by Jeff Ferry and David Morse

Jeff Ferry is chief economist and David Morse is tax policy director at the Coalition for a Prosperous America. They thank Mary Hollenbeck for her data collection and additional research for this article.

In this article, Ferry and Morse examine the advantages and disadvantages of pillar 1 of the OECD inclusive framework’s proposed tax reforms for the digital economy. This article originally appeared in Tax Notes titled, “Alternative Pillar 1 Formulas for International Fairness,” Tax Notes Federal, Dec. 13, 2021, pp. 1531-1536.

In October 2021, the OECD announced that it confirmed the support of 136 nations worldwide for a new global structure for corporate income tax known as the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS). The OECD plan contains two “Pillars.” Pillar One addresses the problem of companies generating revenue in jurisdictions where they pay little or no corporate tax. Pillar Two addresses the problem of companies shifting profits to low-tax tax havens. In this article, we focus on Pillar One.

Pillar One addresses tax challenges arising from the growing internationalization of the world economy and growing digitalization. Online retailer Amazon epitomizes the problem in the digital industry sector. Amazon sells online in dozens of national markets around the world, with a minimal presence in many of those markets. Current corporate taxation is based on residency transfer pricing, “arms-length” taxation principles. This means that corporations pay tax based on attributing profit to its source or origin. Online retailers like Amazon can do business in many markets without booking any corporate profits in those markets since the incorporated entity booking the revenue can be located in the U.S. or virtually anywhere else. Even if corporate revenue is booked in the local market, modern tech companies are often structured in such a way as to pay royalties for the intellectual property (IP) used in their business to a subsidiary in a low-tax tax haven. An online retailer in a major consumer market, such as a European nation, could book billions of dollars of revenue in the consumer market but then, by paying royalties to the IP-owning sister company in a tax haven, shows no profits in the relevant consumer market. Local brick-and-mortar retailers, and even many smaller, local online retailers, pay corporate taxes in each national market at or close to the headline tax rate, typically between 19% and 33%. They are at a considerable disadvantage competing against an international online retailer paying little or no tax in that national market or worldwide.

However, the problem is not limited to technology companies. Many non-technology companies are able to use tax strategies to minimize taxes in a national market. For example, in 2012, an investigation of global coffee shop retailer Starbucks by the U.K. House of Commons found that Starbucks paid close to zero corporate tax in the U.K. despite reporting to investors that the U.K. market was highly profitable. Starbucks used a set of tax maneuvers, all legal, to shift profits away from the U.K. to lower-tax jurisdictions. The tactics involved the creation of Starbucks subsidiaries in other countries owning Starbucks’ unique recipes and charging royalties to Starbucks U.K. for the use of them, thereby reducing the reported profits of Starbucks U.K. Starbucks U.K. would buy Starbucks coffee beans, purchased around the world by Starbucks Trading, headquartered in a low-tax Swiss canton. The beans never had to physically go through the canton, just the paper ownership. Then, Starbucks Manufacturing would receive the beans and roast them in the Netherlands. Each step looked to apply a 20% mark up.[1] But the coffee beans are not the only objects in a coffee cup sale. Napkins and cups and other ancillary costs could be similarly accounted for in manipulating the cost of goods sold.

Multinational pharmaceutical companies are another notable beneficiary of the current taxation methods. The OECD BEPS Inclusive Framework is expected to recapture hundreds of millions of dollars per year. But Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson are using the goodwill earned from vaccination manufacture to pressure Congress to protect them.[2] Pfizer’s participation is notable because previous reports indicated that Pfizer had been shifting profits generated by drugs developed in the U.S. and sold worldwide to tax havens in Ireland and elsewhere for over a decade.[3] Last year, Pfizer made a profit of $7.5 billion on $41.9 billion in revenue, on which it paid a global tax provision of just $736 million or 10%. Its cash tax payment to the federal government was just $371 million, equivalent to just 4.9% of its profits.

The Pillar One plan developed by the OECD in consultation with corporate and public sector representatives from many countries involves authorizing the collection of a portion of the profits linked to revenue generated in national markets. These profits are then reallocated to the market jurisdictions. The portion of profits that may be taxed this way is limited by multiple parameters, including notably the size of the company, the profitability of the company, and a 25% apportioning to be allocated to this new tax base.

The fundamental principle of linking corporate taxation to the national market where customers pay revenue is accepted by over 137 national governments, including the United States and virtually every other major economy. In the words of the OECD statement of October 8th, for purposes of the new Pillar One corporate tax, “Revenue will be sourced to the end market jurisdictions where goods or services are used or consumed.”[4]

As we have argued before, the only fair way to levy corporate profit, especially in developed countries, is to base all corporate taxation on profit linked to the sales generated in each jurisdiction. The current system is far too easy to manipulate. It is only becoming more so as intellectual property is involved in more businesses. Each year more businesses become aware of the potential to minimize taxes by clever, entirely legal tactics. Pillar 2 provides production-based tax carveouts that can drop the global minimum tax well below 15%, ensuring that tax competition between nations remains alive and well.

