Editor’s note: A good piece on why trade deficits and offshoring are stupid and a recipe for national decline.

Offshoring by American companies has destroyed our manufacturing base and our capacity to develop new products and processes. It’s time for a national industrial policy.

[Sridhar Kota and Tom Mahoney | November 15, 2019 | WSJ]

In 1987, as the Reagan administration was nearing its end, the economists Stephen S. Cohen and John Zysman issued a prophetic warning: “If high-tech is to sustain a scale of activity sufficient to matter to the prosperity of our economy…America must control the production of those high-tech products it invents and designs.” Production, they continued, is “where the lion’s share of the value added is realized.”

Amid the offshoring frenzy that began in the late 1980s, this was heterodox thinking. In many quarters, it still is. Even as trade tensions with China have deepened, many U.S. political and economic leaders continue to believe that offshoring is not only profitable but also sound national economic strategy. Manufacturing in China is cheaper, quicker and more flexible, they argue. With China’s networks of suppliers, engineers and production experts growing larger and more sophisticated, many believe that locating production there is a better bet in terms of quality and efficiency. Instead of manufacturing domestically, the thinking goes, U.S. firms should focus on higher-value work: “innovate here, manufacture there.”

Today many Americans are rightly questioning this perspective. From the White House to Congress, from union halls to university laboratories, there is a growing recognition that we can no longer afford the outsourcing paradigm. Once manufacturing departs from a country’s shores, engineering and production know-how leave as well, and innovation ultimately follows. It’s become increasingly clear that “manufacture there” now also means “innovate there.”

What’s the solution? It’s time for the U.S. to adopt an industrial policy for the century ahead—not a throwback to old ideas of state planning but a program for helping Americans to compete with foreign manufacturers and maintain our ever more precarious edge in innovation.

Consider the results of the original offshoring craze of the 1960s, which centered on consumer electronics. The development of modern transistors, the establishment of standardized shipping containers and the creation of inexpensive assembly lines in East Asia cut costs for consumers and created huge markets for televisions and radios; it also catalyzed the Asian manufacturing miracle. Though American federal research investments in the decades that followed enabled the invention of game-changing technologies such as the magnetic storage drive, the lithium-ion battery and the liquid crystal display, the country had, by then, already let go of consumer electronics manufacturing. Asia dominated.

Since the turn of the millennium, the offshoring trend has accelerated, thanks to China’s entry into the World Trade Organization and major investments in workforce and production capacity by other Asian nations. U.S.-based companies began to contract out both design and product-development work. A 2015 study by the consulting firms Strategy& and PwC found that U.S. companies across sectors have been moving R&D to China to be closer to production, suppliers and engineering talent—not just to reap lower costs and more dynamic markets. An estimated 50% of overseas-backed R&D centers in China have been established by U.S. companies.

Innovation in manufacturing gravitates to where the factories are. American manufacturers have learned that the applied research and engineering necessary to introduce new products, enhance existing designs and improve production processes are best done near the factories themselves. As more engineering and design work has shifted to China, many U.S. companies have a diminished capability to perform those tasks here.

Manufacturing matters—especially for a high-tech economy. While it’s still possible to argue that the offshoring of parts, assembly and final production has worked well for multinational companies focused on quarterly earnings, it is increasingly clear that offshoring has devastated the small and medium-size manufacturers that make up the nation’s supply chains and geographically diverse industrial clusters. While the share of such companies in the total population of U.S. manufacturers has risen, their absolute numbers have dropped by nearly 100,000 since the 1990s and by 40,000 just in the last decade. Numbers have even fallen in relatively high-technology industries such as computers, electronics, electrical equipment and machinery.

The loss of America’s industrial commons—the ecosystem of engineering skills, production know-how and comprehensive supply chains—has not just devastated industrial areas. It has also undermined a core responsibility of government: providing for national defense. Recent Pentagon analyses of the defense industrial base have identified specific risks to weapons production, including fragile domestic suppliers, dependence on imports, counterfeit parts and material shortages. Meanwhile, despite tariffs, manufacturing imports continue to set records, especially in advanced technology products. Dependence on imports has virtually eliminated the nation’s ability to manufacture large flat-screen displays, smartphones, many advanced materials and packaged semiconductors. The U.S. now lacks the capacity to manufacture many next-generation and emerging technologies.

This is to say nothing of the human suffering and sociopolitical upheaval that have resulted from the hollowing out of entire regional economies. Once vibrant communities in the so-called Rust Belt have lost population and income as large factories and their many supporting suppliers have closed. The shuttering last March of the GM plant in Lordstown, Ohio—resulting in the loss of some 1,400 high-paying manufacturing jobs—is just the latest example. It joins a list that includes most of the long-established furniture industry in North Carolina, large steel mills in places like Bethlehem, Penn., and Weirton, W.Va., and the machine tool industry that once clustered around Cincinnati. Real wages across the country have been stagnant for decades, and though the causes are debatable, the loss of manufacturing jobs and the dramatic decline in manufacturing productivity growth have certainly played major roles.

