Editors note. Interesting map. Incorrect conclusion that the GOP caucus is or would have been leading on trade intervention, because they are not.

On Friday, Beijing announced new tariffs on $60 billion in U.S. goods — prompting new U.S. threats to ratchet up tariffs on Chinese exports to the United States. These are just the latest volleys in the trade war sparked by the Trump administration’s announcement to put tariffs on some $200 billion in Chinese exports.

[ John Seungmin Kuk, Deborah Seligsohn and Jiakun Jack Zhang | August 7, 2018 | Washington Post]

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (Ky.) and a few other Republicans in Congress have publicly criticized President Trump’s trade war with China, but most Republican lawmakers have not broken ranks with the administration. This is puzzling, when China appears to be targeting key Republican-held districts with its list of retaliatory tariffs.

Our research suggests that Republican attitudes on trade have been evolving — long before Trump’s China-bashing presidential campaign. We believe that Capitol Hill’s silence on free trade isn’t simply because Republicans are cowed by Trump or reluctant to alienate his supporters.

Republicans used to be reliable supporters of free trade

Congressional Republicans overwhelmingly supported the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1993, while the majority of Democrats were opposed. GOP support was also critical for the extension of permanent normal trade relations (PNTR) to China in 2000, a decision few congressional Democratssupported.

But rising import competition, specifically from China, shifted Republican attitudes on trade. Trump adviser Peter Navarro pointed to this growing “schism” between registered Republicans and the party leadership on trade in a 2016 interview with Politico. The Trump administration isn’t leading the GOP’s turn from free trade. It’s following an existing trend.

Here’s what changed

China’s entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001 helped boost global trade and benefited the U.S. economy in the aggregate, but it also resulted in import competition that hit certain U.S. industries and workers very hard.

The “China shock” analysis by David Autor, David Dorn and Gordon Hanson shows the effect of surging imports on specific segments of the economy. Communities with a higher concentration of lost manufacturing jobs experienced reduced lifetime earnings, higher rates of substance abuse, more broken families, falling property values, a shrinking tax base and growing demand for government transfers.

