Intel announced last week it will spend $20 billion building two new fabs in Arizona to take it into the foundry business, aiming to make chips for large, important customers like Apple, Microsoft or Qualcomm.

That’s good news, but it doesn’t solve the fundamental problem of US dependency on Asia for the manufacture of chips. Our analysis suggests the problem will get worse, not better, as more US chip design companies rely on Asian manufacturing. The fundamental driving force is the short-termism of the US chipmakers. This drives US tech companies out of manufacturing and global chip manufacturing into non-American locations. This financial analysis of the global chip industry shows how this dynamic works.

We compared the largest US-owned chip companies to the largest foreign-owned chip companies. We found that US chipmakers spent far less of their profit on capital spending last year and returned far more of their profit to shareholders than did foreign chipmakers.

The data shows that chipmakers in general are highly profitable companies. Table 1 shows that US chipmakers generated operating profit of 25% last year. Foreign chipmakers generated a similar return, 28%. These rates of profit are roughly double that of a typical industrial company. Microchips, or semiconductors to use the more formal name, have been highly profitable since the birth of the modern industry in the early 1980s. The profitability is due, firstly, to their enormous functionality. One chip less than one square inch can run a mobile smartphone or a laptop computer or an automotive entertainment system. The list of tasks such a processor chip can manage is truly amazing. For example, a recent smartphone processor from Qualcomm, the Snapdragon 768G, contains about 6 billion transistors. It can simultaneously manage 5G telecom reception, Wi-Fi reception, a phone display screen with fast-moving graphics in hundreds of colors, a camera up to 36 megapixels resolution, audio sounds, and more, all at the same time.

All that functionality allows chipmakers to charge premium prices for their products. According to one industry estimate, that Qualcomm Snapdragon might cost around $500. That’s roughly half the retail price of the typical consumer 5G smartphone built around it. The second reason chipmakers are highly profitable is volume. Chipmakers generally sell millions of each chip, so economies of scale allow for big profits.

The third reason for the strong profitability is less well-known but equally important. Chipmakers generally have very little competition. There are usually just two, sometimes three, chipmakers making a product for each product category. For example, the only competitor to Qualcomm’s Snapdragon is a chip made by Taiwanese chipmaker Mediatek. The dominant chips for the servers that power the Internet are made by Intel. Intel’s only serious competitor in the data center is AMD. And so it goes. When there are only a very small number of competitors, there is less competition and prices tend to be high.

Capital Investment vs. Returning Money to Shareholders

What do the chipmakers do with all those profits? Here there is a big difference between the US chipmakers and the foreign ones. US chipmakers tend to return their profits to shareholders. Foreign chipmakers opt instead for capital investment, investing back in their own businesses. Our data, covering 13 of the largest US chipmakers, shows that last year the US chipmakers generated total operating profit of $51.6 billion. Of that total, only $27.3 billion was reinvested in the form of capital expenditure. At the same time, $42.8 billion was returned to shareholders. In other words, the US chipmakers spent 57% more on returning money to shareholders than they reinvested in their own businesses.

The picture is reversed for foreign chipmakers. The foreign chipmakers in our sample invested $21 billion in capital spending while returning only just over half that total, or $11 billion, to their shareholders. Our foreign sample is smaller, including just five large foreign chipmakers, since several major foreign chipmakers, including Samsung and Sony, do not break out the financials for their chip business separately. Nevertheless, the comparison is striking. Of the $11 billion the foreign chipmakers returned to shareholders last year, fully $10.2 billion of it was in the form of dividends. Only $807 million was in the form of repurchasing their own stock.

In the US case, $19.5 billion went back to shareholders in the form of dividends. A larger sum, $23.3 billion, was returned via shareholder buybacks. Almost half of their profits went back to shareholders as buybacks. The sole reason for a company buying back its own shares is to boost its share price. By spending billions of dollars buying their own shares, the management teams of the US chipmakers are essentially saying: “we are more interested in raising our stock price than in investing in our own business.”

Outsiders often attribute the fixation on managing the short-term stock price to financial pressure from the investor community. That’s part of the story. The US stock market and US public company managers are focused on the short term. But typically, the short-term mindset is stronger among company management than in the investor community. Many professional fund managers are searching for companies they can invest in for the long term. Warren Buffett is well-known for saying his favorite holding period for a stock is “forever.” Ron Baron, one of Wall Street’s best-known mutual fund managers, explains his investment philosophy in his most recent quarterly newsletter this way: “…we have 10-year time horizons that we focus on…not on results in the next quarter…or even the next year.”

