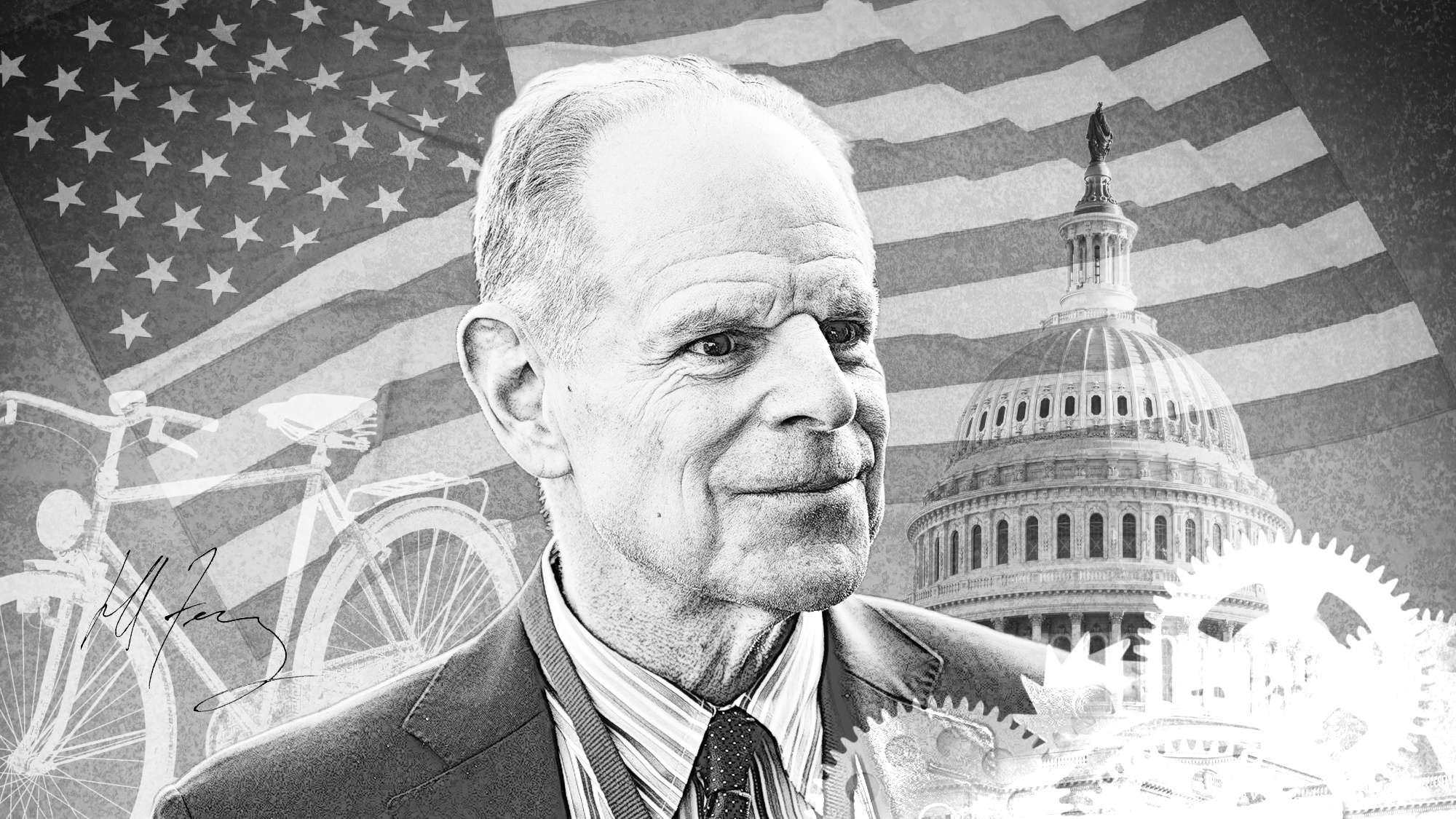

By Jason Cooper (CPA Research Assistant), Jeff Ferry (CPA Research Director), Michael Stumo (CEO of CPA)

