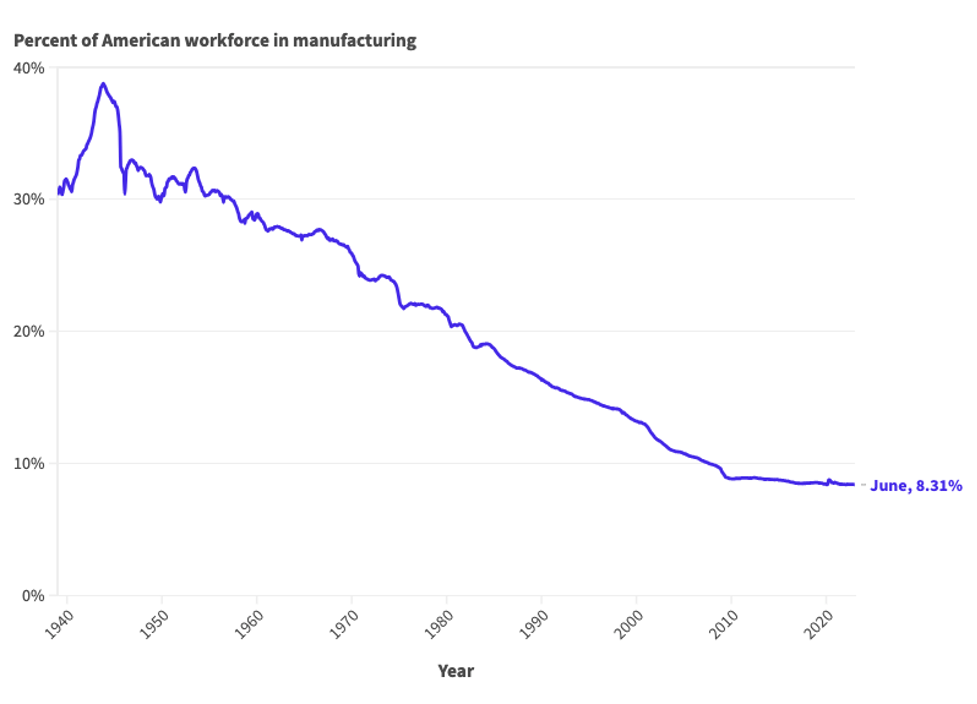

Manufacturing employment in the U.S. has hit its lowest share of the U.S. workforce since modern records began in 1939. At 8.3% of total American employment, it is at an all-time low. We are far from the days of the 1950s and 1960s when manufacturing made up 30% of the workforce, the U.S. economy grew by 2%-4% a year and family incomes rose steadily.

According to Bureau of Labor Statistics data, manufacturing employment was 12.989 million in June, up 7,000 from the previous month. It’s also up 170,000 from June the previous year. But services employment has been rising faster, with total nonfarm employment up by 3.8 million to 156.2 million over the past year.

Manufacturing jobs continue to be “good jobs” because they tend to pay well, offer benefits like health insurance, and generally involve steady work at 40 hours a week, with opportunities for overtime. Also, manufacturing has traditionally been a route to a middle-class lifestyle for those without a four-year college degree. Over 60% of U.S. adults do not have a four-year degree.

Fig 1: Mfg employment as share of total employment

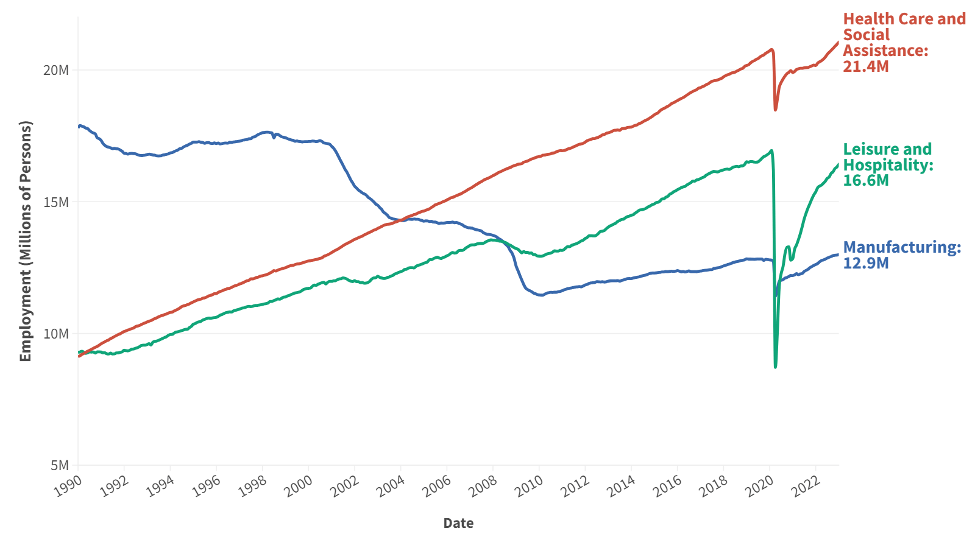

Figure 2 below shows how the composition of the U.S. workforce has changed over the past 30 years. In 2008 the leisure and hospitality sector surpassed the manufacturing sector in employment numbers. That was not good news for the workers in those industries. As Table 1 shows, the average leisure and hospitality worker earns 58.5% less than the average manufacturing worker. That’s a huge income reduction for someone who loses a manufacturing job and goes to work at a restaurant or hotel.

