Business/Technology Explainer: What is the Cloud?

Key Points

- Big Tech has developed valuable software applications to store and manage data anywhere in the world

- There is a vigorous national and global debate about protecting consumer data and national security as copies of data can be kept anywhere in the world

- The four cloud computing companies want to shut down the debate by imposing a global “free flow of information” rule through misleadingly named “digital trade” provisions in future international trade agreements.

- Ambassador Tai was right to stop pushing digital trade provisions at the WTO until Congress, the public and the world determine what the best policy should be.

The dispute in Washington over so-called “digital trade” escalated last week. The central tension is mainly about how, or even whether, to regulate Big Tech’s “cloud” activities domestically and internationally. This escalation stemmed from U.S. Trade Representative Katherine Tai withdrawing certain U.S. proposals to the WTO that would limit countries’ autonomy to regulate internet-cloud services. As her spokesperson stated, the United States did not want to “prejudice or hinder those domestic policy considerations.”

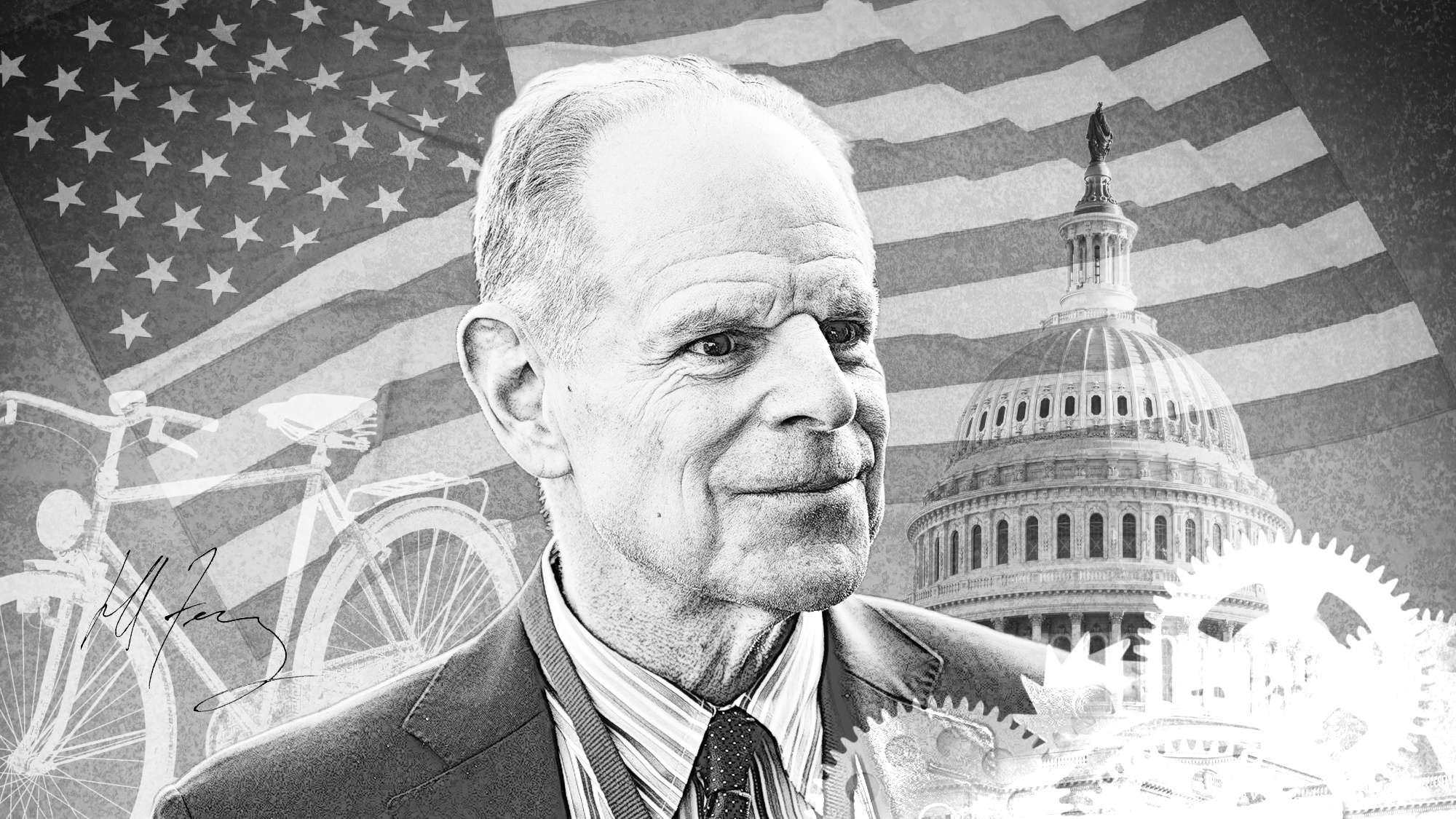

Her position was quickly attacked by Democratic Senator Ron Wyden, who said she was withdrawing previous U.S. support for the “free flow of information.” Senator Wyden is also the Chairman of the U.S. Senate Finance committee, which has jurisdiction over USTR.

But what is the cloud, and why does it matter? How should public policy balance the private business interests of a handful of cloud computing companies versus the interests of consumers and businesses who actually “own” the data. Is “digital trade” a misleading characterization of what is really not a trade issue? This explainer will shed light on these questions.

To many people not in the technology industry, the cloud is simply a place in the Internet where Apple stores your photos of your dog when you move them to its “iCloud.” But for those in the tech industry, the cloud was the most important new development in technology since the smartphone. The cloud refers to the global network of data centers owned by tech companies, and used to store and process corporate information.

Way back in the 20th century, companies stored all their data and their software applications in a group of servers each in their own closet or basement. In the beginning there was email and Microsoft Office. But over time, companies in every industry began to purchase more and more software applications to do more and more business functions. Before long they were using software to track their inventory, analyze their sales, monitor their supply chains, pay their employees, operate security on all their doors, hallways, and labs. It became hugely complex to manage all these software applications, buy all those computer servers, and protect them all against hackers.

