Bicycle imports slumped by 33% last year as American consumers cut back spending in the wake of the pandemic bike boom. Yet imports continue to dominate the U.S. market, with China as the largest source of imported bikes. Import market share rose slightly last year, reaching 97.8%, up from 97.5% in 2021. The U.S. bicycle market is one of the most overwhelmingly dominated by imports of all U.S. consumer goods markets.

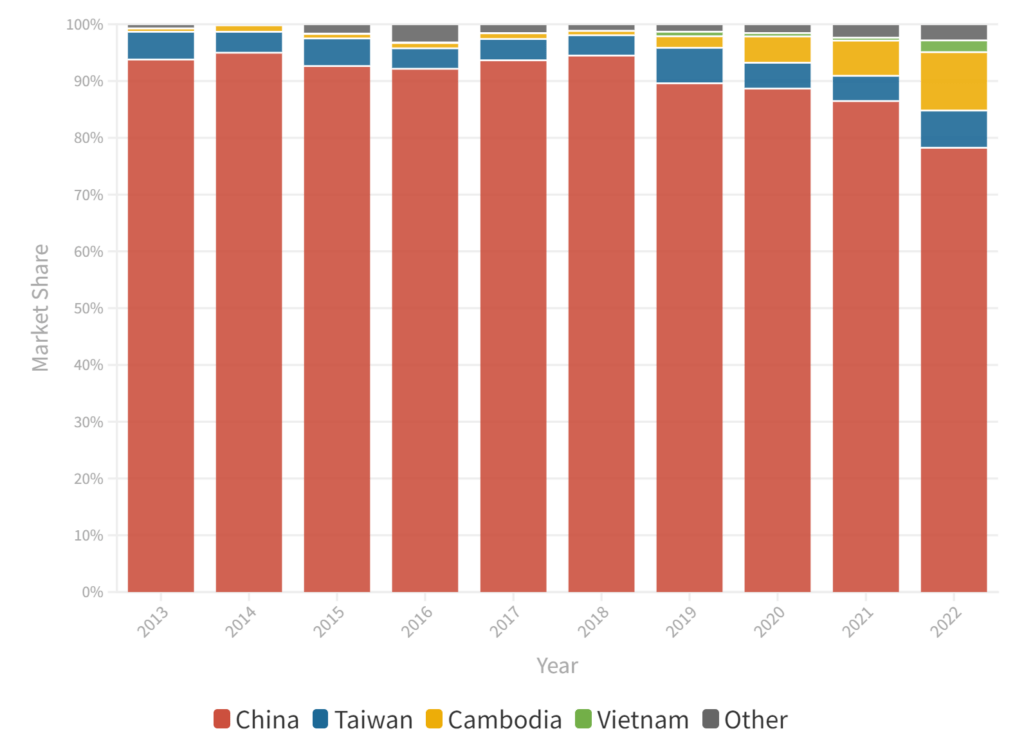

The Section 301 tariffs have had a significant effect on the official import figures. Imports from Cambodia and Vietnam have surged although many of those imports remain dependent on China for bike frames and components.

In 2018 and 2019, President Trump levied tariffs of 25% on most bikes and bike parts coming from China. Exclusions for certain types of bikes weakened the impact, but nevertheless substantial trade diversion followed. Cambodia was the biggest beneficiary. Cambodia went from around 100,000 bikes imported into the U.S. in the pre-Trump years to 1.34 million and a 10.1% market share last year (see Table 1). Vietnam also benefited, rising from close to zero in 2018 to 270,539 last year, or 2.0% of the U.S. market.

Table 1. U.S bicycle market dominated by imports (2022)

| Source | Volume (Units) | Market Share |

| Domestic Production | 300,000 | 2.2% |

| China | 10.2M | 76.5% |

| Cambodia | 1.3M | 10.1% |

| Taiwan | 856,150 | 6.4% |

| Vietnam | 270,539 | 2.0% |

| Total Imports | 13.1M | 97.8% |

| Total Market | 13.4M | 100% |

| Source: U.S. Census, Industry sources, CPA calculations | ||

China’s market share fell last year to 76.5% of the U.S. market, down by nine points. According to industry sources though, as many as three quarters of the bikes that came from Cambodia and Vietnam may have been mislabeled to avoid tariffs. Under U.S. Customs and Border Patrol rules, a bike’s origin is determined by where the frame is manufactured. If a frame is manufactured in China and then shipped to another country for final assembly, it should still be labeled “Made in China” for Customs purposes. China is the home of most of the world’s largest bike frame manufacturing facilities, based on mass production, low wages and poor working conditions that other countries cannot or choose not to duplicate. Many bike components used to build bikes in Cambodia, Vietnam, and Taiwan also likely came from China, according to industry sources. China’s bicycle industry serves the centrally-planned economy as a useful market for two giant industries where China has huge production and excess capacity: steel and aluminum.

