U.S. Senator Bill Cassidy (R-LA) has released a discussion draft of a sweeping, ambitious bill titled the “Americas Act”. The bill states its aim to “establish a regional trade, investment, and people-to-people partnership of countries in the Western Hemisphere”. But unlike every other U.S. trade agreement in the last century, the Americas Act actually undertakes the necessary tariff reform to accomplish its aim. If implemented, it would succeed in driving industrialization and growth in the U.S. and throughout our hemisphere.

To understand why the Americas Act is special, one must understand the folly of the last 89 years.

Background

The U.S. has had three distinct periods relating to ‘free trade’ agreements (FTAs):

1789 – 1934, the successful era of tariffs for revenue and protection (2 FTAs): In the first 145 years of our republic, we had high tariffs that funded most of our government while also protecting domestic production. Indeed, trade agreements promising broadly lower tariff rates to foreign nations were used just twice: first with Canada in 1854, and then Hawaii in 1875. The U.S.-Canada tariff agreement was rescinded in 1866 as both nations successfully pursued further protective tariffs for economic growth, and with displeasure by the U.S. at British/Canadian support for the Confederacy. Hawaii was brought into the Union in 1898. (Frankly, both agreements accompanied open talk of annexation.) Other reciprocal tariff agreements were negotiated during this period, but were not ratified by the Senate. There were more limited tariff agreements that applied to a handful of commodities negotiated with Latin American countries in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but these did not last long or were never ratified.

1934 – 1947, the RTAA era wipes out most tariffs (30 FTAs): In 1932, Democrats took control of Congress and F.D.R. was elected President. An anti-tariff group of Congressional Democrats succeeded in getting one of their own, Cordell Hull, a Representative from Tennessee, confirmed as F.D.R.’s Secretary of State. That Congress then passed The Trade Agreement Act of 1934 (since misbranded the ‘Reciprocal’ Trade Agreement Act of 1934). This Act granted Hull sweeping power to cut tariffs via agreements with foreign nations. These agreements would no longer need to be ratified by the Senate. Furthermore, under the law, for each U.S. tariff cut for a particular product, the tariff cut for that product was eliminated for the whole world, not just the party to the deal. Secretary Hull entered into thirty of these agreements between 1934 and 1944, wiping out most U.S. tariffs.

Pictured at the top of this article is Cordell Hull (on the right), signing the U.S.-Brazil FTA of 1935.

In 1947, Hull’s 30 FTAs were collapsed into the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), a non-reciprocal tariff agreement with 22 other nations. The GATT persists today and now has 164 nations, see our “GATT at 75” here for more.

1947 – Present Day, the GATT era limits the utility of new FTAs. By 1950, the average rate of duty paid on goods imported into the U.S. had fallen to 5.8%, and 60% of all goods were imported duty-free. This applied to the whole world, including the Soviet Union and other communist nations. This was untenable. In response, President Eisenhower signed into law the Trade Agreements Extension Act of 1951. With this law, we’d cease to be a dumping ground to the Soviet empire. The U.S. tariff schedule was split into a “Column 1” and “Column 2”. Column 1 contains negligible tariffs for GATT countries and other non-communist countries, whereas Column 2 contained our higher tariffs from the last Congressionally passed tariff (the Tariff Act of 1930, a.k.a. Smoot-Hawley). Section 5 of the 1951 Act directed that communist nations be moved to Column 2. Column 1 and 2 remain today, but Belarus, Cuba, North Korea, and Russia are the only countries in Column 2.

Throughout the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, the main legislative action in tariff policy was working to move countries from Column 2 to Column 1 as they shed communism. See our guide on Repealing China’s MFN status for more on Column 1 vs. Column 2, and expanding tariff preference programs.

Tariff Preference Programs in the GATT era have limited effect

In the 1960s, multinational enterprises concerned about ‘import substitution’ industrial policies in the non-Communist developing-world hatched a plan. They formed a group called the “Committee for Economic Development”, which argued that if poor countries protected the multinationals’ investment, they should be eligible for waivers of the negligible tariffs the U.S. had in Column 1, thus making them more attractive to further U.S. investment. In 1974, Congress passed the General System of Preferences (GSP) to do just that, which today offers unilateral tariff cuts to 119 countries, including Brazil.

Congress’ deployment of GSP was actually condemned at the time in a resolution by the Organization of American States due to the legislated criteria, which included not joining the OPEC oil cartel, thus excluding Ecuador and Venezuela.

