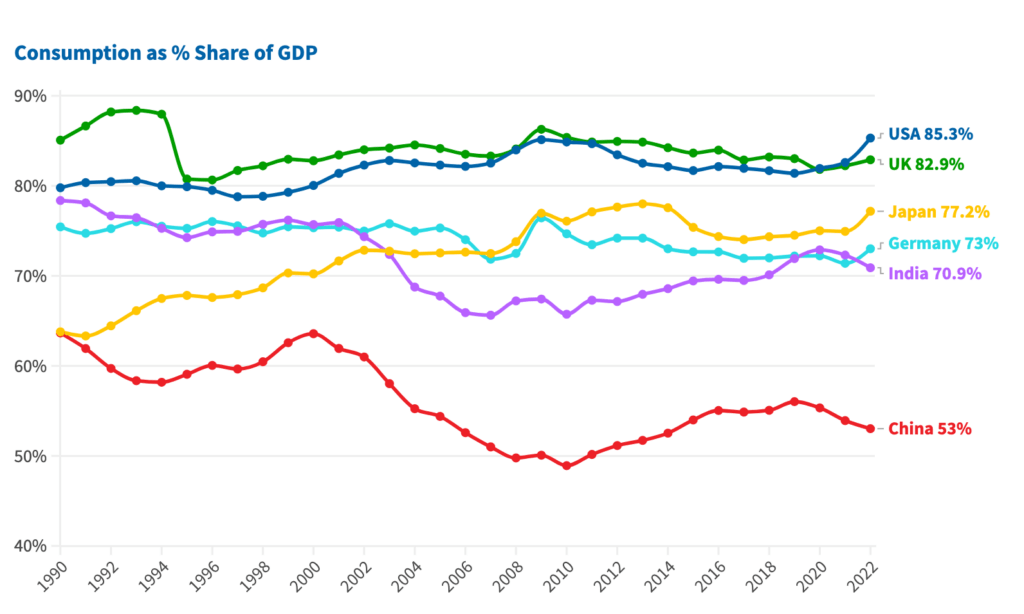

The solution is to scale down investment and exports, and raise domestic consumption. As Figure 3 shows, China’s consumption is unnaturally low for a modern economy. Every one of the six largest economies in the world has consumption at between 70% and 85% of GDP. China is at 53%, representing trillions of dollars of spending that should go into consumption but instead goes into investment and net exports.

At every investor meeting, Chanel, Louis Vuitton and Apple praise the (rich) Chinese consumer. The super-rich are highly visible in China. Every Chinese child and adult sees them on TikTok or Instagram. Yet these goods are out of reach for the vast majority. Financial repression for the masses has been perfected by the Chinese Communist Party.

Figure 3. China must raise domestic consumption to maintain economic growth and work off its debt mountain.

Source: World Bank

Xi’s government is aware of the problem. Measures have been announced by the government, but most appear cosmetic. GDP growth continues to outpace the growth of domestic Chinese consumption.

Until consumption grows substantially, and industrial investment is scaled back, China will continue to dig itself deeper into the hole of unsustainable debt. President Xi may appreciate the desperate need to take the Chinese economy to the next stage of development. But even if he does, the resistance he encounters from local government officials, banks, and many bureaucrats, as well as the fear that radical change could engender the very financial crisis it seeks to avoid, may tie his hands. And the Communist Party’s intense desire to control society fights against the idea of letting consumers enjoy the full fruits of their labors.

In that context, the growing worldwide reaction against excessive Chinese exports could ironically help China by hastening the necessary transformation of the Chinese economy. If China’s exports began to fall significantly, Beijing’s hand could be forced. Faced with the prospect of debt defaults, layoffs, and missed pay for municipal workers, it would have no choice but to announce a major new economic direction focused on domestic stimulus. A period of austerity would be needed, but in say five to eight years, China could work its way through its debt mountain and begin to see substantial growth as urban and rural consumers would gain access to the consumer goods that other Asian consumers already enjoy.