Even the relocation of intangible assets like intellectual property ownership in low-tax jurisdictions will not be entirely negated. Implementing Pillar Two will set a global minimum corporate tax rate of 15%. Still, the savings involved in the difference between many national rates, such as the U.S. at 21% and the 15% minimum, will still be significant enough to justify IP tax avoidance strategies for many multinational corporations.

Pillar One is a significant step towards a more rational global system of corporate taxation. However, one problem with the current version of the Pillar One system is it puts a considerable share of the burden on the U.S. because digital companies are the largest beneficiaries of the broken transfer pricing system. The current OECD formula is packed with exclusions and deductions to ensure that only a handful of huge multinationals are hit with the new Pillar One tax. These conditions end up protecting many non-U.S. corporations from Pillar 1 tax liability. This article looks at ways to modify those conditions to address concerns related to the Pillar 1 tax burden.

Pillar One includes only corporations with over 20 billion euros (about $23 billion) of revenue a year. That limits it to only the largest companies worldwide. Next, it excludes all financial and extractive (mining) businesses. Then, it applies only to companies earning profit at a rate of over 10% of sales in the relevant year. That first 10% of profit is termed “Routine Profit” by the OECD. The Pillar One tax is levied only on the profit above that 10%, which is termed “Residual Profit.” Finally, only a portion of that Residual Profit will be taxed. In the October 2021 OECD publication, that portion, known as the “Quantum,” is fixed at 25% of the Residual Profit.

This multi-stage formula ensures that the Pillar One tax begins by targeting the world’s largest and most profitable multinationals. The net will widen over time. According to the OECD, the revenue threshold should fall from 20 billion euros to 10 billion euros in Year Eight.[5]

To analyze the likely initial impact of Pillar One, we collected data on all companies in the Fortune Global 500 for 2020. We used actual data from financial statements to ensure we have accurate data for revenue, pretax profit, and other key variables. We found that a total of 76 companies met the October OECD Pillar One requirements. The split was even between U.S. and non-U.S. companies, with 38 American-headquartered companies qualifying for Pillar One and 38 qualifiers also headquartered outside the U.S.