In terms of long-term competitiveness, the biggest strategic consequence of this profound decline in American manufacturing might be the loss of our ability to innovate—that is, to translate inventions into production. We have lost much of our capacity to physically build what results from our world-leading investments in research and development. A study of 150 production-related hardware startups that emerged from research at MIT found that most of them scaled up production offshore to get access to production capabilities, suppliers and lead customers. As for foreign multinationals, many participate in federally funded university research centers and then use what they learn in their factories abroad. LG, Sharp and Auo, for example, were partners in the flexible display research center at Arizona State University funded by the U.S. Army, but they do not manufacture displays here.

The slow destruction of the U.S. industrial ecosystem is a clear case of market failure, and the government has an important role to play in remedying it. Thanks to continued federal funding in the sciences, the U.S. is still the best in the world in groundbreaking scientific discoveries and inventions. But the federal government must do more than invest in basic research; it must also fill the innovation deficit by creating a new infrastructure for R&D in engineering and manufacturing.

In too many industries, translational R&D capability has been lost, or at least seriously downsized, and the U.S. has lost its leadership position.

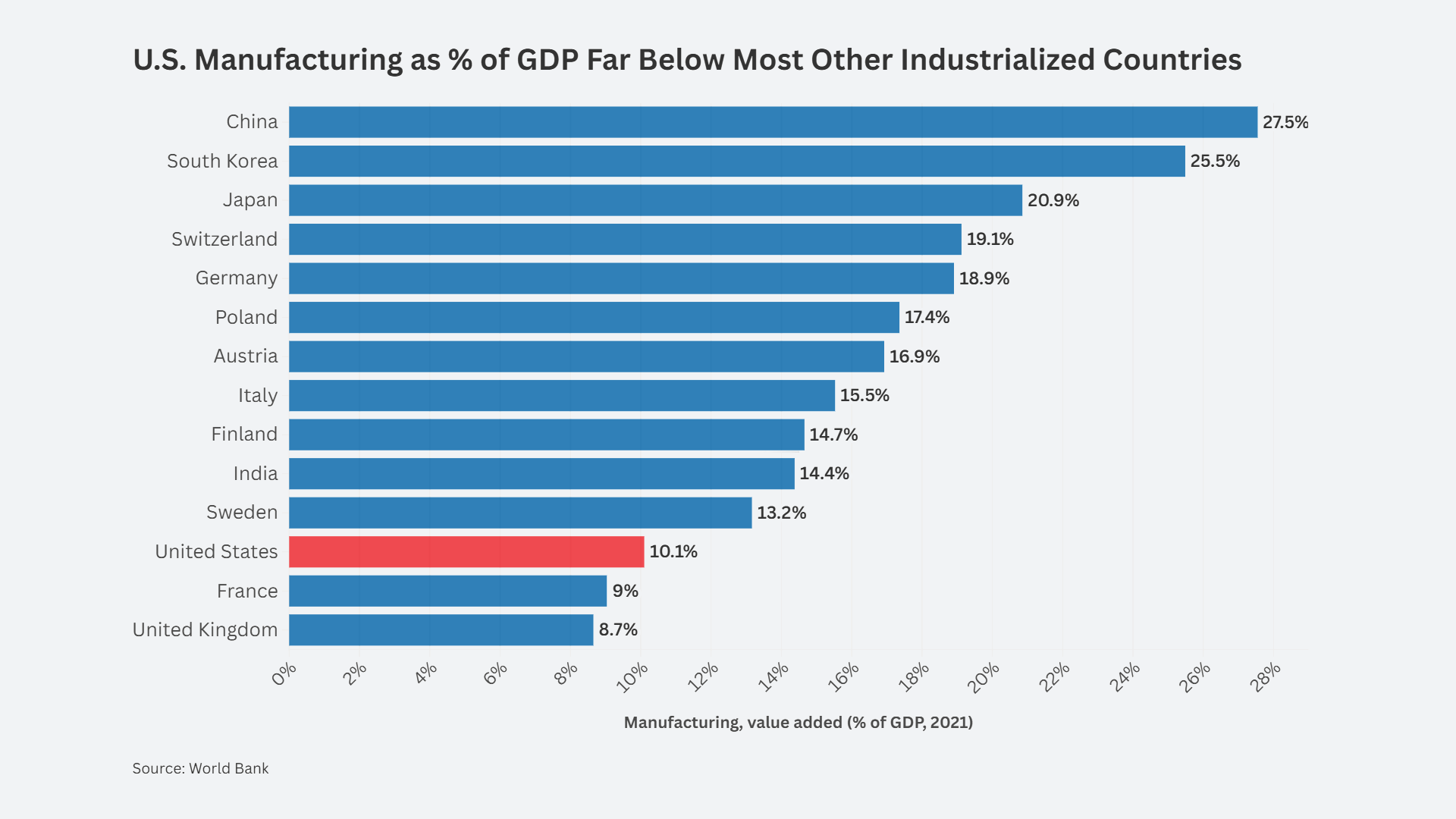

The American government invests about $150 billion annually in science and technology, significantly more than other advanced industrial nations. Yet relatively little of this is devoted to the translational R&D in engineering and manufacturing needed to turn basic research results into successful commercial products. Germany, Japan and South Korea spend 3 to 6 times as much as the U.S. on industrial and production technologies. These three advanced nations have high wages and strict regulations, and their energy costs and levels of automation are higher than in the U.S. Even so, they have maintained strong manufacturing sectors and weathered China’s rise far better than the U.S.

Historically, American companies have performed this essential translational research, but in the past two decades of cost cutting to maximize quarterly earnings, corporate R&D labs have been reduced or eliminated. Corporate R&D labs at GE, IBM, Xerox, AT&T and other industrial giants invented new products and production processes, ranging from semiconductors and lasers to MRI machines and industrial robots. In too many industries, this translational R&D capability has been lost, or at least seriously downsized, and the U.S. has lost its leadership position.

Aerospace is the main counter example, where the U.S. continues to lead in advanced technology. It is the last major industry that has maintained a strong trade surplus. Not surprisingly, it is also more dependent on government customers—mostly the Department of Defense—and the beneficiary of substantial government R&D investments in basic and translational research. Though few would call it such, this amounts to a successful industrial policy to support an industry deemed critical to national defense. It’s an example that needs to be replicated.

Unless something is done, the weak U.S. industrial commons will continue to create incentives for American companies to manufacture offshore, innovate offshore and weaken national competitiveness. A strategic and coordinated national effort is needed that moves beyond tax and trade policy, which, so far at least, has not resulted in an American manufacturing resurgence.