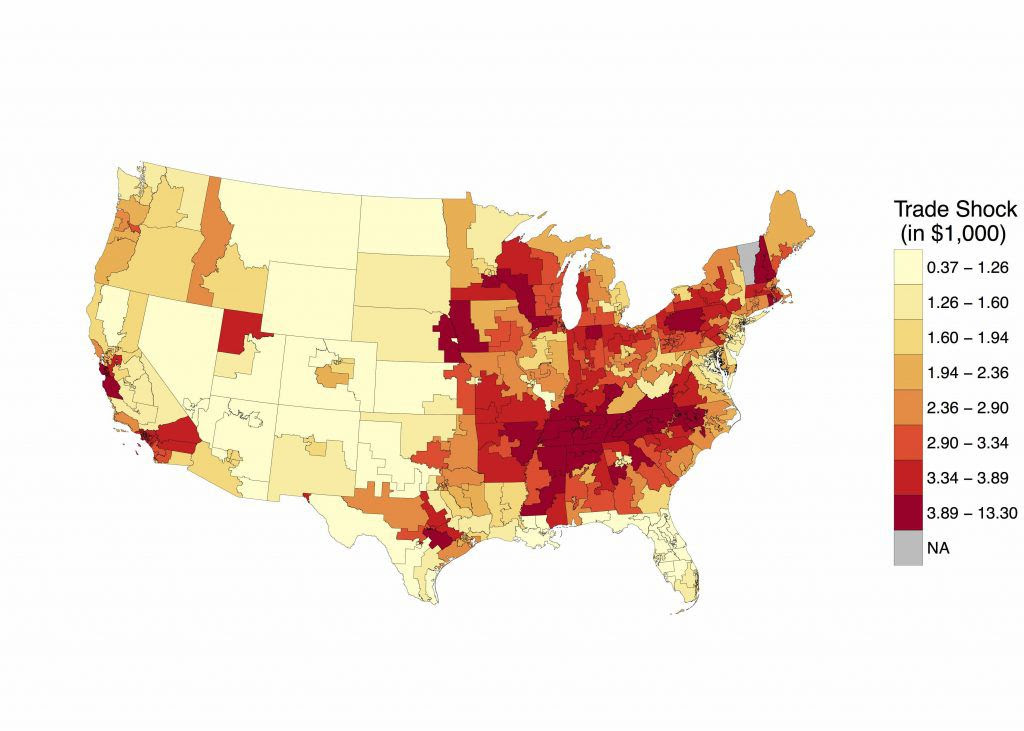

We used the China shock data on import competition per worker and mapped it by congressional district. The figure below shows the uneven impact across the country — the districts affected most are represented by both Republicans (e.g., the 9th District in North Carolina, on the southern border of the state) and Democrats (e.g., the 20th District in California, a coastal area south of San Jose).

Mapping the political geography of the China shock. We look at the change in Chinese import exposure per worker from 2000 to 2007 by congressional districts, where one unit of the measure is equivalent to $1,000 per worker. A value of 3.89 (shown in deep red, for example) means the value of Chinese imports between 2000 and 2007 increased by $3,890 per worker.

Mapping the political geography of the China shock. We look at the change in Chinese import exposure per worker from 2000 to 2007 by congressional districts, where one unit of the measure is equivalent to $1,000 per worker. A value of 3.89 (shown in deep red, for example) means the value of Chinese imports between 2000 and 2007 increased by $3,890 per worker. Data: Feigenbaum and Hall (2015)

Figure: Kuk, Seligsohn and Zhang (2018)

We examined how U.S. representatives communicated with their constituents about trade between 2005 and 2010, using a data set of all of their press releases. We used text analysis on China and trade discussions, and examined the way legislators addressed these two topics using sentiment analysis. This allowed us to evaluate whether legislators were more likely to use positive or negative words when discussing these topics if their district was more exposed to the China shock.

Our results suggest that import competition did not affect congressional discourse about free trade, but it did have a significant effect on the discussion of China, particularly in the context of economic competition. Representatives did not simply respond to rising import competition by becoming more protectionist in their trade policy preferences, as other scholars have suggested. Instead, they strategically adjusted their political messaging about China, focusing on Chinese cheating rather than the more general negative effects of trade to specific communities and income groups.

Free trade has a constituency in the United States. China does not.

The shift in rhetoric is more pronounced among Republicans. Republican legislators from districts that saw less impact from import competition did not talk much about China, and their statements were not systematically negative when they did.

But Republicans representing high-trade-shock districts sent out press releases with more negative statements on China — which read a lot like Democratic complaints about economic competition. These Republicans were more likely to blame China — not trade policy in general — for the negative externalities of import competition.

We argue that this difference in how the two parties communicate to voters about China reflects the fact that they start with very different baselines on trade. Democrats have long been skeptical of free trade, while Republicans for decades have embraced the doctrine of neoliberalism and opposed trade-adjustment assistance.

The redistributive impact of the China shock is not fundamentally different from previous waves of trade liberalization. But it happened at greater scale and over a shorter period. While Democrats were free to discuss China as part of a larger set of challenges brought by globalization, Republicans were under pressure from their leadership to toe the line on a trade-liberalizing agenda.

Scapegoating China for the negative externalities of trade was convenient and let Republican legislators respond to voter concerns while continuing to support their party’s position on free trade. Blaming China helped some secure reelection (incumbents in more exposed districts were not less likely to be reelected) without having to face the difficult problem of how to compensate the losers of globalization with stronger social protection. Once China was granted PNTR in 2000, removing an annual debate in Congress on whether the United States would extend normal trade rights to China, bashing China had few political costs since it did not jeopardize the bilateral economic relationship.

Trump inherited the GOP’s anti-China economic nationalism

This shift in rhetoric among Republican lawmakers predates Trump’s hostility toward China and helped create the current bipartisan consensus around anti-China economic nationalism. It also contributed to the illusion of solid Republican support for free trade at the national level in the face of rising economic competition.

As a result, we would suggest that even if the GOP leadership and major Republican donors were not ready for Trump’s trade war with China, rank-and-file congressional representatives had already sowed the seeds of economic nationalism among their constituents. On this issue, Trump seems to be following the Republican caucus rather than the other way around.