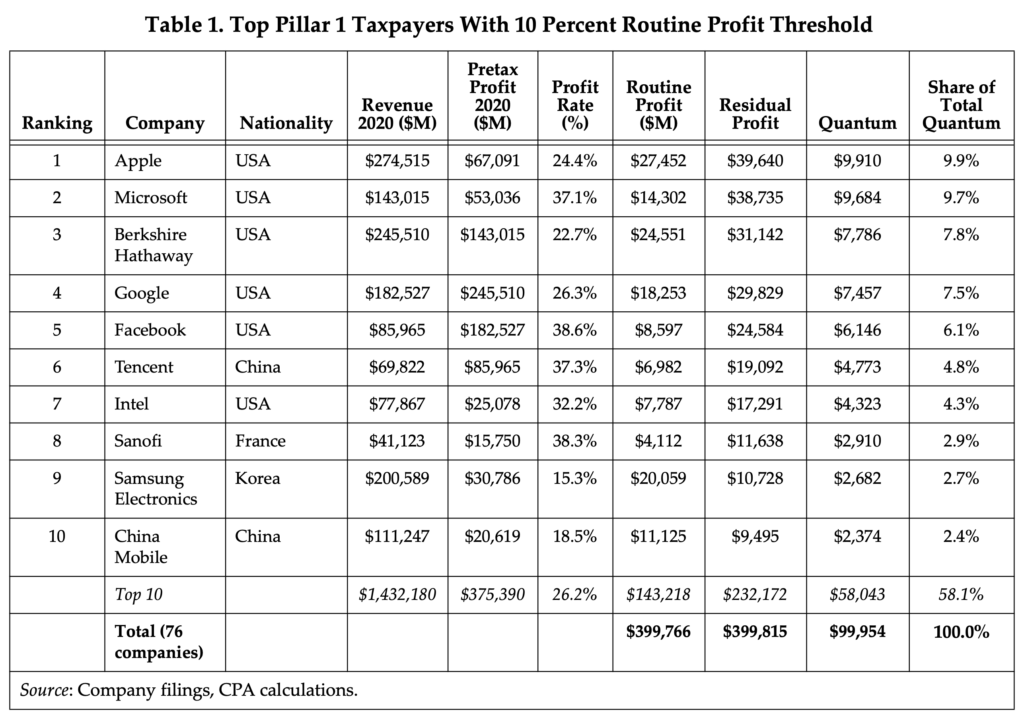

However, on a taxable revenue basis, the split is far less balanced. Under the OECD standards, these 76 qualifying companies had $399.8 billion of “Residual Profit” eligible for Pillar One taxation. With an OECD-set “Quantum” of 25%, that means a quarter of the total, or $99.95 billion of profit, would be taxed under Pillar One. U.S. companies account for 73.8% of that total. Such one-sidedness has raised specters of doubt towards the U.S. congressional agreement of Pillar One.[6] The 73.8% figure appears excessive when compared with the U.S. share of global GDP, which is just 24%. Actual tax liabilities will depend on how much revenue each company books in each foreign jurisdiction and how those jurisdictions choose to apply their national corporate tax to profits linked to that revenue. But our estimates provide a good starting point.

The reason why U.S. companies would be hit so hard by the current structure of Pillar One can be seen in Table 1. The largest companies that meet the Pillar One standard are U.S. “Big Tech” companies, and they are very highly profitable. The top five companies are our four largest tech giants plus Berkshire Hathaway, Warren Buffett’s huge conglomerate. Together these five account for $163.9 billion of the $399.8 billion in Residual Profit or 41% of the $99.95 billion total Quantum that would be taxed under the OECD formula.

The OECD formula uses one measure of profit, the ratio between pretax profit and total revenue (sales), as a key factor in determining eligibility for Pillar One tax. It has set a somewhat arbitrary threshold of 10% as “Routine Profit,” making only the excess over the 10%, labeled “Residual Profit” eligible for the tax. The aim of these artificial definitions and thresholds is to narrow down the number of eligible companies so as to make the Pillar One tax more politically palatable to many companies and their lobbyists who opposed these taxes.

Some experts have argued that Pillar 1 unfairly burdens U.S. companies because they tend to have higher profitability ratios than many non-U.S. companies.[7] They believe the U.S. suffers because it will not gain additional revenue in exchange for this potential agreement, and Pillar 1 cannot be salvaged as a result.

However, other experts focus on the revenue-based allocation key as the culprit that denies the developing nations their share of the tax. They argue Market countries are the true beneficiaries of the agreement and developing nations gain the crumbs.[8] Experts in this camp have no love for the monopolistic tendencies of the greatest tax avoiders, even if they are American companies in name.

The dissonant existence between these two arguments where the U.S. will both not benefit or benefit too much can be resolved by refocusing on the political construction of Pillar 1. The limitation of a 10% Routine threshold creates an imbalanced application and should be considered for review.