Figure 1. China dominates bicycle imports but Cambodia, Vietnam shares grow as tariffs bite.

Retail sales figures for the bike industry are hard to come by, and those that are published generally do not include the large number of bikes purchased online. But it is highly likely that retail sales last year were well below the total of 13.4 million units imported and produced here, since bicycle retailers and manufacturers cite a large increase in bike inventory in their warehouses. The excess inventory problem is due also to the supply chain snafus in 2020 and 2021. During the pandemic, consumers rushed out to buy bikes as a safe form of exercise. Retailers and U.S. manufacturers found it hard to get bikes, with container shipping rates skyrocketing. In some cases it was simply impossible to get space in a container on a ship crossing the Pacific.

The bike industry was seduced by a “bicycle boom” that many thought would last beyond the pandemic. They placed large orders in 2021. Those orders finally started to land on west coast docks in late 2021 and early 2022, just in time for consumer purchases of bikes to slump as Americans went back to gyms, team sports, or the sofa.

The bicycle industry and its employees are feeling the pain. Specialized, headquartered in California and a large maker of a full range of bikes, announced a layoff of 8% of its workforce in January. Parlee, a boutique maker of high-end bikes, declared bankruptcy in February. Shimano, a Japanese maker of gears and brakes and the world’s largest bike component maker, recently projected a sales decline of 21% to $2.95 billion for 2023.

E-Bikes Are Booming…and Catching Fire

The e-bike sector is defying the bike downturn. The Wall Street Journal recently reported that e-bike sales rose 25% last year to 1.1 million units. That means Americans bought more e-bikes last year than electric vehicles. EV sales last year were around 800,000 units. E-bikes appeal to consumers for practicality—they can be used for shopping and other short trips, for exercise, for environmental reasons (no greenhouse gas emissions) and for saving money on gasoline. A growing variety of e-bike models, including off-road e-bikes and e-bikes designed to carry cargo or child seats, are pulling more consumers into stores. E-bikes appeal to the bike industry because the price tag is some five to ten times the price of an ordinary bike.

However, e-bikes’ lithium-ion batteries have become a major danger. Last year, the New York Fire Department recorded 220 fires due to e-bike batteries, leading to 147 injuries and six deaths. So far this year, the FDNY has been responding to three battery fires a week and one elderly woman has died. Unwilling to wait for the Consumer Product Safety Commission to act, the New York City Council passed a measure earlier this month that will require all e-bikes sold in New York to be certified to the UL2849 standard, and batteries when sold separately, to meet UL2271. Mayor Eric Adams is likely to sign that bill soon.

But that law will not regulate e-bikes or batteries purchased over the Internet, most of which come from China, where regulation is virtually nonexistent. The “de minimis” rule, by which anything valued at under $800 comes through Customs with no inspection or duty, compounds the problem. De minimis puts U.S. manufacturers who routinely follow U.S. safety laws at a tremendous disadvantage. It also hurts bike retailers, who pay local taxes and follow safety laws.

A case in point is Rad Power Bikes, one of the largest e-bike brands in the U.S. A Seattle company, Rad managed to position itself as a “technology innovator” and raised $329 million in venture funds. All its e-bikes are imported from China. In 2022 its aggressive growth backfired when it suffered three lawsuits: one from a Utah woman who claimed that a loose handlebar stem caused her to crash and injure herself, another from a homeowner in Pennsylvania who claimed a Rad bike battery set their house on fire, and a third from a California family whose 12-year-old daughter died when her friend’s Rad bike crashed. She was a passenger on the bike.

Rad settled two of the cases and denies causing the house fire case. However, last year, Rad did three layoffs of more than 160 employees and its founding CEO left the company. He was replaced by a veteran manufacturing executive, Phil Molyneux, who admitted Rad has made “mistakes.” In an email to customers, he pledged that the “new Rad” would have a “laser focus on safety and reliability.”

But since Rad outsources all its manufacturing to China, it is a challenge to control the safety of its products.