Nonetheless, given our negligible Column 1 tariffs, further GSP tariff cuts – e.g., going from 2% to 0% – proved to have little effect on sourcing decisions. A Congressional Research Service report on GSP states that “Developing countries have expressed concern about the overall progressive erosion of preferential margins as a result of across-the-board tariff reductions” via the GATT.

Despite GSP’s sweeping coverage of 119 countries, only about 4% of U.S. merchandise imports are entered through GSP today. As most imports face 0% tariff, there is no incentive to even prepare the certificate of origin necessary to elect GSP status.

A final quick note about FTAs in the GATT era: between 1947 and 1989, the U.S. signed only one FTA, with Israel in 1980. In 1989, a U.S.-Canada FTA went into force, which in turn was subsumed into NAFTA in 1994. The North American FTAs were driven in large part by foreign investment concerns, particularly with regard to energy. Under NAFTA, the U.S. tariff on cars, at 2.5%, went to 0%, but this was not the reason for a rapid displacement of U.S. auto jobs to Mexico. The reason was the secured investment environment and lower wages in Mexico. Under the George W. Bush Administration, FTAs were entered into with 13 new countries, but these too have had little effect at their stated aims. (We’ll address a notable exception in CAFTA-DR below).

As of 2023, the United States has free trade agreements with twelve of the largest Western Hemisphere economies, and tariff preference programs covering the rest. These preferential tariff agreements and programs haven’t moved the needle, even with the support of dedicated government finance programs like the Inter-American Development Bank, established in 1959.

What makes the Americas Act different

Unlike everything tried in the last century, the Americas Act recognizes that using our giant marketplace to encouraging sourcing in the Americas only works if we first stop being a dumping ground to the whole world. So to that end, it tackles the two big problems at our ports: chronic nil-to-zero tariffs, and the de minimis loophole.

Americas’ Act tariff reform

Section 213 of the Americas Act undertakes the critical tariff reform needed to actually re-shore and near-shore in this Hemisphere. It undoes the tremendous damage of Cordell Hull, who eliminated almost all our tariffs for the whole world, thus making any tariff preference program or reciprocity deal impotent.

Section 213 of the Americas Act undertakes the critical tariff reform needed to actually re-shore and near-shore in this Hemisphere. It undoes the tremendous damage of Cordell Hull, who eliminated almost all our tariffs for the whole world, thus making any tariff preference program or reciprocity deal impotent.

Indeed, for generations, it’s been U.S. law – see 19 U.S.C. 2136(c) – to only expect tariff reciprocity with Canada, Europe, and Japan. (Thank heaven Henry Clay isn’t alive to see what we’ve done with our inheritance…)

Section 213 puts an end to this suicide. It states that

The United States Trade Representative shall pursue approximate tariff reciprocity among WTO members–

(1) by commencing negotiations under article XXVIII of GATT; and

(2) by committing to increase rates of duties on imports into the United States if other countries do not decrease their rates in line with those rates in Schedule XX.

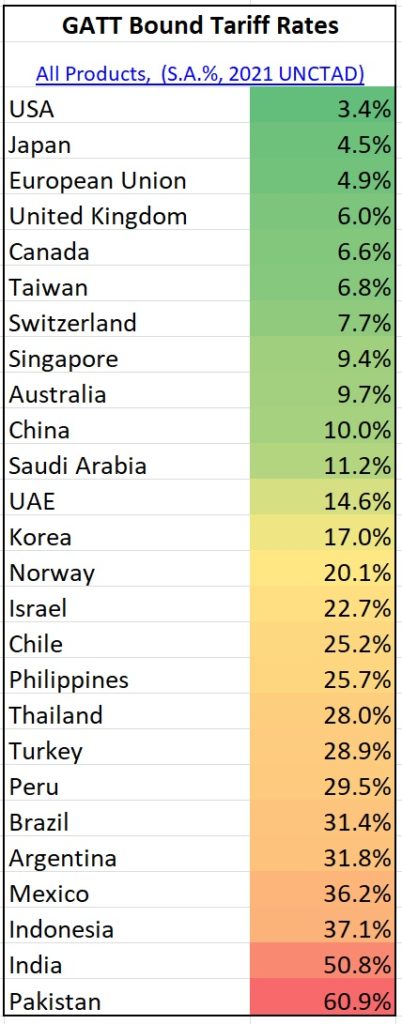

Emphasis added. “Schedule XX” refers to the U.S.’ Schedule of Concessions to the GATT, wherein the U.S. commits to an average 3.4% tariff to every WTO country. (See CPA guide to learn more about tariff reform, and about the GATT Art. XXVIII process).

