Editor’s note: More mainstream writing in favor of industrial strategy. While the article wrongly criticizes the tariff intervention against China, it rightly states that the US should have an industrial strategy. Side note: tariffs are part of industrial strategy, and often cheaper because you can protect industries without subsidizing them.

Washington’s focus on ending Beijing’s subsidies is illogical and self-defeating.

[Gabriel Wildau | November 16, 2019 | Bloomberg]

China hawks are chastising President Donald Trump’s “phase one” trade deal because it focuses on increasing U.S exports while ignoring Beijing’s subsidies for favored industries. Instead of seeking to coerce China into abandoning policies that both sides agree benefit its economy, the U.S. should seek to emulate them.

In one typical critique, experts at the Peterson Institute, a Washington think tank, lamented that Trump hasn’t explained “how his deal would tackle the Chinese subsidies that were the impetus for launching this trade war in the first place.” That’s a view shared by many in Washington. Though Trump himself often appears more concerned about bilateral deficits, it’s worth asking whether the concern over subsidies actually makes sense.

Until recently, mainstream economists and policymakers largely dismissed state-led industrial policy — a form of government intervention in the free market — as wasteful and ineffective. Government bureaucrats, the argument went, lack the ability to effectively pick winners among companies or industry sectors. The task is better left to venture capitalists and stock market investors. Moreover, a politicized process of distributing public money is inherently susceptible to rent-seeking and corruption.

If this view is correct, then the U.S. has little to fear from Chinese industrial policy. Let Beijing waste public resources and distort capital allocation, while Washington sticks to its free-market principles, confident that this approach will produce a more competitive economy in the long run.

Today, however, appraisals of China’s trade and commercial practices implicitly grant that its industrial policies are effective. And many economists now agree that this approach can succeed in promoting national leadership in strategic industries. If so, then it’s unreasonable to demand that China abandon policies to promote indigenous development — especially when the U.S. government is actively blocking key Chinese companies like Huawei Technologies Co. from accessing American-made technology.

At this point, it’s worth distinguishing between two categories of industrial policy. Traditional objections focused on commodity industries such as steel, where government support mainly leads to expanded production, without much innovation or value-chain advancement. Subsidies that mainly spur excess capacity produce negative-sum outcomes, and efforts to reduce such aid is worthwhile. China recently withdrew from an international forum designed to cooperatively manage excess steel capacity, claiming it has already achieved significant cuts, though the U.S. and Europe disagree.

In the current trade war, however, U.S. complaints mainly focus on a second category of subsidies: those targeted at “emerging and foundational” technology. Made in China 2025 is the most high-profile of Beijing’s initiatives to help its national champions win market share in strategic industries.