In 2006, Amazon came up with the idea for a business of running all of a business’s software needs in centralized Amazon-owned data centers. They called this new business Amazon Web Services. Amazon took software invented by VMware to make servers much more flexible, and expanded and diversified it so that Amazon servers could handle hundreds of software applications for thousands of customers in each data center. The services proved so fast-growing and so profitable that the other tech giants jumped into the business.

Today virtually every sizable corporation does business with at least one and often two or three cloud providers. It also has a so-called “on-premise” data center in which it does certain tasks, but the more complex computing is typically done “off-premise” by a cloud provider. A good example is this recent press release, in which the London Stock Exchange announced it is transferring 17 software applications to the Oracle Cloud.

Table 1 shows that cloud revenue hauled in by the big four cloud providers in the most recent quarter totaled $60 billion. It’s growing at 18% a year, much faster than their other revenue. Cloud business is highly profitable, more profitable than selling packaged software. On an annual basis, the cloud is a $500 billion business, according to tech analysts Gartner. In addition to the big four below, there are many other multi-billion companies offering specific software that is only available via a cloud data center. They include names like Salesforce, Workday, Zoom, Shopify, Hubspot, and RingCentral.

According to tech industry sources, there are some 8,000 data centers in the world and about 2,600 of them are in the U.S. The big cloud providers—in the tech industry we call them the “hyperscalers”—own about 700 of these data centers, spread all over the world. Think of a hyperscale data center as a concrete building the size of a football field with dim lighting inside, packed with rows and rows of computer servers humming away, little blue lights blinking, all connected by hundreds of cables.

The cloud has always been an international business. Google pioneered the consumer cloud (such as free gmail email) and from early days, Google stored consumer email in multiple places around the world. Google told consumers this was to guarantee rapid access to users when they traveled. Another reason was that if one data center went down, another one could step in seamlessly and continue delivering email. For the business cloud, international shipment of data became even more important, because the costs were higher.

Once you have fitted your data centers with the thousands of servers (manufactured in China of course), the largest single cost for a cloud provider is the electricity to run all those servers and run the air conditioning to cool them. When I was in the tech industry, a German cloud provider told me that in the U.S. he paid 5 cents a kilowatt hour for electricity while in Germany he paid 30 cents. Thus, any software activity that could be done in the U.S for customers worldwide was done in the U.S. Fiber-optic connections and the speed of light made that possible. Only software activities that needed to be extremely (think microsecond) responsive (or that were required by local law) were done in the home country, and in a data center near the customer.