There is little-to-no chance the countries of the world will come down close to our 3.4%. India has been steadily increasing its across the board tariffs in recent years with tremendous success. Raising our bound tariff rates to be ‘middle of the pack’ with WTO members would likely move us from 3.4% to something closer to 34%, a 10x, increase. But even going to something like Norway’s 20% would be a profound revenue event for the United States. Our China 301 tariffs apply to only about one-third of what China sends us in a given month, at an average rate of around 20%, and those limited tariffs have still helped shift sourcing out of China, while also providing a $50 billion per year windfall to the U.S. Treasury.

A policy of GATT Tariff Reciprocity as detailed in Section 213 is a win for America, and also a win for every country with whom we extend preferential tariff rates. It will supercharge sourcing to U.S. GSP beneficiaries, and even more so our FTA partners, as well as domestically.

CAFTA-DR’s “Yarn Forward” tariff rule illustrates ‘Near-Shoring’ success using high(er) tariffs

CAFTA-DR, our FTA with Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, as well as the Dominican Republic, is one ‘near-shoring’ story that did enjoy some success, in terms of apparel and textile products. We still have something like an average 14% tariff (low, but high by woeful U.S. standards) for clothing. And we thankfully excluded apparel from GSP tariff waivers. For these reasons, CAFTA-DR had an opening: apparel made in CAFTA-DR countries can be imported into the U.S. duty free if the apparel is made with American textiles (fabrics). This is known as the ‘Yarn Forward’ rule. Saving the average 14% was enough to lead many large clothing brands to make apparel in Central America, using U.S.-made textile inputs. Although that success is now largely being lost thanks to our de minimis loophole…

Americas Act attacks de minimis loophole

Little known outside trade circles a few years ago, the deluge of imports flooding in via de minimis – millions per day, a billion per year – without any scrutiny or revenue measures is high in Congress’ sights. (See CPA’s de minimis guide for more)

Senator Cassidy wants the Americas Act to tax the loophole, and then use the tax receipts to help shift sourcing from China to our own Hemisphere, a laudable goal. Senator Cassidy told the Miami Herald:

Much of the funding [for the bill] would come from closing a loophole by which China sends more than $100 billion a year to the United States in goods tariff free. Under current U.S. Customs’ so called “De Minimis” rules, individual packages worth less than $800 from anywhere don’t pay U.S. duties.

Between the increase of tariffs generally, and the taxing of de minimis shipments, the U.S. Treasury will be awash in new revenue, and our supply chains will certainly shift to countries with whom we have preferential tariffs arrangements. The bill envisages more trade finance tools to help the shift, but in the event our GATT/WTO tariffs do increase into the double digits, it’s hard to believe any more incentive would be needed.

Senator Cassidy deserves credit, especially as a member of the Senate Finance Committee, for being willing to take the bold and courageous steps actually necessary to create hemispheric supply chains. Members of Congress and Presidents have spent decades talking about Western Hemisphere integration, but Senator Cassidy is the first to introduce the necessary tariff and trade policies to get serious about it.

Americas Act Addresses Key Failure of Past Trade Deals

U.S. Senator Bill Cassidy (R-LA) has released a discussion draft of a sweeping, ambitious bill titled the “Americas Act”. The bill states its aim to “establish a regional trade, investment, and people-to-people partnership of countries in the Western Hemisphere”. But unlike every other U.S. trade agreement in the last century, the Americas Act actually undertakes the necessary tariff reform to accomplish its aim. If implemented, it would succeed in driving industrialization and growth in the U.S. and throughout our hemisphere.

To understand why the Americas Act is special, one must understand the folly of the last 89 years.

Background

The U.S. has had three distinct periods relating to ‘free trade’ agreements (FTAs):

1789 – 1934, the successful era of tariffs for revenue and protection (2 FTAs): In the first 145 years of our republic, we had high tariffs that funded most of our government while also protecting domestic production. Indeed, trade agreements promising broadly lower tariff rates to foreign nations were used just twice: first with Canada in 1854, and then Hawaii in 1875. The U.S.-Canada tariff agreement was rescinded in 1866 as both nations successfully pursued further protective tariffs for economic growth, and with displeasure by the U.S. at British/Canadian support for the Confederacy. Hawaii was brought into the Union in 1898. (Frankly, both agreements accompanied open talk of annexation.) Other reciprocal tariff agreements were negotiated during this period, but were not ratified by the Senate. There were more limited tariff agreements that applied to a handful of commodities negotiated with Latin American countries in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but these did not last long or were never ratified.