This national effort—call it Industrial Policy 2.0—should focus on ensuring that hardware innovations are manufactured in this country. The idea is not to recover lost industries but to rebuild lost capabilities. The U.S. needs to leverage its dominance in science and technology to create future industries, to provide us with first-mover advantages and reclaim American leadership in manufacturing.

The first step would be to create a new federal agency responsible for the health of U.S. manufacturing. A number of agencies currently have manufacturing-related programs, but there is little or no coordination or strategy. Defense alone cannot solve this challenge because defense procurement needs are dwarfed by commercial markets, and defense-specific technologies may have few commercial applications.

A new agency is needed to signal new priorities. This National Manufacturing Foundation, as it could be called, would be a cabinet-level agency focused on rebuilding America’s industrial commons and translating our scientific knowledge into new products and processes. What policies might it promote?

• To maximize the wealth and jobs created from our national R&D investments, the results must be manufactured in the U.S. Any licensee of federally funded research results should be required to manufacture at least 75% of the value added in this country, with no exceptions and no waivers.

• An additional 5% of the federal science and technology budget should be invested in engineering and manufacturing R&D and process technologies. This includes creating translational research centers as innovation hubs around the country. Affiliated with major research universities and institutions, these centers would take promising basic research results and perform the translational R&D necessary to demonstrate the viability of large-scale commercial production.

• Developing hardware typically requires more resources and time than developing software. Public-private partnerships could provide the needed patient capital. State-level programs in Massachusetts, Georgia and other states already provide encouraging examples. The South Carolina Research Authority, for example, provides grants, loans and direct investments to a portfolio of companies, roughly 40% of which are manufacturers. Leveraging defense procurement and other federal spending would help too, as would the targeted use of Small Business Administration loans.

• Restoring innovation in domestic manufacturing will require much greater investments in human capital. The country needs significantly more graduate fellowships in engineering for qualified domestic students and many more 4-year engineering technology programs that focus on application and implementation rather than concepts and theory. American multinationals need to do their part by revamping internship and apprenticeship programs to fill the skills gap.

Industrial Policy 2.0 would not be the industrial policy discussed and often criticized in past decades. It would not pick winners and losers but would keep other countries from taking advantage of our winners; it would make sure that the U.S., not its economic rivals, benefits from American know-how. The goal would be to maximize innovation in hardware technologies and, in doing so, to create high-value products, well-paying jobs, national wealth and national security.

Such steps are essential to generating a strong return on the U.S. taxpayer’s enormous investments in science and technology. For too long Americans have suffered from the self-inflicted wound of hollowing out our industrial capacity. Other countries have moved quickly to take our place. It’s time for the U.S. to act.

Read the original article here.