With the growth of U.S. spending on health care, the health care and social assistance sector has surpassed both manufacturing and leisure/hospitality in terms of employee numbers. This sector has slightly higher average weekly earnings than manufacturing. However, when average weekly hours are taken into account, health care workers earn on average 14.8% less than manufacturing workers.

There is another important consideration too. Manufacturing has been the primary engine of U.S. economic growth during the “American century” of extraordinary growth, 1870-1970, (Gordon, 2016) because of its ability to deliver steady productivity improvements which then bring about increases in income to workers and management alike. Workers have enjoyed a shrinking share of those productivity improvements since 1980 for a variety of reasons, including international competition from low-wage nations which have dragged U.S. worker incomes down. But at least manufacturing still offers productivity improvements, which can be shared among participants in the production process. Many health care activities are inherently personal services with much less opportunity for productivity improvement.

Fig 2: Health Care, Leisure/Hospitality have overtaken Manufacturing in employment totals

Table 1: Manufacturing pays higher weekly wages than other sectors.

| Sector | NAICS sector code | Total Employment (millions) | Average Hourly Wage | Average Weekly Earnings | Earnings discount to mfg earnings |

| Manufacturing | 31, 32, 33 | 12.99M | $32.38 | $1298.44 | 100 |

| Leisure/Hospitality | 71,72 | 16.58M | $21.21 | $538.73 | -58.5% |

| Health Care/Social Assistance | 62 | 21.35M | $33.14 | $1106.88 | -14.8% |

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics. All data for June 2023.

Bidenomics Begins to Rebuild the Manufacturing Workforce, But Is It Enough?

There is early evidence that the two major industrial policy support programs passed by the Biden administration, the Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS Act, could provide a substantial boost to manufacturing employment. Both of these programs use tax credits used to reduce corporate tax liability if companies invest in new plant and equipment on U.S. soil. The IRA covers renewable energy, electric vehicles and batteries. The CHIPS Act covers investment in semiconductors and related production. The combined government support will total close to $500 billion over ten years.

According to a study from Energy Innovation, the IRA is expected to create some 1.2 million new jobs by 2030, of which 365,000 should be manufacturing jobs. The Semiconductor Industry Association has said that the CHIPS Act should generate an additional 42,000 jobs at chip companies and an additional 102,000 “induced” jobs among suppliers to chip companies, for a total of 143,000 new manufacturing jobs.

Those are significant increases in employment for those sectors. But for the total manufacturing sector, an increase of 143,000 jobs represents just a 1.1% boost to manufacturing employment. The spending is concentrated on a handful of sectors and many of them are high-technology and highly labor efficient. Even in electric vehicles, which is relatively labor-intensive, the investment in EVs will be accompanied by a scaling down of traditional gasoline vehicles, leading to no change or even a reduction in total employment in the motor vehicle sector.

For a significant upturn in manufacturing employment, a broad-based policy program would be needed. It would have to address the one third of the manufacturing sector that is today taken by imports, according to CPA’s Domestic Market Share Index. It would also need to focus on training and apprenticeship.

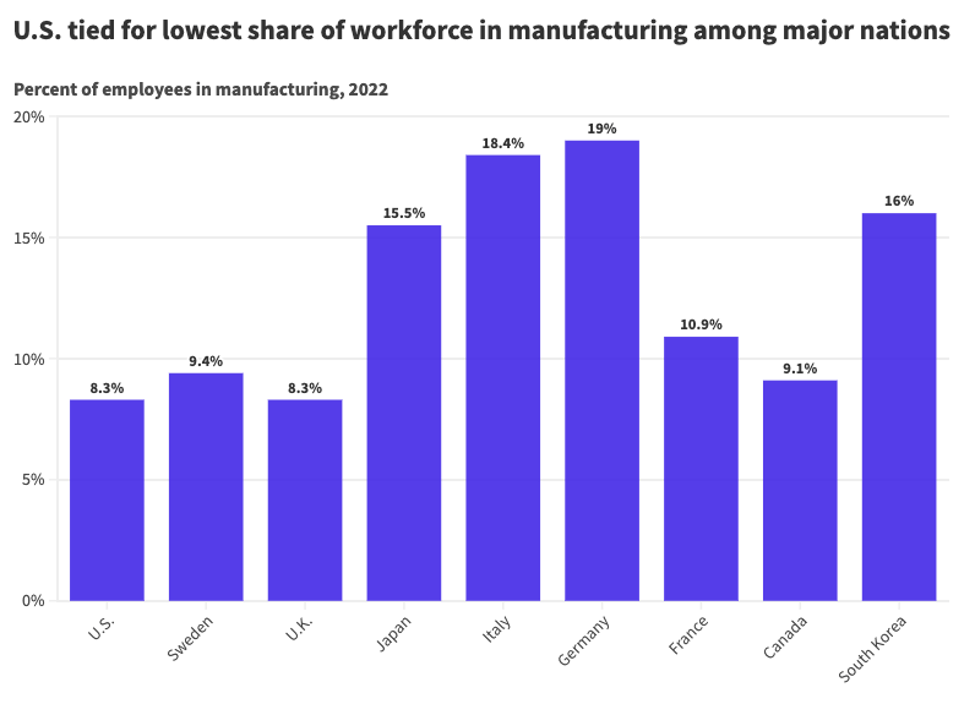

Figure 3 puts the U.S. manufacturing sector into international perspective. The U.S. has the lowest share of manufacturing employment, tied with the United Kingdom, of nine major advanced economies. This is an important factor in the sub-normal economic growth of both nations in the last thirty years.

Figure 3.

References

Robert Gordon, The Rise and Fall of American Growth, Princeton University Press, 2016.