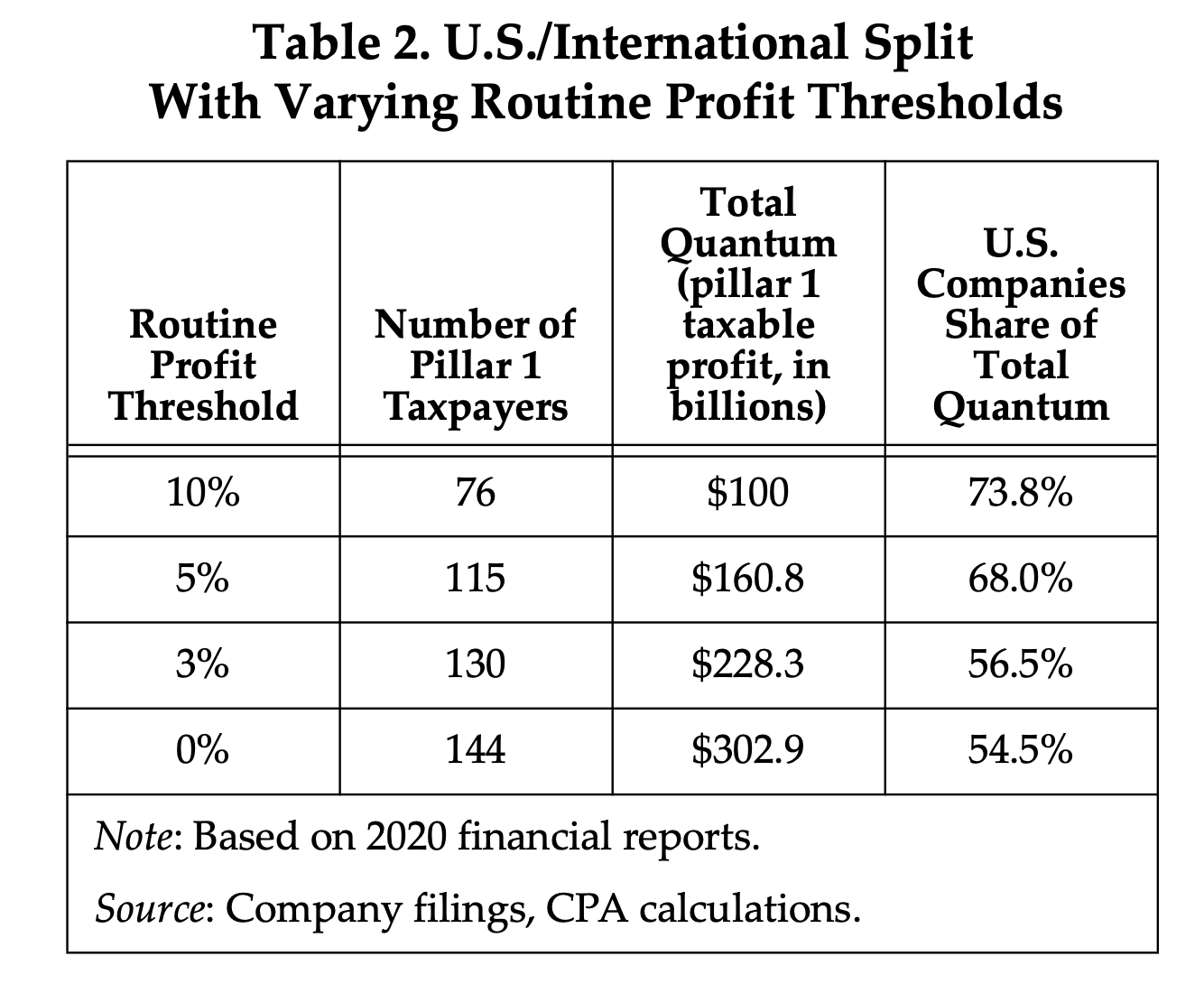

One way to broaden the net to resolve both complaints is to lower the Routine Profit threshold. In Table 2, we show comparisons as to how the tax would work with various levels of Routine Profit thresholds.

Lowering the threshold has three advantages: it increases the number of companies liable to pay Pillar One tax, it increases the dollar value of the Quantum of profit liable for the tax, and it increases the concentration of non-American companies liable for the tax.

It also eliminates some of the randomness that comes from an artificially chosen threshold. For example, Amazon is probably the company that has done most to drive the 136 nations to press for a new form of corporate taxation. Amazon’s large online sales in many nations, often accompanied by small payments of corporate tax in those nations, was a big contributor to the pressure for new forms of corporate taxation. Yet under the current OECD formula, Amazon would not be liable for Pillar One tax. The reason is that Amazon’s profit rate last year was just 6.3%, well below the 10% threshold set by the OECD.

In an effort to pull Amazon into the Pillar One net, some national governments pressed to tax Amazon’s two major divisions separately under a specialized rule known as segmentation. The Amazon retail business showed an operating profit of $9.4 billion with a profit rate of 2.7% last year, while the technology business, Amazon Web Services, booked an operating profit of $13.5 billion, for a profit rate of 29.7% last year. Ironically, Pillar One could lead to AWS paying tax in many foreign jurisdictions, even though it is Amazon’s retail business that has caused the most grievances in foreign markets.

In an effort to pull Amazon into the Pillar One net, some national governments pressed to tax Amazon’s two major divisions separately under a specialized rule known as segmentation. The Amazon retail business showed an operating profit of $9.4 billion with a profit rate of 2.7% last year, while the technology business, Amazon Web Services, booked an operating profit of $13.5 billion, for a profit rate of 29.7% last year. Ironically, Pillar One could lead to AWS paying tax in many foreign jurisdictions, even though it is Amazon’s retail business that has caused the most grievances in foreign markets.

Another example of the strange effects of a 10% threshold is that it excludes supermarket businesses. For example, U.S. supermarket chain Trader Joe’s, with over 500 locations, is owned by a German company, while Aldi, with over 2,000 US locations, is owned by another German company. Both are multibillion-dollar businesses. Yet neither one would be liable for Pillar One tax because supermarkets typically show a profit rate well under 10%, usually under 5%. (As privately owned businesses, neither of these supermarket chains publish profitability figures.)

Table 2 shows that as the rate of Routine Profit excluded from Pillar One tax liability declines, the tax net widens. With a 5% threshold for Routine Profit, based on our 2020 data, 115 companies would become liable for the tax (including Amazon), with a taxable Quantum of $160.8 billion. That’s 60% more taxable profit than in the 10% Routine Profit case. With a 3% Routine Profit threshold, 130 companies would be liable for the tax, with a taxable Quantum of $228.3 billion. Finally, a Routine Profit threshold of zero would make 144 companies liable for the tax, with a Quantum of $302.9 billion.