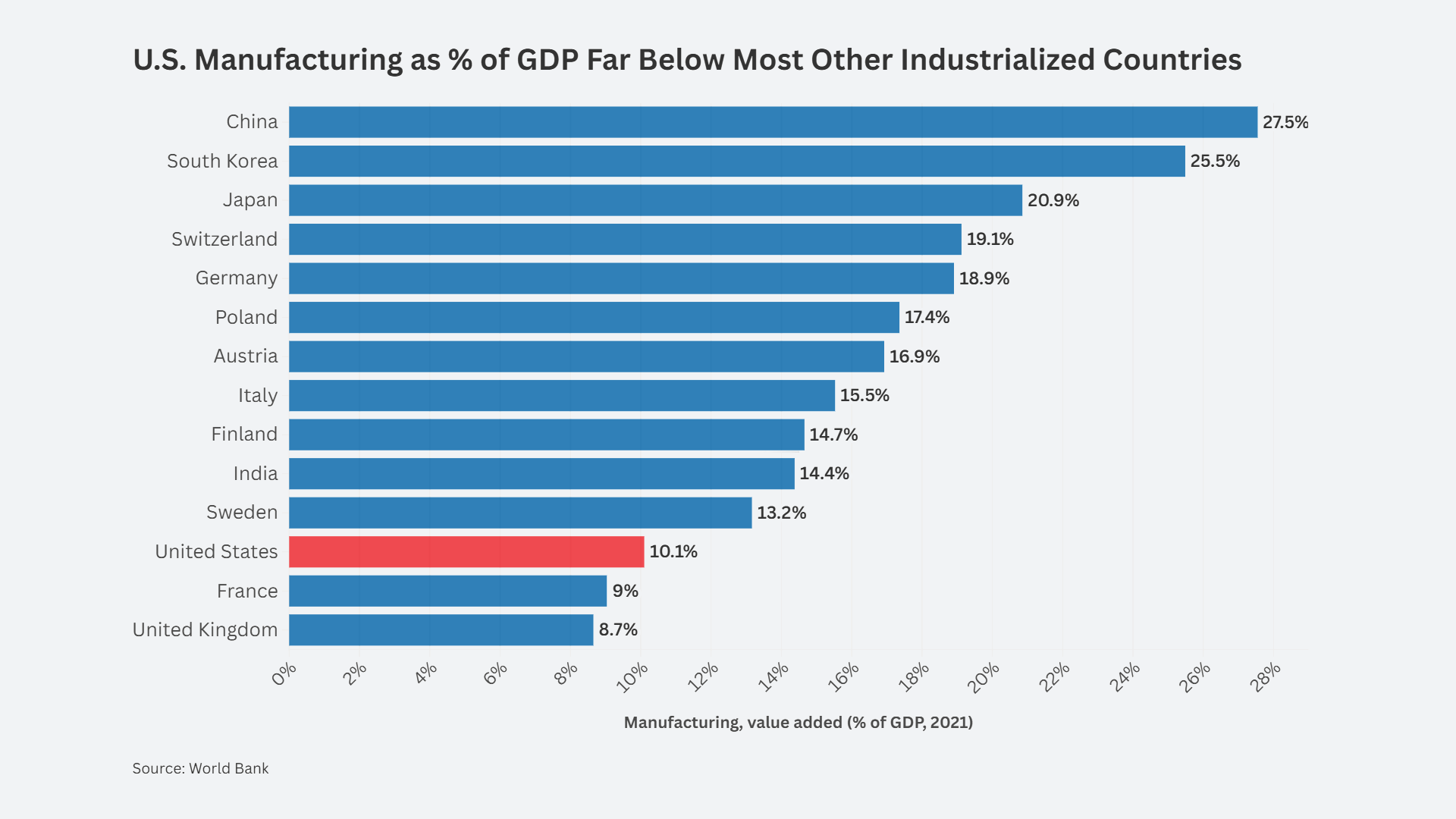

U.S. objections implicitly concede two points: first, that the national identity of world-leading companies and research institutions, along with their employees, matters significantly for both security and economics; and second, that Chinese industrial policy is likely to succeed in tilting the balance toward Beijing. Yet if these premises hold, then China’s use of industrial policy is wise, and Washington’s refusal to adopt a comparable approach is foolish.

China’s recent launch of a second state-funded semiconductor development fund valued at $29 billion, following an earlier $20 billion fund for the same purpose, prompted a former U.S. assistant trade representative to complain that “China is doubling-down on the state-led practices and policies that led to the trade war.” But China’s strategy resembles what Mariana Mazzucato, economist at University College London, calls the “entrepreneurial state.” Her 2013 bookchronicles how state investments were crucial in fostering industries that the U.S. still leads, such as IT, biotech and fracking.

Renewing this approach in the U.S. will require conservatives to set aside their aversion to government intervention. Liberals may need to accept lower social spending to pay for industrial policies that could be seen as “corporate welfare.” As Bloomberg Opinion’s Noah Smith has pointed out, the bad press generated by the failure of solar energy startup Solyndra, which received subsidized government loans from Barack Obama’s 2009 stimulus plan, has made such aid politically toxic. Yet failures will inevitably occur, even when industrial policies are properly designed and implemented.

A congressional advisory panel on artificial intelligence, chaired by ex-Google Chief Executive Officer Eric Schmidt, recently recommended that the U.S. government “partner with the commercial sector” to help overcome substantial technical and financial barriers to AI research. Whatever its flaws, the Green New Deal is also based on an acknowledgement that relying exclusively on free markets is insufficient to achieve important national objectives.

A world in which two superpowers both plow money into advanced research and development is hardly a dystopian vision. On the contrary, the result could be faster productivity growth in both the U.S. and China. And assuming the harshest scenarios for U.S.-China “decoupling” don’t come to pass and technology supply chains remain globally integrated, the benefits of subsidies would be shared by end-users around the world.

Read the original article here.