Politics Gets in the Way

The cloud is a great business model. Once a customer has all his data in one cloud, it’s extremely hard for him to move to another cloud provider. All your data has to be translated into applications compatible with the new cloud, often going back years. It’s a scary thought. In the tech industry, we call this lock-in. So costs have a way of inching up, year after year, making it even more profitable.

But along came the world’s politicians and the trade negotiators threatening to disrupt this business model. Some of them, in the U.S. and worldwide, objected to the cloud providers’ ability to move data around at will, usually unbeknownst to the customer. They began calling for “data localization,” meaning that data belonging to customers in any one country must stay in that country. Germany has been a leading proponent of this view. In a 2022 court case, a German court ruled that U.S. cloud providers could bid for cloud business but must keep German personal data within Germany. The European Union’s ruling Commission has been slower to decide on specific rules but generally favors greater support of customer privacy, customer control of their data, and data localization. See my colleague Charles Benoit’s article for further detail on the legal issues involved.

Until a week ago, the U.S. government has almost always supported the tech industry’s wishes on these issues. Those wishes included data globalization, in other words, the ability of cloud providers to move data wherever and whenever they want to.

Last week that changed. USTR Tai said the U.S. would stop pushing digital trade rules that guaranteed untrammeled data globalization. She took that step for domestic and international reasons.

Domestically, rules for data globalization would restrict the U.S. government’s ability to control the data of U.S. citizens and companies. Such a rule is already written into the USMCA trade agreement with Mexico and Canada. That rule appears to say that the U.S. could make no rule forbidding U.S. cloud providers from moving U.S. data to China. Of course, TikTok and Zoom already act this way, moving U.S. data routinely between the U.S. and China. So Tai, presumably backed by the White House, decided to draw a line and put all international agreements on data on hold until the Biden administration and Congress clarify what new requirements or regulations they want to put on Big Tech.

Internationally, data globalization is part of a familiar game plan. Before the big shift in trade policy that followed Donald Trump’s election in 2016, U.S. negotiators would typically go into trade negotiations determined to force foreign countries to open their doors wide to U.S. technology products and services. The problem with that was that those other countries were not naïve. They understood that such opening up was worth billions of dollars to Amazon, Microsoft, and their colleagues. In return, they asked for an opening up in other U.S. industries. That happened in the U.S.-Korea trade deal of 2011. The Koreans got more U.S. cloud services and America got more Korean cars. Unfortunately the riches of the cloud were concentrated on the west coast, while the job loss in the auto industry was concentrated in the Midwest.

There is a heated debate in Congress about consumer privacy and protection, who controls data and the national security aspects of where copies of our data should be located, including in China. Many countries in the world have decided to protect consumers. Ambassador Tai’s position, that trade should be worker-centric and take account of vulnerable, underserved populations, is entirely consistent with putting data globalization on pause, at least until Congress considers and decides what U.S policy should be.

The position of Sen. Wyden and various Republican supporters in favor of “free flow of information” is, in our view, naïve at best and misleading at worst. As it stands today, this so-called “free flow” ignores the right of the actual owners of the data, you and me, to ask where our data is being kept. The tech industry is free of any responsibility to manage our data responsibly. Tik Tok can keep American users’ data in China, as can Shein and Temu for analysis by their tech departments or by the Chinese Communist Party. There is no penalty for the endless stream of data leaks, hacking incidents, and so on. There is no recourse because all the big cloud providers operate the same rules: “we decide where your data goes, not you.”

On the other hand, some of the claims of the tech-hating far left are off base. The U.S. government can and should decide on sensible regulations for the tech industry, sensible privacy rules, and sensible national sovereignty rules. But tech regulation should not require tech companies to share their source code with the government or subscribe to other regulations that force software to be race-neutral or other unrealistic activities. The government does not need source code to insist on non-discriminatory results.

The tech companies’ privacy must be respected. They spend millions of dollars developing great software and the U.S. leads and dominates the world in this business. Source code is the crown jewel for every tech company. The government can and should allow investment, competition and innovation to continue, as long as it respects national sovereignty. But Big Tech should not be allowed to shoehorn its top lobbying issue, which is not a core trade issue, into global trade agreement negotiations to prevent the U.S. and other countries from improving legislative protections in the future.