1934 – 1947, the RTAA era wipes out most tariffs (30 FTAs): In 1932, Democrats took control of Congress and F.D.R. was elected President. An anti-tariff group of Congressional Democrats succeeded in getting one of their own, Cordell Hull, a Representative from Tennessee, confirmed as F.D.R.’s Secretary of State. That Congress then passed The Trade Agreement Act of 1934 (since misbranded the ‘Reciprocal’ Trade Agreement Act of 1934). This Act granted Hull sweeping power to cut tariffs via agreements with foreign nations. These agreements would no longer need to be ratified by the Senate. Furthermore, under the law, for each U.S. tariff cut for a particular product, the tariff cut for that product was eliminated for the whole world, not just the party to the deal. Secretary Hull entered into thirty of these agreements between 1934 and 1944, wiping out most U.S. tariffs.

Pictured at the top of this article is Cordell Hull (on the right), signing the U.S.-Brazil FTA of 1935.

In 1947, Hull’s 30 FTAs were collapsed into the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), a non-reciprocal tariff agreement with 22 other nations. The GATT persists today and now has 164 nations, see our “GATT at 75” here for more.

1947 – Present Day, the GATT era limits the utility of new FTAs. By 1950, the average rate of duty paid on goods imported into the U.S. had fallen to 5.8%, and 60% of all goods were imported duty-free. This applied to the whole world, including the Soviet Union and other communist nations. This was untenable. In response, President Eisenhower signed into law the Trade Agreements Extension Act of 1951. With this law, we’d cease to be a dumping ground to the Soviet empire. The U.S. tariff schedule was split into a “Column 1” and “Column 2”. Column 1 contains negligible tariffs for GATT countries and other non-communist countries, whereas Column 2 contained our higher tariffs from the last Congressionally passed tariff (the Tariff Act of 1930, a.k.a. Smoot-Hawley). Section 5 of the 1951 Act directed that communist nations be moved to Column 2. Column 1 and 2 remain today, but Belarus, Cuba, North Korea, and Russia are the only countries in Column 2.

Throughout the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, the main legislative action in tariff policy was working to move countries from Column 2 to Column 1 as they shed communism. See our guide on Repealing China’s MFN status for more on Column 1 vs. Column 2, and expanding tariff preference programs.

Tariff Preference Programs in the GATT era have limited effect

In the 1960s, multinational enterprises concerned about ‘import substitution’ industrial policies in the non-Communist developing-world hatched a plan. They formed a group called the “Committee for Economic Development”, which argued that if poor countries protected the multinationals’ investment, they should be eligible for waivers of the negligible tariffs the U.S. had in Column 1, thus making them more attractive to further U.S. investment. In 1974, Congress passed the General System of Preferences (GSP) to do just that, which today offers unilateral tariff cuts to 119 countries, including Brazil.

Congress’ deployment of GSP was actually condemned at the time in a resolution by the Organization of American States due to the legislated criteria, which included not joining the OPEC oil cartel, thus excluding Ecuador and Venezuela.

Nonetheless, given our negligible Column 1 tariffs, further GSP tariff cuts – e.g., going from 2% to 0% – proved to have little effect on sourcing decisions. A Congressional Research Service report on GSP states that “Developing countries have expressed concern about the overall progressive erosion of preferential margins as a result of across-the-board tariff reductions” via the GATT.

Despite GSP’s sweeping coverage of 119 countries, only about 4% of U.S. merchandise imports are entered through GSP today. As most imports face 0% tariff, there is no incentive to even prepare the certificate of origin necessary to elect GSP status.

A final quick note about FTAs in the GATT era: between 1947 and 1989, the U.S. signed only one FTA, with Israel in 1980. In 1989, a U.S.-Canada FTA went into force, which in turn was subsumed into NAFTA in 1994. The North American FTAs were driven in large part by foreign investment concerns, particularly with regard to energy. Under NAFTA, the U.S. tariff on cars, at 2.5%, went to 0%, but this was not the reason for a rapid displacement of U.S. auto jobs to Mexico. The reason was the secured investment environment and lower wages in Mexico. Under the George W. Bush Administration, FTAs were entered into with 13 new countries, but these too have had little effect at their stated aims. (We’ll address a notable exception in CAFTA-DR below).

As of 2023, the United States has free trade agreements with twelve of the largest Western Hemisphere economies, and tariff preference programs covering the rest. These preferential tariff agreements and programs haven’t moved the needle, even with the support of dedicated government finance programs like the Inter-American Development Bank, established in 1959.