In contrast, the CEOs and senior executives of many tech companies are determinedly short-term. They want to keep their stock price on an upward trajectory for the three to five years they typically serve in their job. That will let them pick up a total compensation package in the millions (tens of millions for the CEO), and then move on to a bigger and better job. Since sales and economic cycles are inherently unpredictable, company leadership uses a steady stream of share buybacks to put some steady upward lift into their stock price. Another popular strategy to boost a share price is to sell off assets. This reduces the cost base and frees up cash—which can be used for more share buybacks.

Let’s compare the largest US chipmaker, Intel, with the largest foreign chipmaker, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp, known as TSMC. Last year, TSMC generated $48 billion in revenue and $20.2 billion in operating profit. It reinvested $18 billion in capital investment, a huge sum of money which will go into upgrading its network of chip manufacturing facilities. It returned $9.2 billion to shareholders in the form of dividends. TSMC is focused on maintaining its position at the front of the pack in chip manufacturing. That’s why it invests so heavily. It is also a mainstay of the Taiwanese economy and the Taiwanese government keeps a watchful eye on it. It pays a reasonable dividend at the normal rate for a tech company, no more and no less.

Intel is an integrated chipmaker and the world’s largest chipmaker. It both designs and manufactures chips. Last year, it pulled in operating profit of $23.9 billion on revenue of $77.9 billion. Despite its broader portfolio than TSMC, its capital spending budget was lower, at $14.5 billion last year. It returned $5.6 billion to shareholders in the form of dividends…and an astonishing $14.2 billion in the form of share buybacks! This is a staggering sum, over $1 billion a month. Why is one of the world’s leading technology companies, the architect of a huge part of the personal computer revolution and the Internet revolution, returning huge amounts of cash to shareholders? Many investors simply shrug helplessly at this fact—and with good reason. They’d much rather the company of Gordon Moore and Andy Grove spent money on great new ideas for new products.

A few weeks ago Intel made an important management change when it brought in veteran technologist Pat Gelsinger as CEO. We can only hope that it will do less financial engineering and more investment in its business.

Table 1: US vs. Foreign Chipmakers: Key Financial Parameters

| US Chipmakers |

Foreign Chipmakers | Intel (USA) |

TSMC (Taiwan) |

|

| Millions of Dollars | ||||

| Total Revenue | $ 207,289 | $ 83,401 | $ 77,867 | $ 47,632 |

| Operating Profit | $ 51,567 | $ 23,573 | $ 23,876 | $ 20,158 |

| Operating Margin | 24.9% | 28.3% | 30.7% | 42.3% |

| Total Capital Expenditures | $ 27,330 | $ 21,004 | $ 14,453 | $ 18,040 |

| Capex as % of Op. Profit | 53.0% | 89.1% | 60.5% | 89.5% |

| Dividends Paid | $ 19,503 | $ 10,204 | $ 5,568 | $ 9,222 |

| Repurchase of Stock | $ 23,299 | $ 807 | $ 14,229 | $ – |

| Total Cash Returned to Shareholders | $ 42,802 | $ 11,011 | $ 19,797 | $ 9,222 |

| Cash Returned as % of Op. Profit | 83.0% | 46.7% | 82.9% | 45.8% |

Source: Company Reports, Seeking Alpha; All data for Fiscal Year 2020

US chipmakers include: Intel, Broadcom, Qualcomm, Micron, TI, Nvidia, AMD, ADI, Microchip, On Semi, Skyworks, Qorvo and Marvell

Foreign chipmakers include: TSMC, ST Micro, Infineon, NXP Semi, and Renesas.