In the case of a zero Routine Profit threshold, U.S. companies would pay only 54.5% of the total tax. While recognizing the weight of the current U.S. digital footprint in the world economy, this more balanced approach resolves both sets of complaints. Also, as the OECD and many observers would like the system to broaden over time, a move now to a zero Routine Profit threshold would be a good early step in that direction.

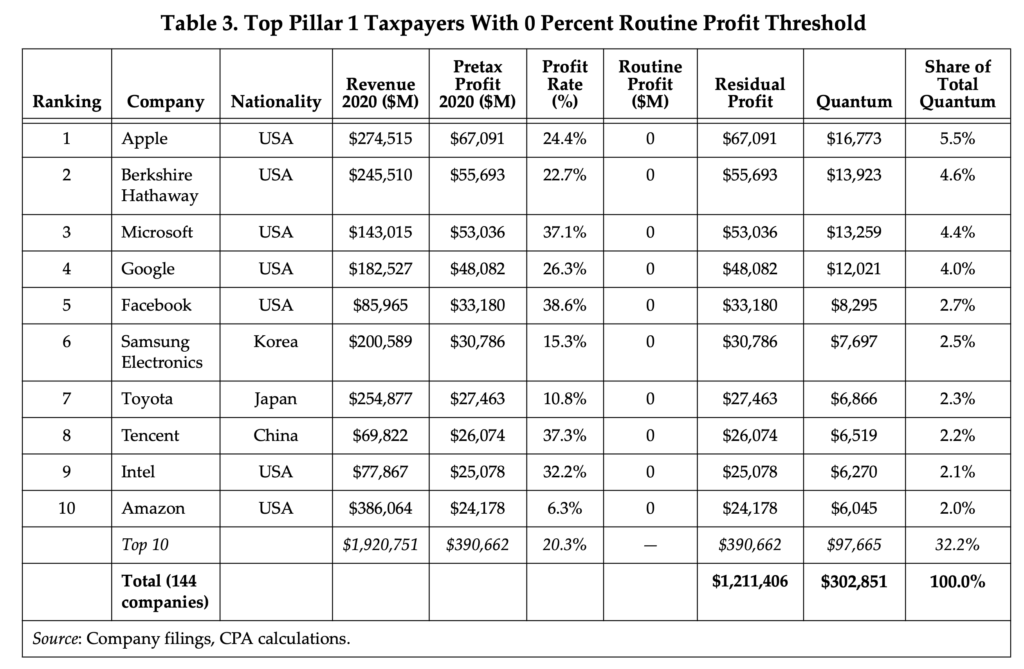

Table 3 shows the top Pillar One taxpayers with a zero Routine Profit threshold, i.e., when all pretax profit is included but then reduced by 75% to generate the 25% Quantum. Amazon now just makes it into the top ten because although its rate of profit is low, the absolute value of its profit, $24.2 billion last year, is very high. The U.S. still dominates the list, but by bringing more foreign companies into the list of taxpayers, foreign taxpayers at 82 now outnumber U.S. taxpayers at 62.

A broader net means a fairer distribution of the tax burden. It is also a bigger step towards universalizing a system of corporate tax based on the location of revenue and customers rather than the increasingly untenable origin of profit.

[1] Kleinbard, Ed. Through a Latte, Darkly: Starbucks’s Stateless Income Planning. Tax Notes, June 24, 2013, pp. 1515-1535

[2] Strasburg, Jenny and Cooper, Laura. Big Pharma Quietly Pushes Back on Global Tax Deal, Citing Covid-19 Role. WSJ. July 27, 2021

[3] Bergin, Tom and Drawbaugh, Kevin. How Pfizer has shifted U.S. profits overseas for years. Reuters. November 16, 2015.

[4] OECD, Statement on a Two-Pillar Solution to Address the Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalisation of the Economy, Attachment A, pg. 11, Oct. 8, 2021.

[5] Soong Johnston, Stephanie. Countries Advance Historic Global Tax Plan With New Details. 2021 TNTI 127-4, Jul, 6 2021.

[6] Lee, Frederic. GOP Senators Warn Against Skipping Treaty Process on Pillar 1. Tax Notes Int’l, Oct. 18, 2021, p. 349.

[7] Herzfeld, Mindy, Is the OECD Deal Good or Bad for the United States? Tax Notes Int’l, Oct. 25, 2021, p. 377

[8] Stiglitz, Joseph. Making the international corporate tax system work for all. The Progressive Post.

Alternative Pillar 1 Formulas for International Fairness

by Jeff Ferry and David Morse

Jeff Ferry is chief economist and David Morse is tax policy director at the Coalition for a Prosperous America. They thank Mary Hollenbeck for her data collection and additional research for this article.