Introduction

Trade in many fruit and vegetables has been disastrous for US agriculture and American farmers over the last two decades, following ratification of free trade agreements, notably those with Mexico (NAFTA), Central America (CAFTA), and Chile. In many cases, soaring levels of imports have been accompanied by little or no increase in exports. A detailed study by the nonpartisan Congressional Research Service published last year found that “the United States has gone from being a net exporter of fresh and processed fruits and vegetables in the early 1970s to being a net importer of fruits and vegetables today.”[1] The study attributed the rise in net imports to a number of factors including lower American tariffs than those of other nations, non-tariff barriers erected by other nations, government-subsidized production, and exchange rate fluctuations.

U.S. Fruit and Vegetable Trade (Excluding Nuts), 1990-2015

Source: US International Trade Commission via Congressional Research Service

Perhaps the best example of the failure of free trade agreements (FTAs) to benefit US producers is in avocados. In the last 34 years, as avocados became an increasingly fashionable vegetable, US consumption skyrocketed by 368%. Yet US production actually fell by 34% while imports took an 85% share of the US avocado market. Other shockingly poor results of trade under FTAs include the domestic lime industry, which has been virtually wiped out. US producers of cucumbers, grapes, and tangerines have also seen significant loss of domestic market share.

Here’s a summary of our results, followed by a detailed look at each individual product.

|

Product |

Pre-FTA Import Penetration (%) |

Import Penetration 2015 (%) |

Pre-FTA Trade Balance (000s of Tons) |

Trade Balance 2015 (000s of Tons) |

|

Avocados |

0% |

85% |

49 |

-1,894 |

|

Bell Peppers |

16% |

57% |

-56 |

-1,929 |

|

Cucumbers |

25% |

74% |

-130 |

-1,744 |

|

Grapes |

14% |

49% |

229 |

-347 |

|

Limes |

43% |

100% |

-34 |

-965 |

|

Pineapples |

44% |

92% |

-139 |

-2,241 |

|

Tangerines |

7% |

28% |

6 |

-374 |

|

Tomatoes |

26% |

53% |

-558 |

-3,243 |

Avocados

America once produced enough avocados to satisfy internal consumption, and even ran a small trade surplus in the product. However that was before NAFTA. Since the 1994 implementation of NAFTA, Mexican production exploded and substantially relied upon US consumers to buy their excess. US production fell by 34% since 1981. Domestic production of avocados was surpassed by imports in 2005.

|

Avocados |

US Production (000s of Tons) |

US Consumption (000s of Tons) |

Import Penetration (% of Domestic) |

Trade Balance (000s of Tons) |

|

1981 |

528 |

479 |

0% |

49 |

|

2015 |

347 |

2240 |

85% |

-1,894 |

|

Change from 1981 |

-34% |

+368% |

+85 |

-1943 |

|

Major 2015 Importers, in dollars: Mexico ($1524M), Peru ($83M) |

||||

Bell Peppers

As late as 1989, over 90% of bell peppers consumed in the USA were produced in the USA. However in 1990 imports spiked up to over a third, while from the early 1990s onwards American bell pepper production remained static, surpassed by foreign imports in 2015. While bell pepper production has not seen serious declines, it has remained constant even as domestic consumption ramped up 62%.

|

Bell Peppers |

US Production (000s of Tons) |

US Consumption (000s of Tons) |

Import Penetration (% of Domestic) |

Trade Balance (000s of Tons) |

|

Key Years |

||||

|

1970 (oldest data) |

387 |

444 |

16% |

-56 |

|

1996 (peak production) |

1664 |

2176 |

30% |

-512 |

|

2015 (current) |

1648 |

3577 |

57% |

-1,929 |

|

Change from 1996 |

-1% |

+64% |

+27 |

-1417 |

|

Major 2015 Importers, in dollars: Mexico ($852M), Canada ($276M), Netherlands ($44M) |

||||

Cucumbers

Cucumber production grew slowly but steadily through the 1970s and 1980s, but imports grew faster. By the 1990s domestic production peaked at 1183 thousand tons, before entering decline and are now barely half that. This happened even though consumption grew from 1879k to 2417k during the same period. Mexico accounted for over 2+ billion in imports, and Canada another 400+ million.