What makes the Americas Act different

Unlike everything tried in the last century, the Americas Act recognizes that using our giant marketplace to encouraging sourcing in the Americas only works if we first stop being a dumping ground to the whole world. So to that end, it tackles the two big problems at our ports: chronic nil-to-zero tariffs, and the de minimis loophole.

Americas’ Act tariff reform

Indeed, for generations, it’s been U.S. law – see 19 U.S.C. 2136(c) – to only expect tariff reciprocity with Canada, Europe, and Japan. (Thank heaven Henry Clay isn’t alive to see what we’ve done with our inheritance…)

Section 213 puts an end to this suicide. It states that

Emphasis added. “Schedule XX” refers to the U.S.’ Schedule of Concessions to the GATT, wherein the U.S. commits to an average 3.4% tariff to every WTO country. (See CPA guide to learn more about tariff reform, and about the GATT Art. XXVIII process).

There is little-to-no chance the countries of the world will come down close to our 3.4%. India has been steadily increasing its across the board tariffs in recent years with tremendous success. Raising our bound tariff rates to be ‘middle of the pack’ with WTO members would likely move us from 3.4% to something closer to 34%, a 10x, increase. But even going to something like Norway’s 20% would be a profound revenue event for the United States. Our China 301 tariffs apply to only about one-third of what China sends us in a given month, at an average rate of around 20%, and those limited tariffs have still helped shift sourcing out of China, while also providing a $50 billion per year windfall to the U.S. Treasury.

A policy of GATT Tariff Reciprocity as detailed in Section 213 is a win for America, and also a win for every country with whom we extend preferential tariff rates. It will supercharge sourcing to U.S. GSP beneficiaries, and even more so our FTA partners, as well as domestically.

CAFTA-DR’s “Yarn Forward” tariff rule illustrates ‘Near-Shoring’ success using high(er) tariffs

CAFTA-DR, our FTA with Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, as well as the Dominican Republic, is one ‘near-shoring’ story that did enjoy some success, in terms of apparel and textile products. We still have something like an average 14% tariff (low, but high by woeful U.S. standards) for clothing. And we thankfully excluded apparel from GSP tariff waivers. For these reasons, CAFTA-DR had an opening: apparel made in CAFTA-DR countries can be imported into the U.S. duty free if the apparel is made with American textiles (fabrics). This is known as the ‘Yarn Forward’ rule. Saving the average 14% was enough to lead many large clothing brands to make apparel in Central America, using U.S.-made textile inputs. Although that success is now largely being lost thanks to our de minimis loophole…

Americas Act attacks de minimis loophole

Little known outside trade circles a few years ago, the deluge of imports flooding in via de minimis – millions per day, a billion per year – without any scrutiny or revenue measures is high in Congress’ sights. (See CPA’s de minimis guide for more)

Senator Cassidy wants the Americas Act to tax the loophole, and then use the tax receipts to help shift sourcing from China to our own Hemisphere, a laudable goal. Senator Cassidy told the Miami Herald:

Between the increase of tariffs generally, and the taxing of de minimis shipments, the U.S. Treasury will be awash in new revenue, and our supply chains will certainly shift to countries with whom we have preferential tariffs arrangements. The bill envisages more trade finance tools to help the shift, but in the event our GATT/WTO tariffs do increase into the double digits, it’s hard to believe any more incentive would be needed.

Senator Cassidy deserves credit, especially as a member of the Senate Finance Committee, for being willing to take the bold and courageous steps actually necessary to create hemispheric supply chains. Members of Congress and Presidents have spent decades talking about Western Hemisphere integration, but Senator Cassidy is the first to introduce the necessary tariff and trade policies to get serious about it.

MADE IN AMERICA.

CPA is the leading national, bipartisan organization exclusively representing domestic producers and workers across many industries and sectors of the U.S. economy.

TRENDING

CPA: Liberty Steel Closures Highlight Urgent Need to Address Mexico’s Violations and Steel Import Surge

CPA Applauds Chairman Jason Smith’s Reappointment to Lead House Ways and Means Committee

Senator Blackburn and Ossoff’s De Minimis Bill is Seriously Flawed

JQI Dips Due to Declining Wages in Several Sectors as November Jobs Total Bounces Back from Low October Level

What Are Trump’s Plans For Solar in the Inflation Reduction Act?

The latest CPA news and updates, delivered every Friday.

WATCH: WE ARE CPA

Get the latest in CPA news, industry analysis, opinion, and updates from Team CPA.

CHECK OUT THE NEWSROOM ➔