In this article, Ferry and Morse examine the advantages and disadvantages of pillar 1 of the OECD inclusive framework’s proposed tax reforms for the digital economy. This article originally appeared in Tax Notes titled, “Alternative Pillar 1 Formulas for International Fairness,” Tax Notes Federal, Dec. 13, 2021, pp. 1531-1536.

In October 2021, the OECD announced that it confirmed the support of 136 nations worldwide for a new global structure for corporate income tax known as the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS). The OECD plan contains two “Pillars.” Pillar One addresses the problem of companies generating revenue in jurisdictions where they pay little or no corporate tax. Pillar Two addresses the problem of companies shifting profits to low-tax tax havens. In this article, we focus on Pillar One.

Pillar One addresses tax challenges arising from the growing internationalization of the world economy and growing digitalization. Online retailer Amazon epitomizes the problem in the digital industry sector. Amazon sells online in dozens of national markets around the world, with a minimal presence in many of those markets. Current corporate taxation is based on residency transfer pricing, “arms-length” taxation principles. This means that corporations pay tax based on attributing profit to its source or origin. Online retailers like Amazon can do business in many markets without booking any corporate profits in those markets since the incorporated entity booking the revenue can be located in the U.S. or virtually anywhere else. Even if corporate revenue is booked in the local market, modern tech companies are often structured in such a way as to pay royalties for the intellectual property (IP) used in their business to a subsidiary in a low-tax tax haven. An online retailer in a major consumer market, such as a European nation, could book billions of dollars of revenue in the consumer market but then, by paying royalties to the IP-owning sister company in a tax haven, shows no profits in the relevant consumer market. Local brick-and-mortar retailers, and even many smaller, local online retailers, pay corporate taxes in each national market at or close to the headline tax rate, typically between 19% and 33%. They are at a considerable disadvantage competing against an international online retailer paying little or no tax in that national market or worldwide.

However, the problem is not limited to technology companies. Many non-technology companies are able to use tax strategies to minimize taxes in a national market. For example, in 2012, an investigation of global coffee shop retailer Starbucks by the U.K. House of Commons found that Starbucks paid close to zero corporate tax in the U.K. despite reporting to investors that the U.K. market was highly profitable. Starbucks used a set of tax maneuvers, all legal, to shift profits away from the U.K. to lower-tax jurisdictions. The tactics involved the creation of Starbucks subsidiaries in other countries owning Starbucks’ unique recipes and charging royalties to Starbucks U.K. for the use of them, thereby reducing the reported profits of Starbucks U.K. Starbucks U.K. would buy Starbucks coffee beans, purchased around the world by Starbucks Trading, headquartered in a low-tax Swiss canton. The beans never had to physically go through the canton, just the paper ownership. Then, Starbucks Manufacturing would receive the beans and roast them in the Netherlands. Each step looked to apply a 20% mark up.[1] But the coffee beans are not the only objects in a coffee cup sale. Napkins and cups and other ancillary costs could be similarly accounted for in manipulating the cost of goods sold.

Multinational pharmaceutical companies are another notable beneficiary of the current taxation methods. The OECD BEPS Inclusive Framework is expected to recapture hundreds of millions of dollars per year. But Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson are using the goodwill earned from vaccination manufacture to pressure Congress to protect them.[2] Pfizer’s participation is notable because previous reports indicated that Pfizer had been shifting profits generated by drugs developed in the U.S. and sold worldwide to tax havens in Ireland and elsewhere for over a decade.[3] Last year, Pfizer made a profit of $7.5 billion on $41.9 billion in revenue, on which it paid a global tax provision of just $736 million or 10%. Its cash tax payment to the federal government was just $371 million, equivalent to just 4.9% of its profits.

The Pillar One plan developed by the OECD in consultation with corporate and public sector representatives from many countries involves authorizing the collection of a portion of the profits linked to revenue generated in national markets. These profits are then reallocated to the market jurisdictions. The portion of profits that may be taxed this way is limited by multiple parameters, including notably the size of the company, the profitability of the company, and a 25% apportioning to be allocated to this new tax base.

The fundamental principle of linking corporate taxation to the national market where customers pay revenue is accepted by over 137 national governments, including the United States and virtually every other major economy. In the words of the OECD statement of October 8th, for purposes of the new Pillar One corporate tax, “Revenue will be sourced to the end market jurisdictions where goods or services are used or consumed.”[4]

As we have argued before, the only fair way to levy corporate profit, especially in developed countries, is to base all corporate taxation on profit linked to the sales generated in each jurisdiction. The current system is far too easy to manipulate. It is only becoming more so as intellectual property is involved in more businesses. Each year more businesses become aware of the potential to minimize taxes by clever, entirely legal tactics. Pillar 2 provides production-based tax carveouts that can drop the global minimum tax well below 15%, ensuring that tax competition between nations remains alive and well.