|

Cucumbers |

US Production (000s of Tons) |

US Consumption (000s of Tons) |

Import Penetration (% of Domestic) |

Trade Balance (000s of Tons) |

|

Key Years |

||||

|

1970 (oldest data) |

448 |

578 |

25% |

-130 |

|

1999 (peak production) |

1183 |

1879 |

40% |

-697 |

|

2015 (current) |

673 |

2417 |

74% |

-1,744 |

|

Change from 1999 |

-43% |

+29% |

+34 |

-1047 |

|

Major 2015 Importers, in dollars: Mexico ($2,132M), Canada ($429M) |

||||

Grapes

Unlike some of the other industries listed, US grape production has continued to see growth in production. However US production has not matched increased consumption. The US has gone from being a net exporter of 229 thousand tons in 1981, to a net importer of 347 tons in 2015, thanks predominantly to imports from Chile, though Mexico, Peru, and Argentina contribute as well.

|

Grapes |

US Production (000s of Tons) |

US Consumption (000s of Tons) |

Import Penetration (% of Domestic) |

Trade Balance (000s of Tons) |

|

Key Years |

||||

|

1981 |

1138 |

909 |

14% |

229 |

|

2015 |

2106 |

2453 |

49% |

-347 |

|

Change from 1981 |

+85% |

+170% |

+35 |

-576 |

|

Major 2015 Importers, in dollars: Chile ($827M), Mexico ($336M), Peru ($204M), Argentina ($59M) |

||||

Limes

US lime consumption has increased tenfold from 1981 to 2015. However the American industry, which once shipped 62,000 tons of limes, now produces none at all. While trade figures lump the more successful lemons with limes, most of America’s citrus imports now come from Mexico, followed by Chile, both FTA partners.

|

Limes |

US Production (000s of Tons) |

US Consumption (000s of Tons) |

Import Penetration (% of Domestic) |

Trade Balance (000s of Tons) |

|

Key Years |

||||

|

1981 |

62 |

96 |

43% |

-34 |

|

1992 |

94 |

261 |

58% |

-86 |

|

2015 |

0 |

965 |

101% |

-965 |

|

Change from 1992 |

-100% |

+270% |

+43 |

-879 |

|

Major 2015 Importers, in dollars: Mexico ($319M) and Chile ($42M) {for Lemons and Limes} |

||||

Pineapples

US production of pineapples peaked at 292,000 tons in 1989, and current figures put it as at around a quarter less. However that production is dwarfed by the 362% rise in pineapple consumption to 2.2 million tons. Rather than increasing US production, consumer demand has been fed by foreign production. Imports have come largely from nations with whom we have FTAs or preferential trade arrangements, such as Costa Rica and Mexico.

|

Pineapples |

US Production (000s of Tons) |

US Consumption (000s of Tons) |

Import Penetration (% of Domestic) |

Trade Balance (000s of Tons) |

|

Key Years |

||||

|

1980 |

202 |

341 |

44% |

-139 |

|

1989 |

290 |

485 |

45% |

-195 |

|

2015 |

175 |

2241 |

92% |

-2,241 |

|

Change from 1989 |

-40% |

+362% |

+56 |

-2046 |

|

Major 2015 Importers, in dollars: Costa Rica ($518M), Thailand ($230M), Philippines ($135M), Indonesia ($83M), Mexico ($45M) |

||||

Tomatoes

American tomato production peaked in 2002, and has since fallen by nearly a quarter, even as consumption continued to rise. In 2010 imports exceeded domestic exports for the first time. Tomato imports are dominated by imports from Mexico, which consumes little of its own harvest. Mexican production is targeted at American consumers and recently surpassed American production.