Asset-Light Fabless Chipmaking

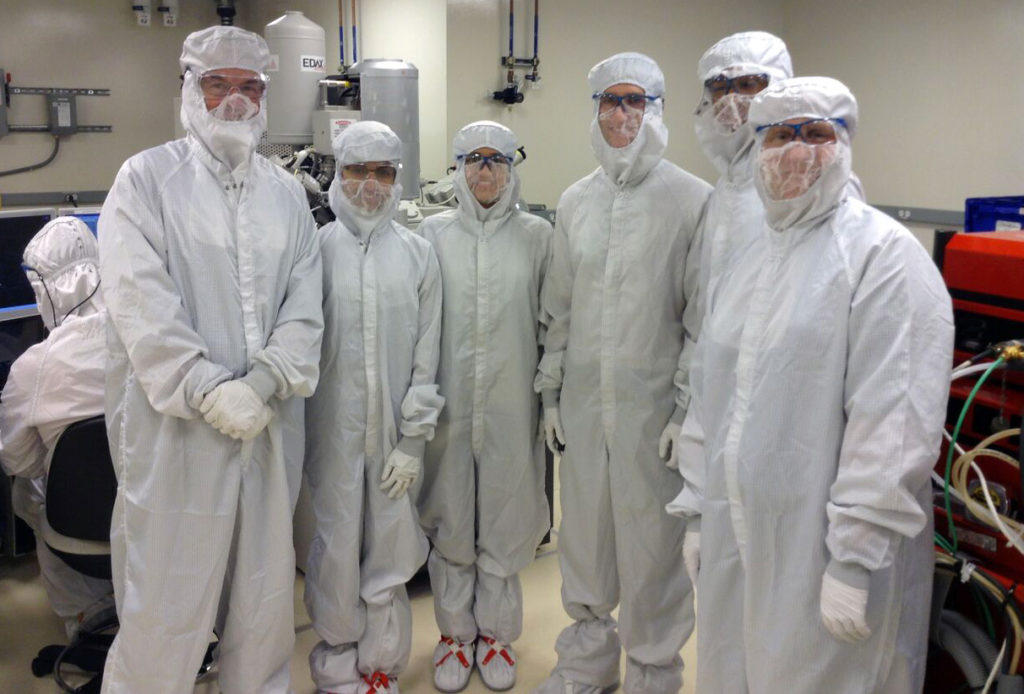

For US chipmakers, the trend for the last 20 years has been to get out of manufacturing and focus instead on the asset-light business of chip design, to become what is known in the industry as a “fabless chipmaker.” Almost every chipmaking company founded in the US this century has been fabless.

There has been a global bifurcation in the chip industry. The US concentrates on asset-light companies dedicated to making a small number of people rich in a short time. Foreign companies saw a complementary opportunity and leapt in. They began manufacturing the chips that US companies don’t want to make. So we have a division of labor where foreign chipmakers focus on the manufacturing side, generating healthy, moderate levels of wealth for a large number of people, including manufacturing workers and the many workers and companies that support them. In the 1980s, Taiwanese government officials saw that chip manufacturing could produce wealth on a national scale, actually making a material difference for a significant number of that nation’s 23 million people. South Korea, Singapore, and Israel made the same calculation and also supported chip manufacturing in their countries.

If you speak to people at those foreign chipmaking companies, they’ll tell you they’re proud to be part of companies that contribute substantially to their nation’s wealth and economic fabric. They’re building companies they hope will last for 20, 50, or even 100 years. If you speak to executives in Silicon Valley, they are proud of the products they’ve created, and they believe technology is “changing the world.” But many of them would not be surprised if their company gets acquired, or disappears, in the next five years. They have little or no interest in the state of the rest of the USA, or even the rest of California.

If we don’t change the economic time horizons in this country, we will increasingly become a nation focused on asset-light companies that make fewer and fewer people richer and richer, and ignore the 90% of the population that can’t share in producing leading-edge technologies.

Solving this problem will require measures to make corporate success dependent on performance over 10 or 20 years, not the 3 to 5 years of today. Another solution could be to ban or tax heavily share buybacks. We need more companies with the goal of being an industry leader for the next century, not just until the current crop of stock options vest.

Working closely with my former boss, the founder and CEO of a successful Silicon Valley chipmaker, I’ve come to believe there are three principles for a successful tech startup: first, choose to do something that is really hard, even or especially if others believe it’s impossible; second, when you do finally figure out how to do it, make sure you are the best in the world at it; third, when you bring your product to market, try to make sure there are very few other competitors in that specific product category. Zero other competitors is the best number.

One company that has met all three of those objectives is Taiwan’s TSMC. TSMC is making chips with 3 nanometer transistors. That’s really hard. Nobody else is doing it today. And it’s the best in the world at it. The result is that TSMC is the company with the highest profit margin of all 18 companies in my sample. Last year its operating profit margin was 42%. That’s right. TSMC makes more money per dollar of sales than any asset-light fabless chipmaker.

The Taiwanese government of the 1980s made a better investment than any US venture capital firm. Now that’s some shrewd government capitalism.