Even the relocation of intangible assets like intellectual property ownership in low-tax jurisdictions will not be entirely negated. Implementing Pillar Two will set a global minimum corporate tax rate of 15%. Still, the savings involved in the difference between many national rates, such as the U.S. at 21% and the 15% minimum, will still be significant enough to justify IP tax avoidance strategies for many multinational corporations.

Pillar One is a significant step towards a more rational global system of corporate taxation. However, one problem with the current version of the Pillar One system is it puts a considerable share of the burden on the U.S. because digital companies are the largest beneficiaries of the broken transfer pricing system. The current OECD formula is packed with exclusions and deductions to ensure that only a handful of huge multinationals are hit with the new Pillar One tax. These conditions end up protecting many non-U.S. corporations from Pillar 1 tax liability. This article looks at ways to modify those conditions to address concerns related to the Pillar 1 tax burden.

Pillar One includes only corporations with over 20 billion euros (about $23 billion) of revenue a year. That limits it to only the largest companies worldwide. Next, it excludes all financial and extractive (mining) businesses. Then, it applies only to companies earning profit at a rate of over 10% of sales in the relevant year. That first 10% of profit is termed “Routine Profit” by the OECD. The Pillar One tax is levied only on the profit above that 10%, which is termed “Residual Profit.” Finally, only a portion of that Residual Profit will be taxed. In the October 2021 OECD publication, that portion, known as the “Quantum,” is fixed at 25% of the Residual Profit.

This multi-stage formula ensures that the Pillar One tax begins by targeting the world’s largest and most profitable multinationals. The net will widen over time. According to the OECD, the revenue threshold should fall from 20 billion euros to 10 billion euros in Year Eight.[5]

To analyze the likely initial impact of Pillar One, we collected data on all companies in the Fortune Global 500 for 2020. We used actual data from financial statements to ensure we have accurate data for revenue, pretax profit, and other key variables. We found that a total of 76 companies met the October OECD Pillar One requirements. The split was even between U.S. and non-U.S. companies, with 38 American-headquartered companies qualifying for Pillar One and 38 qualifiers also headquartered outside the U.S.

However, on a taxable revenue basis, the split is far less balanced. Under the OECD standards, these 76 qualifying companies had $399.8 billion of “Residual Profit” eligible for Pillar One taxation. With an OECD-set “Quantum” of 25%, that means a quarter of the total, or $99.95 billion of profit, would be taxed under Pillar One. U.S. companies account for 73.8% of that total. Such one-sidedness has raised specters of doubt towards the U.S. congressional agreement of Pillar One.[6] The 73.8% figure appears excessive when compared with the U.S. share of global GDP, which is just 24%. Actual tax liabilities will depend on how much revenue each company books in each foreign jurisdiction and how those jurisdictions choose to apply their national corporate tax to profits linked to that revenue. But our estimates provide a good starting point.

The reason why U.S. companies would be hit so hard by the current structure of Pillar One can be seen in Table 1. The largest companies that meet the Pillar One standard are U.S. “Big Tech” companies, and they are very highly profitable. The top five companies are our four largest tech giants plus Berkshire Hathaway, Warren Buffett’s huge conglomerate. Together these five account for $163.9 billion of the $399.8 billion in Residual Profit or 41% of the $99.95 billion total Quantum that would be taxed under the OECD formula.

The OECD formula uses one measure of profit, the ratio between pretax profit and total revenue (sales), as a key factor in determining eligibility for Pillar One tax. It has set a somewhat arbitrary threshold of 10% as “Routine Profit,” making only the excess over the 10%, labeled “Residual Profit” eligible for the tax. The aim of these artificial definitions and thresholds is to narrow down the number of eligible companies so as to make the Pillar One tax more politically palatable to many companies and their lobbyists who opposed these taxes.

Some experts have argued that Pillar 1 unfairly burdens U.S. companies because they tend to have higher profitability ratios than many non-U.S. companies.[7] They believe the U.S. suffers because it will not gain additional revenue in exchange for this potential agreement, and Pillar 1 cannot be salvaged as a result.

However, other experts focus on the revenue-based allocation key as the culprit that denies the developing nations their share of the tax. They argue Market countries are the true beneficiaries of the agreement and developing nations gain the crumbs.[8] Experts in this camp have no love for the monopolistic tendencies of the greatest tax avoiders, even if they are American companies in name.

The dissonant existence between these two arguments where the U.S. will both not benefit or benefit too much can be resolved by refocusing on the political construction of Pillar 1. The limitation of a 10% Routine threshold creates an imbalanced application and should be considered for review.

One way to broaden the net to resolve both complaints is to lower the Routine Profit threshold. In Table 2, we show comparisons as to how the tax would work with various levels of Routine Profit thresholds.