|

Tomatoes |

US Production (000s of Tons) |

US Consumption (000s of Tons) |

Import Penetration (% of Domestic) |

Trade Balance (000s of Tons) |

|

Key Years |

||||

|

1970 |

1933 |

2491 |

26% |

-558 |

|

2002 |

4289 |

5852 |

32% |

-1,563 |

|

2015 |

3343 |

6585 |

53% |

-3,243 |

|

Change from 2002 |

-23% |

+13% |

+19 |

-1680 |

|

Major 2015 Importers, in dollars: Mexico ($1691M), Canada ($270M) |

||||

Tangerines

Tangerine production has risen substantially, but the industry has gone from a net exporter to a net importer. China is the world’s largest producer of tangerines.

|

Tangerines |

US Production (000s of Tons) |

US Consumption (000s of Tons) |

Import Penetration (% of Domestic) |

Trade Balance (000s of Tons) |

|

Key Years |

||||

|

1981 |

453 |

447 |

7% |

6 |

|

2015 |

1296 |

1670 |

28% |

-374 |

|

Change from 1981 |

+186% |

+274% |

+21 |

-382 |

Trade Drivers

Overall the picture is no better. In the 1970s, before the era of free trade agreements, the US ran a surplus in fruits and vegetables. As of 2015, the trade figures were $6.3 billion in exports compared to $17.6 billion in imports, for a deficit of $11.3 billion. FTA nations in the Americas account for roughly three quarters of imports.

Much of the trade imbalance is rooted in America’s unilateral disarmament on trade. The global average tariff for fruits and vegetables is more than 50%. In developing nations, more than 80% of tariffs can be 25% or higher. In Japan and Europe, some 60% are in the 5% to 25% range. In the US, nearly 60% of fruit and vegetable tariffs are less than 5%.

The explanation goes beyond tariffs to include subsidies. European nations subsidize their fruit and vegetable producers, unlike the US, where our farm legislation has historically lacked assistance for specialty crops. Developing nations often have government-funded programs to help foster their industries. Phytosanitary barriers are used to restrict various US exports to South Korea and potato exports to Mexico.

The US International Trade Commission has investigated many nations for exporting to the US at prices below fair market value. Dumping petitions include includes fresh tomatoes (Canada, Mexico), frozen raspberries (Chile), apple juice concentrate (China), frozen orange juice (Brazil), lemon juice (Argentina, Mexico), fresh garlic (China), preserved mushrooms (China, Chile, India, Indonesia), canned pineapple (Thailand), table grapes (Chile, Mexico), and tart cherry juice (Germany, former Yugoslavia). Many of those petitions were fortunately decided in favor of US domestic producers leading to higher tariffs, but the fact remains that such tactics were used in the first place.

The fruit and vegetable trade picture mirrors that of US agriculture and manufacturing. Trade agreements were sold as benefitting exports with the implicit conclusion that American industry would benefit. But liberalized trade harmed our trade balance in these crops and diminished the economic health of America producers. If political and industry leaders are interested in recapturing American fruit and vegetable production to satisfy our growing consumer demand, they need to rethink whether low import tariffs and low domestic industry support achieve that goal.

Bibliography

USDA ERS Yearbook Tables. (17, January 13). Retrieved May 26, 2017, from https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/fruit-and-tree-nut-data/yearbook-tables/

USDA ERS Yearbook Tables. (17, April 6). Retrieved May 26, 2017, from https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/vegetables-and-pulses-data/yearbook-tables/

FAOSTAT. Retrieved May 26, 2017, from http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC/visualize

Johnson, R. (2016, December 1). The US Trade Situation for Fruit and Vegetable Products. Retrieved May 26, 2017, from http://prosperousamer.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/RL34468.pdf

[1] Johnson, R. (2016, December 1). The US Trade Situation for Fruit and Vegetable Products. Retrieved May 26, 2017, from http://prosperousamer.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/RL34468.pdf, pg. 2.