Lowering the threshold has three advantages: it increases the number of companies liable to pay Pillar One tax, it increases the dollar value of the Quantum of profit liable for the tax, and it increases the concentration of non-American companies liable for the tax.

It also eliminates some of the randomness that comes from an artificially chosen threshold. For example, Amazon is probably the company that has done most to drive the 136 nations to press for a new form of corporate taxation. Amazon’s large online sales in many nations, often accompanied by small payments of corporate tax in those nations, was a big contributor to the pressure for new forms of corporate taxation. Yet under the current OECD formula, Amazon would not be liable for Pillar One tax. The reason is that Amazon’s profit rate last year was just 6.3%, well below the 10% threshold set by the OECD.

Another example of the strange effects of a 10% threshold is that it excludes supermarket businesses. For example, U.S. supermarket chain Trader Joe’s, with over 500 locations, is owned by a German company, while Aldi, with over 2,000 US locations, is owned by another German company. Both are multibillion-dollar businesses. Yet neither one would be liable for Pillar One tax because supermarkets typically show a profit rate well under 10%, usually under 5%. (As privately owned businesses, neither of these supermarket chains publish profitability figures.)

Table 2 shows that as the rate of Routine Profit excluded from Pillar One tax liability declines, the tax net widens. With a 5% threshold for Routine Profit, based on our 2020 data, 115 companies would become liable for the tax (including Amazon), with a taxable Quantum of $160.8 billion. That’s 60% more taxable profit than in the 10% Routine Profit case. With a 3% Routine Profit threshold, 130 companies would be liable for the tax, with a taxable Quantum of $228.3 billion. Finally, a Routine Profit threshold of zero would make 144 companies liable for the tax, with a Quantum of $302.9 billion.

In the case of a zero Routine Profit threshold, U.S. companies would pay only 54.5% of the total tax. While recognizing the weight of the current U.S. digital footprint in the world economy, this more balanced approach resolves both sets of complaints. Also, as the OECD and many observers would like the system to broaden over time, a move now to a zero Routine Profit threshold would be a good early step in that direction.

Table 3 shows the top Pillar One taxpayers with a zero Routine Profit threshold, i.e., when all pretax profit is included but then reduced by 75% to generate the 25% Quantum. Amazon now just makes it into the top ten because although its rate of profit is low, the absolute value of its profit, $24.2 billion last year, is very high. The U.S. still dominates the list, but by bringing more foreign companies into the list of taxpayers, foreign taxpayers at 82 now outnumber U.S. taxpayers at 62.

A broader net means a fairer distribution of the tax burden. It is also a bigger step towards universalizing a system of corporate tax based on the location of revenue and customers rather than the increasingly untenable origin of profit.

[1] Kleinbard, Ed. Through a Latte, Darkly: Starbucks’s Stateless Income Planning. Tax Notes, June 24, 2013, pp. 1515-1535

[2] Strasburg, Jenny and Cooper, Laura. Big Pharma Quietly Pushes Back on Global Tax Deal, Citing Covid-19 Role. WSJ. July 27, 2021

[3] Bergin, Tom and Drawbaugh, Kevin. How Pfizer has shifted U.S. profits overseas for years. Reuters. November 16, 2015.

[4] OECD, Statement on a Two-Pillar Solution to Address the Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalisation of the Economy, Attachment A, pg. 11, Oct. 8, 2021.

[5] Soong Johnston, Stephanie. Countries Advance Historic Global Tax Plan With New Details. 2021 TNTI 127-4, Jul, 6 2021.

[6] Lee, Frederic. GOP Senators Warn Against Skipping Treaty Process on Pillar 1. Tax Notes Int’l, Oct. 18, 2021, p. 349.

[7] Herzfeld, Mindy, Is the OECD Deal Good or Bad for the United States? Tax Notes Int’l, Oct. 25, 2021, p. 377

[8] Stiglitz, Joseph. Making the international corporate tax system work for all. The Progressive Post.

MADE IN AMERICA.

CPA is the leading national, bipartisan organization exclusively representing domestic producers and workers across many industries and sectors of the U.S. economy.

TRENDING

CPA: Liberty Steel Closures Highlight Urgent Need to Address Mexico’s Violations and Steel Import Surge

CPA Applauds Chairman Jason Smith’s Reappointment to Lead House Ways and Means Committee

Senator Blackburn and Ossoff’s De Minimis Bill is Seriously Flawed

JQI Dips Due to Declining Wages in Several Sectors as November Jobs Total Bounces Back from Low October Level

What Are Trump’s Plans For Solar in the Inflation Reduction Act?

The latest CPA news and updates, delivered every Friday.

WATCH: WE ARE CPA

Get the latest in CPA news, industry analysis, opinion, and updates from Team CPA.

CHECK OUT THE NEWSROOM ➔